*

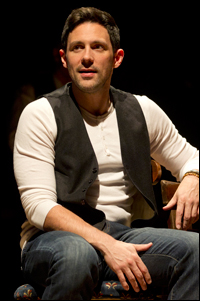

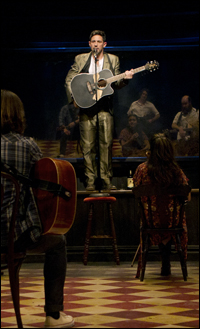

Kazee appeared as the absurd Sir Lancelot in Spamalot and was the swaggering Starbuck to Audra McDonald's Lizzie in the musical 110 in the Shade, both extroverted roles. As Guy, the Irish busker and songwriter in Once, based on the indie film, he's a brokenhearted and stuck artist whose fears threaten to drown him. And then a Czech-immigrant muse (known only as Girl, played by Cristin Milioti) inspires him to play on — in a club, in a record studio, in life.

Maybe you need to play a broken soul in order to truly explode on stage? Or maybe director John Tiffany's spare staging on a multipurpose Irish pub setting forces us to focus on the characters and actors in deeper ways than we might elsewhere? Or maybe it's Kazee's passion for folk and country music — styles closely associated with Glen Hasard and Marketa Irglova's folk-pop score of Once — that make him so rooted, authentic and passionate in the part? Whatever the answer, Steve Kazee is breaking out as never before in one of the season's must-see performances. We spoke to him during previews prior to the show's March 18 opening.

In a company of actor-musicians, you play guitar so confidently and beautifully. Are you a natural musician or is this something you had to grow into for Once?

Steve Kazee: I never really trained to be a musician, but I've been playing guitar since I was around, like, 13 years old. For me, the guitar has always been the instrument that I've played. I play a little piano. I taught myself everything by ear. I don't read music at all, which has not really been a hindrance. I've gotten this far without reading music, so I just learn everything by ear and by watching other people, and that's been the way that I've operated as a musician.

Were you playing guitar every week, even before Once?

SK: Oh, yeah. I played all the time. For me, music is sort of my passion, more so than being an actor. I just never tried to make a career as a musician. It was just something that I did on my own time, just for me. I had written a lot of songs, but I don't really record a lot of music because, for me, it's the same way as a poet: I write to get things out. It's sort of cathartic. Music has always been just for me. This is the first time that playing an instrument has really been for other people. Did you have a garage band as a kid?

SK: Oh, no. It was mostly just for me, in my house, in my bedroom. I just liked music. I've always loved music, so I liked playing music, but never really had much desire to make a career out of it.

It sounds like you can sort of really tap into what Guy is going through — sitting in his bedroom, noodling and creating stuff.

SK: Yeah, absolutely. No doubt. There's a lot of things about this character that I can really sort of grasp onto.

Are you attracted to the sort of folk-ballad music that populates Once?

SK: Yeah. Well, I'm from Kentucky, originally — the eastern portion of Kentucky, which is the foothills of Appalachia. That is the music there. It's very folk. It's very county. It's ballad-y. A lot of storytelling. The same sort of instruments that we use in the show — the banjo, guitar, mandolin, the violin, which we call the fiddle — all those instruments are very much a part of my growing up, so it's a very familiar territory for me.

| |

|

|

| Kazee in Once. | ||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

SK: It's Ashland, KY.

That's where you attended high school?

SK: Yeah, a little school called Fairview.

Did your family listen to country music and bluegrass?

SK: Yeah. Well, my dad does. My mom is more of a classic-rock enthusiast. She sort of turned me on, at an early age, to the Doors and Pink Floyd and Steppenwolf and a lot of different bands like that. My dad was the other side, which was like the George Joneses and the Patsy Clines, the Merle Haggards — that sort of world, which I think is where a lot of my musical infusion takes place. Today I'm a fan of bands like Mumford & Sons and a guy by the name of The Tallest Man on Earth. It sort of just blends both of those worlds so beautifully.

| |

|

|

| Cristin Milioti and Steve Kazee in Once. | ||

| Photo by Joan Marcus |

SK: No. It didn't happen until much later for me. I grew up in a very small, rural country town, and we didn't really have "the arts." What's amazing is that, nowadays there, the arts have grown and blossomed. They have a new multimillion-dollar theatre complex and everything, but all that stuff was put in place way after I left. So, for me, I didn't get involved in theatre until college.

Where was that?

