A Chorus Line opened on Broadway July 25, 1975. When it closed in 1990, the "little musical about chorus dancers" had become the longest-running show ever on Broadway (a record which would be surpassed by Cats in 1997). The musical phenomenon, which pulled back the curtain on the struggles and triumphs of Broadway dancers, has since inspired generations of performers. On the occasion of its 50th anniversary, Playbill is republishing this essay from 1983, when co-book writer James Kirkwood reflected on the show's impact. Kirkwood would pass away in 1989 of AIDS-related complications, two years after the death of show creator Michael Bennett and show lyricist Edward Kleban—Kirkwood's co-book writer, Nicholas Dante, would die of AIDS in 1991, another signal of how the disease took away a generation of musical theatre talent. A Chorus Line lives on in their memory.

Someone asked me the other day if I ever imagined coauthoring the longest running show in Broadway history. I never imagined coauthoring the shortest running show in Broadway history. I had always imagined being on the other side of the footlights and was for all of my younger years.

I began writing, oddly enough, because I fell in love with an electric typewriter while playing the "son" of "Valiant Lady" on the now defunct soap opera of the same name. The machine belonged to the writer of the soap; it was an imposing blue monster of an IBM, and I asked permission once to try it out. Knocking off a brief letter, I was so impressed by the heft of the thing and its raw striking power that, although I had no idea of becoming a writer, I zipped out a few days later and plunked down five hundred and some dollars for one of my own. (Yes, and it seemed like a fortune then; remember, this was pre-almost-everything.)

The soap opera soon went off the air and, as most of television had moved to California, I cried "Westward Ho!" and set off to make my fortune, either on the large silver screen or the somewhat smaller one that fits in people's homes.

Well, I wasn't going to leave a typewriter that cost that much out on the street with an old mattress, a lamp, and some unused kitty litter, so I lugged it out to la-la-land, where the sun always shines and where one elderly writer once quipped: "The last time I felt anything in California was five years ago when I was hit by a car crossing Sunset Boulevard."

Lap dissolve—as they say in The Industry—to years later, by which time I'd returned to New York with several books and a couple plays behind me. Same typewriter. I had written a play entitled P.S. Your Cat Is Dead! Michael Bennett was suggested as a possible director, and we met several times to discuss the project. Michael finally decided against it; Michael is intuitively bright; P.S. is not even on the list for Longest Running Show in Broadway history.

Another Lap dissolve: 10 months later, a theatre lobby during intermission and there stood Michael Bennett, who, upon seeing me, snapped his fingers and said, "Hi, Jim, I've been thinking about you lately. Have you ever thought about writing a musical?" I said I'd given the matter thought, but I had no idea how to go about doing it. He said apparently nobody had a foolproof recipe or people would be turning them out left and right and suggested we meet the next day and talk about the idea he had.

When Michael told me he wanted to do a show about chorus dancers auditioning for a Broadway musical, what they have to go through and they they go through it—I was hooked. Having been over the obstacle course many times myself, I knew auditions ranked right up there in brutality with the Spanish Inquisition. I also realized, by that time, that performers are among the bravest creatures walking the earth, that the stamina it takes to withstand rejection on such a personal level for one's entire professional career makes "being in the theatre" about as easy as swimming the English Channel against the tide. And let's not forget about the sharks. I felt the essence of the show in my guts and signed on immediately, joining Michael, Bob Avian, Marvin Hamlisch, Ed Kleban, and coauthor, Nicholas Dante, to prepare a workshop production of "this little musical about chorus dancers" as it was known (or mostly unknown) then.

Was it happy collaboration? For me, an unqualified yes. Nicholas was a joy to work with; our main quarrel was over punctuation. That's a happy collaboration, believe me. I believe it was happy for everyone, precisely because it was about our business, show business; we were writing close to home.

