*

This month, we ferret some facts from the fellas of Broadway's Follies, Ron Raines and Danny Burstein, the respective Ben and Buddy of James Goldman and Stephen Sondheim's groundbreaking 1971 musical. The Eric Schaeffer-directed revival is currently in previews leading to a Sept. 12 opening at the Marquis Theatre.

Warning: These interviews contains some plot spoilers, if you are new to Follies.

RAINES ON THE ROOF

Danny Burstein calls Ron Raines a cowboy, and the east Texas-born and raised Raines will channel Roy Rogers if you get him going about songs that feature Texas cities. I think he sang me four or five, ending with "The Streets of Laredo." The son of an evangelical minister, Raines says he sang before he ever spoke. "My mother said they just stood me up on the pew and I'd hold a songbook and haul off and sing."

A high school production of Oklahoma! gave him the bug and sent him to — where else? — Oklahoma City, where he got a degree in vocal music and made his way eventually to NYC (first Broadway show witnessed: Pippin), where a "left turn" led him into the world of soap operas as the villainous Alan Spaulding for 15 years on "Guiding Light," until the show ended in 2009.

Raines, reflecting on the demise of the soap, conjures a Sondheim lyric from "One More Kiss" in Follies: "All things beautiful must die," he said. "Everything dies." But out of death comes life, and Raines has given new life to Follies' Ben Stone, a character he originally played over 20 years ago. The show marks Raines' first on Broadway since a run in Chicago in 2002.

Congrats on your return to Broadway.

Thanks! It's going very well. I think there's been a lot of tweaking and improvements in the show that we weren't able to address [in the late-spring Washington, DC, run at the Kennedy Center]. When we got up here and were able to go back into rehearsal, they were addressed, and I think the show is going to be much better here in New York.

| |

|

|

| Raines and Bernadette Peters during the late-spring Kennedy Center run of Follies. | ||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

It's just better storytelling. Making the story clearer and clearer and moments clearer. It's just tweaking, you know? You just try to make it better. That's why you go into previews. We want to get it as right as we can. It's a tremendous group of people. And when I say a group, I mean quite a group. Forty-one people on stage. Lots of principals, and it's a great thing to be a part of. I'm very honored to be working with a lot of these people. When I hear the overture every night, it just blows me away. It sets the whole haunting tone of the evening.

This is a show that you have done as far back as '88.

Yeah, I did it in Detroit with Michigan Opera Theatre, with Nancy Dussault and Juliet Prowse, and our Carlotta was Edie Adams.

Wow, that's an exciting cast.

I was too young to do Ben at that time. Although I did a pretty good job, that character stayed with me. The role stays with you, and I remember saying, "I'm just too young to play this man. I don't understand him yet," but as I lived life, and life experiences came to me…I understood him more. He's a pretty messed up guy, but an interesting character.

It's rare, I would think, for an actor to play a character he's too young to understand, and then get to revisit it at an older age…

I remember I was playing Gaylord Ravenal in Show Boat when I was 32 in 1983 and I worked it with a guy named Allan Jones who did the 1936 movie of "Show Boat" with Paul Robeson and Helen Morgan…

Oh yeah, Allan Jones, father of Jack Jones.

Yeah, he'd done Show Boat all over the place. I remember him telling me the story. He said he went into the Players' Club and saw Dennis King. (Dennis King was another leading man in the '20s and '30s. He originated The Three Musketeers and The Vagabond King…he did the '32 revival of Show Boat.) Allan said, "Hey Dennis, we understand Ravenal now, but we're too old to play him!" I understand that as an actor. Sometimes as you finally start to understand a character, either no one is producing that show or you're not getting asked to do it. It's like, "Hey, now I'm ready!" but it doesn't happen. But, you know, Ravenal, unlike Ben Stone, starts at one age and ends at another age. So you're either the old guy or the young guy; that's a different set of problems. But the point is that, yes, for some strange reason when I was starting out in my career I was always playing older guys. I was playing fathers and I was going, "Hmm, a lot of these situations, I don't quite emotionally understand yet." But the characters stay with you forever. As life happens, you observe something or you experience something in your life, emotionally, and you say, "Aha! That's what the guy was going through."

Ben Stone is a guy who has some issues. Some self-delusion. How much can you relate to the harsher aspects of the character?

He's not at peace with the past. And the past that he's not at peace with has damaged his life. What happens, I think, at this reunion, that all gets stirred up. It's stuff that's been down there…[he's had] all these affairs and [he struggles with ] all this type-A overachiever, hungry-for-power-and-fame stuff… And yet, he wonders, what if he had taken another road. …One of the great songs, "The Road You Didn't Take," that's when he starts to crack a little bit — as he starts to regurgitate and talk about it to Sally. The beginning of the song starts one place but by the time it's over, some cracks in the façade are starting to show.

I think we all think, at some point, think of the roads we didn't take.