SK: Morehead State University in Kentucky. I had been in choir the last couple years of high school because I always liked to sing and everything, but I never really thought of being an actor. I was in college, and I walked a girl that I was seeing at the time to an audition, and I got asked if I wanted to audition. It was for a musical. It was for Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat. I went in, and they asked me to sing something. I didn't really know what to sing, so they just had me sing "Happy Birthday." I got a callback from that, and then they had me sing "Benjamin Calypso," which was hilarious. [Laughs.] And I ended up getting cast as one of the brothers in Joseph.

And that was the first acting thing for you? At Morehead?

SK: Yeah, at Morehead. That was the beginning of all of this, which is so strange to think about.

Did it seem instant to you — the comfort of being on stage?

SK: Yeah. I had tried so many different routes and professions and jobs and different things that I wanted to do in my life, and I never really found anything that roped me in, and this was the first thing where I just felt at home. And I hear a lot of people in this business, they talk about that. They talk about finding a home, and, for me, I felt like I just finally found the family that I belonged to. That was in 1995, '96? So we're going on almost 20 years now.

When did you get to New York?

SK: I got to New York in 2002. I sort of had a really roundabout life. I went to college for two years, and then I dropped out for three and just sort of traveled around the country and worked at little community theatres — wherever I could get jobs that would pay enough. I worked some in Syracuse and in California — all these different places. Then, I finally went back home to Kentucky in 2000 and finished up my last two years of college there, and I got my degree in theatre. I had always been a big fish in that pond in Morehead, and I sort of wanted to see if I could branch out and do something a little bigger, so I applied to NYU's grad acting program and to Yale's graduate program. I got into NYU. I came here in 2002, graduated in 2005 and pretty much started working right away. I have been blessed to never have had a day-job right out of college.

| |

|

|

| Kazee in Once. | ||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

SK: I got my Equity card doing Seascape here at — Oh, no, actually I got my Equity card, I believe. Let me think about this. It was either for As You Like It in the park… I can't really remember, to be honest with you. Those two jobs came back to back. It was either Seascape at the Booth or As You Like It at the park — the same year, 2005.

You're lucky to have been so busy as to not remember.

SK: [Laughs.]

I'm curious to know what Once director John Tiffany is like in the room, when you're creating this character who has already been seen on film.

SK: I'm not sure that I can find sufficient words to describe what kind of a presence and a vast genius this man is. He has this simplicity about him, which he brings to his work, and a specificity, which sometimes you don't get in simplicity. He, along with [choreographer] Steven Hoggett — our whole creative team, really — those two, in particular, have a way of working together, which just fosters this air of creativity. You feel like magic is happening at all times, and you feel like, at any moment, the most magical thing can come out of nothing, which for me, as a sort of science and astrophysics nerd, is a really interesting idea — this idea of something out of nothing. Creating things out of thin air — the two of them are just amazing at doing it. But John has a focus and is able to really sort of laser-point and cut out precisely what he wants and present that to you in a way that is very easily digestible as an actor, and that gives you the opportunity to recreate that in front of an audience every night. I think it shows. I have never been lucky enough to be around this much talent and this much creativity. The word "genius" gets thrown around a lot, but this is the first time I've ever experienced what I can truly say is, I think, genius ability.

The film, the source material, is so delicate. Was it your instinct at the beginning of this process to be "bigger" — to be more "musical theatre"? Or was the delicacy always there?

SK: No, the delicacy was always there because I am very resistant to the idea of "musical theatre" as a style.

Resistant to Showbiz style.

SK: Showbiz, yeah. The lights and the big hands and the big smiles and the big movements and giant costumes and sets. I think those days — I'm not saying they're gone forever — but we're entering a new phase in the arts world where, I think, minimalism is making a comeback. I say that in the face of some giant shows like Spider-Man, but I do think that the trend that we're seeing over the last couple of years is that things have become sort of smaller. Cast sizes have dropped. Economically, they've dropped. When you see something like [the actor-driven] Peter and the Starcatcher, for instance, which has such a simplified idea to it, you leave that feeling so full. You know what I mean? I think that people are finding a way to really find life and broadness in the finer, small things in life — the delicate things in life. So, for me, it wasn't a problem. I just try to play honesty, always. And, honesty is not always broad. If you're playing a role that requires that, then sure, but this guy's not that. This guy is introverted, and the only way he can express himself is through music. So, for me, I didn't have any problems with that.

One of the things that seems to be built into this production is that Girl is much more of an active muse than she is in the film. That helps make it — not showbiz — but make it clearer or more focused, in a way.