For warm-ups, Michael arranged meetings with various dancers with whom he'd conducted rap sessions so we could inhale the essence of their earliest drives, their later ambitions and dreams, their humor and every day philosophy of existence in the theatre. Soon the creative team assembled daily at Michael's apartment and played "What if?" "What if there's a dancer who has stopped a few shows in featured spots, but is now down on her luck and back auditioning for the chorus?" "What if she and the director had lived together years before and now they meet again on another level?" "What if there's a boy who thinks he can charm his way through the audition by making jokes?"

Playing "What if?" can be fun and exhilarating; it can produce spinoffs you never imagined when you began the game, which is not a game at all; it's deadly earnest work but best called "a game" so you don't freeze creatively.

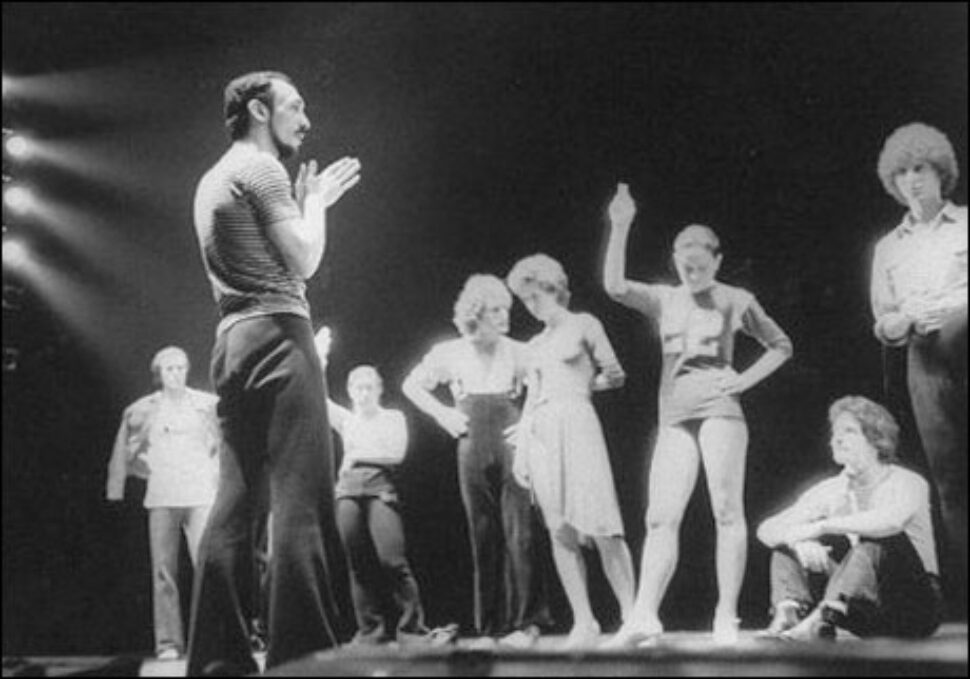

Soon we were meeting at a rehearsal studio down on West 19th Street with all these talented hand-picked dancers who finally realized they could not only dance and sing but, yes, they could talk, too. And they were so good at it, we kept writing things for them to say and all this talk, combined with Marvin and Ed's appropriately compelling music and lyrics, together with incredible choreography, produced a four hour and 20 minute run-through the first time we put all our ducks in a row.

Shock. Four hours and 20 minutes! Over twice the show we needed. I asked Kelly Bishop (Sheila) what she thought and, dripping wet from the marathon ordeal, she sighed: "Honey, we got War and Peace meets Ben Hur as a musical."

Back to Michael's apartment. Order deli; pastrami all around. Reorganizing began, entire subplots bit the dust. Here's where master game-plans and foresight come in. From the beginning, Michael planned building the show low-key with no harsh spotlight focused upon us during construction. Had we been going the usual route (Boston, Philly, etc.), we could have achieved nothing more from night to night, what with paying customers to please, than cosmetic surgery, applying a Band Aid here, taking a snip or a tuck there. Knowing we were only returning to West 19th Street with no audience to please but ourselves, we could perform major surgery without benefit of press or public scrutiny. And this was done under Michael's captaincy: honing, refining, drilling the troops until the performers were virtually over-rehearsed. Like race horses in the starting gate, they bridled to try their legs, to feel the response of an audience, any audience.