"What if I had changed my major when I really wanted to go into medicine, but I stayed in this business," and "What if I had gone into medicine?" "What if I had moved to Colorado that one summer?" Boy, I almost did it…but I didn't. A reunion stirs up everything. You can look back and it can be very regretful or you can look back and say, "Hey, I did all right. I got off the road a couple of times but I got back to my life and what I feel life is supposed to be about." This is a very grown-up show, yet it hits even younger people. I love talking about what their point of view is. I've had people tell me that they saw the original. They say "the original," and they were probably 25-30. It made an impression on them that has been everlasting, and they have seen many other productions of Follies. There are these amazing people out there that are Follies fanatics. They say how through the years it has hit them and affected them. It's a powerful show, and I think it does cross generations.

| |

|

|

| Raines and Bernadette Peters during the Kennedy Center run of Follies. | ||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

I took the right road.

I love it!

I got off the path a couple of times, but I got back on. And I don't mean that just in my career. I mean that in my personal life, too. I have a fabulous marriage to Dona D. Vaughn [artistic director of opera programs at Manhattan School of Music] and we have a fantastic daughter named Charlotte that we're just mad about. We live in the greatest city in the world. My wife and I have both made a living doing what we love to do. What more can one ask for?

That didn't come without a lot of work. That wonderful line that Phyllis says to Ben at the very end of the show: "Hope doesn't grow on trees and this will be the hardest thing we ever do." In other words, it won't be easy to repair that relationship of 30 years that's been so off base. And then Ben finally gets it at the end. He finally realizes his demons, and he's just stripped to the core and melts. The only way is up. It gives you that little light of thinking, "Maybe if they really work hard. If Ben is as determined to work on this relationship as he was to have that career, after losing everything else, there may be some hope."

| |

|

|

| Danny Burstein |

In the three-and-a-half weeks between the DC production at the Kennedy Center's Eisenhower Theater and rehearsals for Broadway, Danny Burstein took his sons Zach and Alex on a trip to a resort in the Bahamas while his wife, the radiant Rebecca Luker, was busy starring in Roundabout's Death Takes a Holiday (Off-Broadway through Sept. 4).

It was a nice break before returning to the stage, although Burstein does caution that a bottle of sunscreen at the hotel convenience store cost $56. Sunscreen is important, but that's money better put toward a ticket to Follies, methinks.

So, you got anything going on these days?

No, not really. You? [Laughs]

Well, there is this show, Follies. I've talked to you, in our past encounters, about your personal history, so I'd like to concentrate on your character in Follies, Buddy. How you are getting in touch with him?

I knew close to a year before we started production that they wanted me to do the show. I was thrilled at the very idea. I had never seen Follies and I still have never seen a production of the show. It was all going to be new and exciting to me. Of course I knew a lot of the songs, but then there was the other half of the score that I really didn't know. So they sent me the script, and I read it over and over and over and did as much research as I could about the time, about 1971 and 1941. Trying to figure the guy out and what he did. The sadness about the character and his trying to struggle out of that sadness. I ran into my buddy Evan Pappas, who had done Follies in London and played young Buddy. He turned to me as we finished the conversation — this was before I headed out to DC — he said to me before the door closed, "Don't forget that Buddy is basically a walking heart. He's all heart." And I thought, oh, a walking heart! It opened up a new way of thinking about the character for me in that simple phrase. I took it from there. Have you known Buddys in your life?

I hate to say it, but I have a lot to relate to it in my own life. Unfortunately. I don't wish that upon anybody. I mean that. I went through a difficult marriage. I have two genius, beautiful, remarkable kids to show for it. But yeah, I can relate to him in many ways. I've even said some of those, almost the exact same words.

Follies, populated by characters who are (or were) performers, deals a lot with that mixture of confidence and insecurity that is at the heart of a lot of performers.

Without a doubt, yes. I would say that at the heart of most performers. I remember my wife did a benefit years ago with Elaine Stritch. My wife was second-to-last to perform that night and Elaine was the last one to perform. The two of them were pacing around backstage and my wife said, "Even after all these years, I'm so nervous." Elaine, just as nervous, said to her, "I don't trust anybody who doesn't get nervous." If you don't have that struggle and the nerves and the adrenaline going through you every single night, then maybe you're in the wrong profession. It's part of the package and part of what makes people good because they are struggling with it every night to make it better and it still is exciting to them.

| |

|

|

| Burstein and Kiira Schmidt during the Kennedy Center run of Follies. | ||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

I'm glad I didn't. I'll be honest with you, I'm sure it would have been terrible. When I was 17, I think, or 16, I did Luther Billis [in South Pacific] in non-Equity summer stock, and I'm sure I was just terrible. I'm sure the same thing would have applied had I done Buddy Plummer when I was younger. I just never would have understood it. Two nights ago, [orchestrator] Jonathan Tunick and I were talking about the show and he said each person that sees this show at different points in their life will have different reactions to it every time. Seeing them and going, "Oh my God, those older people…" and then when you're middle-aged, "Oh my gosh, that's me." Then, he said, "Now that I'm 70, the youngest guy on the stage to me looks like Dimitri Weissman, the guy who runs the theatre." It's a wonderful show that way. It means something different to you at different points in your life.

And there's the original '71 production that everybody talks about with such reverence that it has a life of its own.

