A journey into the world of Jerome Robbin's Broadway is more than just a trip down memory lane. It is a chance to rediscover the brilliance, the wit and the poetry of one of the most inventive and influential artists in Broadway history.

Between 1944 and 1964 Jerome Robbins choreographed and/or directed 15 musicals and show-doctored another five. Beginning with On the Town and continuing through such memorable works as The King and I, West Side Story, Gypsy and Fiddler on the Roof, Robbins's unerring sense of movement did more than entertain. it helped define character, express emotion and enhance the text, so that dance no longer stood apart from the words and music, but became very much a part of the show's development. Take the dance sequences out of West Side Story — which Robbins conceived, choreographed and directed — and there would be no West Side Story. The landmark 1957 show was staged with a fluidity of movement that imbued the entire piece, extending the possibilities of dance and galvanizing musical theatre.

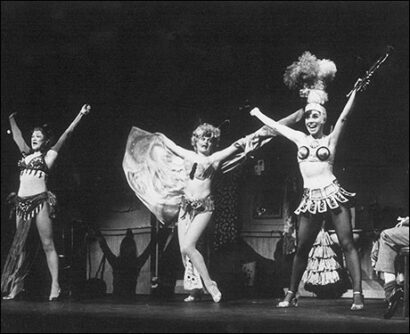

Robbins, who has devoted most of his career to the ballet stage, returns to Broadway for the first time in 25 years with a retrospective culled from roughly half the shows to which he contributed. Performed by a cast of 62 — yes, 62! — and 28 musicians, Jerome Robbins' Broadway features familiar numbers like "I'm Flying" (Peter Pan); "Comedy Tonight" (A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum); "You Gotta Gave a Gimmick" (Gypsy); and "The Small House of Uncle Thomas" (The King and I); and such lesser known gems as "Charleston" and "Dreams Come True" (Billion Dollar Baby); "I Still Get Jealous" and the legendary Mack Sennett-inspired ballet "On a Sunday By the Sea" (High Button Shoes); and "Mr. Monotony," which was cut from both Miss Liberty and Call Me Madam and has never before been seen in New York. Robbins has also put together specially arranged segments from On the Town, Fiddler on the Roof and West Side Story, which capture the essence of each of those works.

In addition to celebrating Robbins' contributions to Broadway, the show is a tribute to the composers, lyricists, writers and designers with whom he has worked. Thanks to their joint efforts, every number plays like a self-contained vignette. In "Charleston," for instance, Robbins created a gallery of instantly recognizable characters, even though each dancer is basically performing that one step. Yet the choreography is so precise, the movement is so pointed, that when it is combined with Morton Gould's music, Oliver Smith's set and Irene Sharaff's costumes, the intention of the piece is clear. "He has an incredible eye for truth," asserts Luis Perez, who figures prominently in two numbers. "Almost all the pieces in this show are about a specific community. Fiddler is a community. West Side is a community. Even 'Charleston' is a community. In each instance the audience is being asked into a well-defined world. And one of the things Jerry insists on is that we don't try to sell ourselves, that we don't throw these worlds out to the audience. Because then that world is destroyed. The audience must come to us — the audience must want to come to us."

In order for the audience to believe it is watching a community, it's essential that the dancers create that atmosphere. According to Victor Castelli, a soloist with the New York City Ballet who is serving as an assistant to Robbins on the show, the director relentlessly reinforced that point throughout rehearsals.

"When we were working on West Side, he plastered the walls with news articles about gang wars from the fifties," relates Castelli, "so that the kids would come in and read them and get the feel of what it was like. He did that with each number—he saturated us with material about the Charleston, or whatever. And before we started each number, he'd sit us down and explain what it was about, the show it came from, and where it came from in the show.

"In West Side he also had the dancers make up characters and relationships," Castelli continues. "He said to every person in that number, 'Make up a story — I don't care what it is. Why are you in the streets? What do your parents do?' It was important that each of them had their reasons for being in the Jets or the Sharks. Before the number, the Jets would form a group on one side and the Sharks would form a group on the other, and each would have its own pep rally. So by the time they'd get onstage they'd already have that tension between them. That's hard to do in this show, because you're constantly switching gears."

Given the vast territory covered in Jerome Robbins' Broadway, the many styles that had to be assimilated by dancers unfamiliar with much of the material, and Robbins's meticulousness, the musical had an unusually long rehearsal period of 22 weeks. Preparation actually began long before that, with Robbins contacting original cast members from various musicals to help jar his memory on numbers that had not been seen in years and had not been filmed or notated. He then went to work with a group of dancers and began reconstructing the various pieces.