Finally, on a Sunday afternoon in early April 1975, an invited group of no more than 45 people, including Joe Papp, who'd given us free rein, and Bernie Gersten, our daily father-figure, straggled into the Newman Theater down at the Public for a stumble-through. Even with such a small group, electricity filled the air; it was tangible; something special was taking place. Yes, but there were those who wondered if it might be too special. Would the problems of chorus dancers auditioning for a Broadway show be universal enough to grab a lay-audience, would they care?

We prayed to God they would. We did, but we were in and of the theatre; the dancers were a projection of our lives, as well, up on that stage. A theatrical person's credo, which is to say: love me, appreciate my talent, give me a chance to come through, choose me, use me.

Now Robin Wagner (sets), Tharon Musser (lighting), Theoni V. Aldredge (costumes), Donald Pippin (conductor) were in active attendance, working their magic, as we officially moved into the Public for more fine tuning. By this time the cast was being put through the equivalent of Marine Boot Camp.

Was it all going that smoothly? No. several performers had gone AWOL earlier, thinking there was no future in this show. Our original Zach had left "due to artistic differences," and Robert LuPone had stepped up from the part of Al. Rumors filtered down that there were those at the Public who feared there was a ticking bomb about not to go off. Nerves kicked up as much as the performers in the finale.

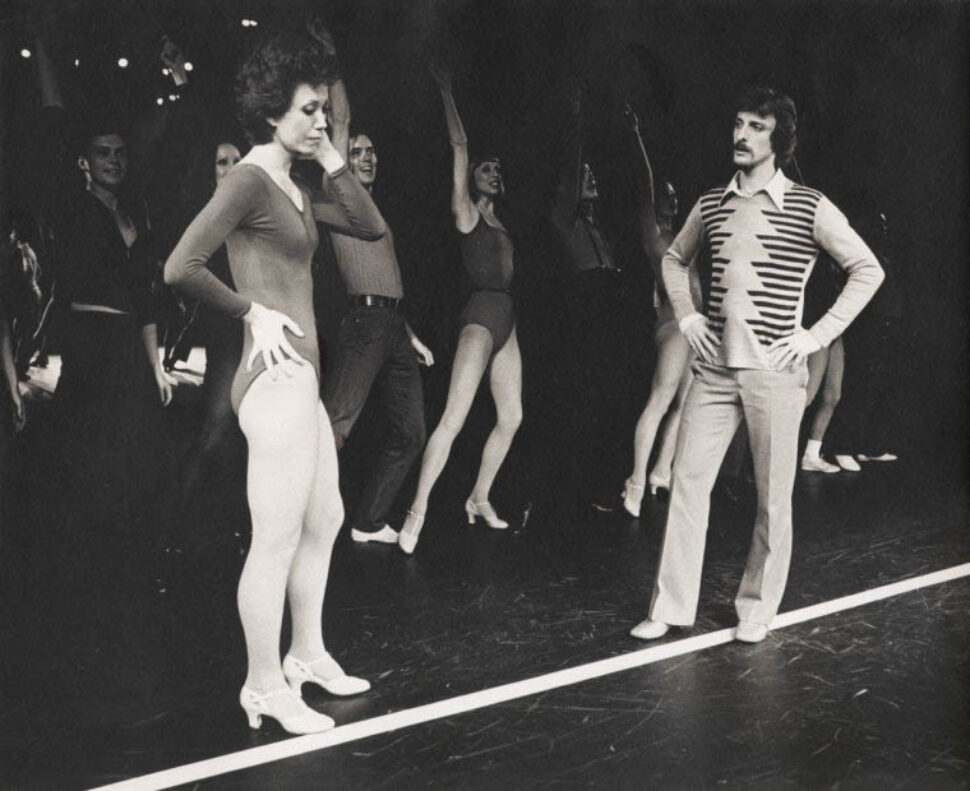

Then, on the tremulous night of April 16, 1975, we gave our first public preview. The show took off; the cast was airborne; adrenaline bounced back and forth from stage to audience. Donna McKechnie stopped the show; so did a few others. Those underground drums started beating. Suddenly traffic below 14th Street picked up as theatre people began trooping down to Lafayette Street to see exactly what was going on with "this little musical about chorus dancers." Tickets were gobbled up; phones were ringing; signs were optimistic. Still, no one was eager to rush headlong into any fray. We previewed, rehearsed, took and gave notes, changed, spit, polished, and nit-picked until our official opening night press unveiling on May 21st.

A strange and magical night for all. Because the Newman is such a small house and the demand for tickets was so strong, the creative team did not attend in the flesh. Dressed in our dinner clothes, we nervously gulped champagne, downed tranquilizers or anything else we could lay hands on and listened to the show which Joe Papp had piped through into the neighboring theatre, called The Other Stage. Every so often, one of us would be dispatched to streak over and peek through the back door of the Newman for visual confirmation of the reaction we could hear over the PA system. The response was as much as anyone could have hoped for, followed by a standing ovation. Around midnight the reviews began pouring in. The show worked; not only did people care; critics cared. Oh, how we partied the night away. What a glorious feeling to stumble home, squinting against the rays of the rising sun, praying for aspirin and vitamins, secure in the knowledge that all those months of work were appreciated.