SK: Well, you know, [librettist] Enda Walsh did a wonderful job of making this film, which is so small and intimate, theatrical, which is really a task. He found a way to make it theatrical without making it broad. I think a lot of the credit goes to him and his script and the work that he did, incorporating characters from the film that weren't as big as they are in our show and just finding a way to really balance that out. Speaking of another really sort of amazingly profound talent, if Enda Walsh isn't that, then I don't know what he is.

| |

|

|

| Kazee and Cristin Milioti in the recording studio. | ||

| Photo by Joseph Marzullo/WENN |

SK: Well, I know it through research only. I know it through heritage. Three-quarters of my family is Irish. Of course, the "Kazee" is not. For me, it was about just hanging out with a lot of people from Ireland. I spent a lot of time at a bar called the Scratcher, which is an Irish pub down in the village and hung out with a lot of Irish musicians and tried to get the grasp from Enda and from this guy Mark Geary, who's an Irish musician — friend of Glen Hansard's. Spending time with Glen and just sort of talking about Dublin and what's been going on there over the last couple of years, and doing my own research about [the Irish economic trend of ] the Celtic Tiger and how that affected everyone living there and how that brought the influx of the Czech people into Ireland, and now they're all sort of there with nothing to do.

It's strange: One thing that we never really get asked about is Dublin, itself. And I think that Dublin is actually one of the extra characters in our show. Even though the Guy is going to New York, and he is leaving Dublin, this story is still about how music affects a city, music affects people, music affects relationships… One of my favorite lines in the show, which never really gets referenced all that much, is at the very end. The banker says to the piano shop manager, he says, "You can't have a city without music," and I think that's a very profound thing to say, and I think it's a very true thing to say.

That idea becomes visual when the characters climb to a bluff and look down on the twinkling lights of Dublin. It's a breathtaking design.

SK: Bob Crowley, I tell ya!

Your relationship with songwriter Glen Hansard, who created this role on film, how would you characterize that? Has he been open about talking?

SK: Oh, yeah. Absolutely. Glen has been amazing. When he saw the show in Cambridge, when we did the workshop, I was very nervous. I'm a huge fan of the movie. I'm a huge fan of his. I will never be Glen Hansard, and I knew that from day one, so I chose to never even try to imitate that. And, he was very accepting of that. He was very willing to work with me and say, "Make this song your own. Find things in this song that you can relate to, to make it your own song." For an artist to do that, it's pretty rare — especially with something as personal as songwriting. But he has been an absolute gift to this production. He has been a gift to me, in my life. And, he's somebody I would consider a very good friend.

| |

|

|

| Kazee in Once. | ||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

SK: That would be true. [Laughs.]

You're standing a great deal.

SK: That is true as well.

Can we talk stamina? From an actor's physical point-of-view, you have an instrument in your hands and on your body — the guitar. Does your body have to grow into that?

SK: Well, it's ironic that you should ask on a day like today when I go to my physical therapist at 4:30! Yeah, I have once-a-week physical therapy. Carrying a guitar around your neck for two-and-a-half hours every night does something to the spine and the neck. Unfortunately, when you have to sing, as well, it causes you all kinds of problems, and it's not necessarily a light load that I'm singing either. It's not lilting melodies. It's pretty raw, heavy singing. I always feel, as an actor, your body is an instrument, so I have vocal lessons with Liz Caplan, which is brilliant and keeps me tuned that way. And then, I go to my physical therapy, which keeps me tuned that way. So, in a lot of ways, you're like an automobile — you have to go in for maintenance. I try to do it once a week. It keeps me sane. It keeps me healthy. I just do my best to always be at my top. But it's a learning process. And, the great thing is, I've basically been at this for a year now, so I'm sort of in the rhythm of this show. But where we had five or six weeks off, and we came right back into tech, there was definitely a readjusting process to that.

Do you ever get back to Kentucky?

SK: I do, occasionally. It's not as much as I would like, but I try to get back as often as possible because it keeps me sane. It keeps me remembering exactly who I am and where I'm from, so that when I see my picture on a billboard on 45th Street, I don't think I'm something special — and I remember that I'm just some kid that grew up poor in Kentucky, and that when I go home, I still go home to a trailer. So that's the way it goes!

Keeps you sane.

SK: Absolutely.

It's pronounced kuh-ZEE, right?

SK: It is.

Is it part Polish?

SK: It's Dutch, from what I've learned. Although, I was at Duane Reade two days ago and was told by the cashier there that it was actually Indian, but that it's spelled with a Q in India, and I said, "Well, I've never heard that before," so I don't know.

That's an unlikely heritage, possibly.

SK: Well, possible. You never know. Stranger things have happened.

(Kenneth Jones is managing editor of Playbill.com. Follow him on Twitter @PlaybillKenneth.)