"It's amazing how much Jerry remembered," says Castelli. "And where he didn't remember the exact steps, he remembered what the number was about, the feeling and the intent."

Dances from The King and I, Fiddler and West Side Story — shows which had been made into movies — were not particularly troublesome to put together. "Charleston" was once performed on a television special, and Robbins possessed a recording of it. "It was a bad film, but a film," says Castelli. Many of the other numbers were far more difficult to reassemble.

The Mack Sennett ballet, regarded by many as the funniest dance number ever created for Brodaway, turned up on a film that had been made from the front of the house, without Robbins's knowledge. "It was shot in 1947 with a hand-cranked camera," relates Jason Alexander, the show's narrator and guide. "It's in triple-fast speed, and some of the ballet is missing, but after watching it for a month Jerry used it as a basis to re-create the ballet. And it truthfully is hilarious."

Certainly the least known number in the show is "Mr. Monotony," written by Irving Berlin, sung by Debbie Shapiro and danced by Luis Perez, Jane Lanier and Robert LaFosse. In spite of the fact that "Mr. Monotony" was cut from two shows, the material is first-rate.

"The dance has been through about 25 different versions," claims Lanier. "Luis and I worked with Jerry last spring to help re-create it. He remembered parts of it, and then he kept trying things until he thought it was close to the original version. After he worked it out, Allyn Ann McLerie, who had performed the number originally, came in to look at it. She got up and danced, and she was great."

One of the high points for the entire company was when performers from the original casts came to rehearsals to look at the numbers and offer suggestions, corrections or approval. Betty Comden, Adolph Green, Nancy Walker and Chris Alexander helped out with "Ya Got Me" from On the Town. Mary Martin, the original Peter Pan, watched a rehearsal and was moved to tears. Yuriko, the noted Martha Graham dancer who appeared in "The Small House of Uncle Thomas," came in and fine-tuned the number. Helen Gallagher and several other members of the original cast of High Button Shoes checked out the Mack Sennett ballet.

Robbins also received input from the composers and writers whose material is used in the show. "It's like being a part of American history," says Perez. "We had a showing one time that was sort of a who's who of American musical theatre. Leonard Bernstein and Stephen Sondheim were there. Watching them watch us was a great thrill."

Music director Paul Gemignani recalls that Bernstein was invited to a rehearsal after the cuts and transitions were made for On the Town and West Side Story segments. "With few exceptions, he thought everything was absolutely right," says Gemignani. "And when he disagreed with something, he'd sit at the piano and say, 'Maybe we could do this instead,' and he'd write two bars of new music on the spot. All the writers and composers were helpful and enthusiastic. What's fabulous about Jerry is that he not only cares about what the music sounds like, but he understands music. You get notes from him saying, 'I don't know how to fix this, but the music sounds too dry.' Usually, the only criticism from directors is that the orchestra sounds too loud."

The show retains the original orchestrations for each song whenever possible, so that the moment you hear the music a particular period is evoked. But even though every aspect of the show has been re-created as faithfully as possible, the performers contend that the dances do not look quite the same as they did originally. The dancers are portraying the various styles, rather than actually embodying them.

"Dancers move differently today," explains Lanier. "Everything progresses and changes. It's not just that dancers are technically better today, but that men and women see themselves differently. Society influences the way we dance. When Allyn Ann McLerie saw the way we perform 'Mr. Monotony,' she told us that we do it a lot sexier than it originally was."

The show has been a learning experience for everyone involved. "Watching Jerry work has taught me about simplicity," says Perez. "It's taught me that there is more than one way to do things, and that you should try them all before you decide. His love of theatre and his commitment are total. Watching him take his own work and pare away the parts that aren't essential for this show is a lesson in theatre craft. He understands what is necessary to make a scene work."

Just how well the scenes work is evident from the response on both sides of the footlights. The show resonated with emotion for the performers and the audience. "When we did run-throughs of Fiddler, we'd look at Jerry at the end and there would be tears streaming down his face," recalls Castelli. "You didn't need a compliment after that."

Adds Lanier, "We have some special performances of the show in Purchase, NY, and I went out front to watch West Side. I had to leave before they got to 'Somewhere' because I always cry during that part, and I didn't want my stage makeup to run. Can you imagine what it must have been like to be in the audience in '57 and see those dances for the first time!"

"He changed musical theatre singlehandedly," asserts Jason Alexander. "When you see stuff like this, you can no longer be totally satisfied with dances that are just for dance's sake, with dances that don't move a story forward. And this show has aroused emotional reactions like nothing I've ever been in. When the curtain goes up and the audience sees 60 people take the stage and bow, the place goes nuts — and we haven't done a thing. It's an incredible feeling."