Still, there were some who said the show worked exactly because it was housed in an intimate space but—watch out for a big Broadway house! Well, we watched out for the Shubert Theatre, and the Shubert has been watching out for us ever since, enough to garner 9 Tony Awards, a Pulitzer Prize, and many other tributes in 1976 alone. In the winter of that same year, two new companies of ACL went into rehearsal simultaneously at the City Center. The sight of legions of dancers galloping through their rigorous paces is a testament to the construction of that venerable building. I mean, those floors were vibrating.

Again, there were those who said the show was indigenous to New York City, to Broadway itself, and would not travel. Again, "they" were mistaken. The show had legs, traveling in time to Toronto, London, Australia, Japan, Mexico City, Argentina, Brazil, Sweden, and, of course, almost every playable city in the United States.

At this date, 457 performers have danced ACL in this country alone; 920 people have been employed by the show. When one thinks of the worldwide total, the legs and mind wobble. Now, when attending a new musical, you will find it almost impossible to read the "Who's Who'" in Playbill without finding two or three dancers who have appeared in some company of ACL, whether they're disguised as Cats or 42nd Street hoofers.

.jpg)

How does all this feel? Absolutely terrific, amazing, unbelievable that nine years, which represents a certain hunk of one's life, has gone by with that lightbulb marquee flashing around the front of the Shubert Theatre announcing A Chorus Line on the inside.

How will it feel when it's no longer there? A trifle ghostly, a void, a small sadness because a certain hunk of one's life will be missing. How's it been, seeing it again and again with different casts in different theatres in different cities? I don't think there has ever been a time when, during the opening dance combinations, the tiny hairs on my arms and along my spine haven't stood erect in honor of the pure raw energy of the actor-dancers upholding the tradition and discipline of the theatre, which, despite its status of "chronic invalid," will always flourish. It continues to exist because there is no excitement to equal being in the immediate presence of live and lively performers, of experiencing their moment-to-moment talent and their fervent desire to transport an audience out of this world. And, indeed, to free many of its members from the burden of their daily existence, if only for a few hours.

Oh-oh, here come the flags: God Bless the living theatre and a million thanks for the great luck to have been a part of A Chorus Line.

.jpg)