Absolutely. I have to always go back to the fact that freaking Stephen Sondheim was 40 years old when he wrote all this! You know? Wrote that score. How did he know? He was so prescient. He's a genius, there's nothing else you can say.

As a guy who has told me that you really wanted to do dramatic acting, is this kind of a beautiful hybrid for you in a way?

Without a doubt. Basically, what I'm going for, honestly, is the absence of acting. Just standing there talking on stage and letting the drama of the piece help make the rest happen. The fascinating thing about the process and finding it is that you're on stage for these short scenes and then you're gone for ten minutes. And then you're back on stage, but the drama has not stopped in between, in fact that drama has escalated. So you have to come in at a higher pitch each time. The intensity and your drive has to be even higher each time you come out, so you've got this crazy arc that you've got to stay on the entire night. I only knew that that arc was even possible or even there when we started doing run-throughs of the show. It was difficult. If you just rehearse the scenes by themselves, you don't have the same emotional fulfillment. You have to run it in order.

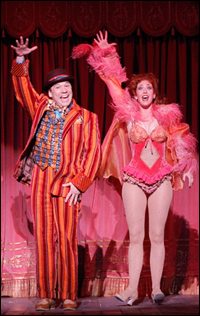

Your approach to "Buddy's Blues" shows Buddy's struggle both vocally and physically. How did you come up with that balance?

Well [choreographer] Warren Carlyle and I started working on the song and we knew the choreography had to stem from what was being said in the lyrics. We both had this great responsibility to make sure that the lyric got out and yet to personify the lyric in movement. He had this wonderful concept of it being a vaudeville sketch in a different way than [original co-director and choreographer] Michael Bennett's idea for it was. We just kept going along that line, feeling that it was… it was more burlesque than vaudeville. That's really what we pushed for, that feel.

There are little moments where the "walking heart's" anger is on display.

Those are the chinks in the armor, the cracks that people get to see, but only in a fleeting way up until the very end, where he loses it for a second and then finishes the song the way it's supposed to be finished. At first, I had this idea that he would leer at the audience and walk off very angry at everybody that he exposed himself that way. It just didn't work, so I thought if you can't do that and that doesn't work, why don't you see if you can break their hearts with it instead? All of the sudden, he finishes the song and can't believe that people are actually applauding, and it's a moment where he's forgotten all his worries in that one second, and then all of the sudden it all comes rushing back. The song is over and the moment is over and he has to go back to his life. With that in mind, we put that moment in at the end. It stayed since the very first preview in DC.

I'm curious how much you worked with your "ghost selves" and your "younger selves" during the rehearsal process. Are they working to imitate your body language?

Yeah we did a lot. Christian [Delcroix, Young Buddy] and I had a leg up because we knew each other and we're dear friends. I have such respect for him. In fact, I think he's one of the most talented people I've ever met in my life. I'm not just saying that. He can do anything. We have a great rapport already and many people say we favor each other. It's just ironic that we have the same sense of humor. We started to watch each other and started to take on the same mannerisms. So I feel like he and I had a much easier time than the others perhaps because we were so connected already.

In the past, you mentioned wanting to teach acting. I wonder if that's still something you're interested in and something you do?

Oh, sure. My wife and I both are invited to teach master classes here and there. Honestly, if ever there are opportunities to do that, we do it. It's very important for us to give back in so many ways. When I was an 18-year-old kid, I was doing Merrily We Roll Along at Queens College. I wrote Steve Sondheim a letter, and I said, "Look, I'm doing this show at Queens College." just a year or two after it closed on Broadway. I'm trying to figure out the character, I was playing Franklin Shepard. I had a zillion questions. He wrote me back and he said all these questions would have to be answered in a letter the size of "War and Peace." He said, "Here's my number, give me a call and we'll work out a time that we can get together and talk about this." And we did! I called him and I was so nervous, I went to his house and over a carafe of the best white wine I'd ever had, we talked for three hours about Merrily We Roll Along and several of his other shows. I got the most amazing lesson in musical theatre that anyone could ever get. That taught me a huge lesson. It was about giving back. Sondheim taught me that. It was a beautiful thing.

Would you prefer to always be able to meet with a creator and get what they're going for, or are there times you really just want to figure it out for yourself?

Honestly, people ask me all the time, what is that great role you want to play? What is the thing you've always wanted to do, be it Hamlet or…? But the truth is, I love doing new works the best. I find that the most exciting. I love being in the process. I want to be in the room with unbelievably smart, talented people that I can learn from. I want to gain something from the experience in that way. What were they thinking? I can't wait to work with a zillion writers that I could name right now. That's what I find the most exciting thing. They start to shape the character on you. It's remarkable. It's such a remarkable process and an honor that they chose you. It's like you work twice as hard to get it right. You make it new. That's exciting to me. I want to do something that's different every single time. I don't want people to go, "Oh that's exactly the same way he was in this other show." That's not what I want at all. I want it to be a whole new thing. I sort of pride myself on trying to do that.

Damn, is there nothing that's jaded about you?

Not when it comes to this stuff. I love it. I mean it. My wife and I just go out there every single night trying to do our best work. We come home, and it's like, "How was your show?" We talk about it. We're geeks that way I guess. We just love it.