*

Rob McClure was always told that he resembled silent film star Charlie Chaplin. It wasn't until he put on the tight coat, baggy pants, bowler hat, oversized shoes and tiny mustache — the iconic Chaplin attire — that he noticed the uncanny similarities. Now, following an out-of-town tryout of Christopher Curtis and Thomas Meehan's Charlie Chaplin musical at California's La Jolla Playhouse — as well as a turn in the title role of Where's Charley? for City Center Encores! — McClure returns to Chaplin for Broadway. (It's a job where the Broadway marquee indicates something rare: "Introducing Rob McClure.") In between rehearsals and "Chaplin Boot Camp" — consisting of roller-skating lessons, violin lessons, tightrope-walking lessons and voice lessons — we caught a few minutes with the show's leading man before Broadway performances begin Aug. 21 at the Barrymore Theatre.

Charlie Chaplin is an icon. Where did you begin to create him?

Rob McClure: My initial introduction to him was — this is a funny story… My Aunt Marian, my entire life growing up, told me that I looked like Charlie Chaplin. That didn't really resonate with me when I was younger — I hadn't seen a lot of his films. I knew of him, but I certainly didn't know anything in detail. When this show came around and the auditions were happening — she had passed away about six months before the audition... And, on my way to the final callback, her daughter called me and said, "Hey, we're going through her storage unit. Did you know that she painted a six-foot portrait of Charlie Chaplin? She always said you looked like him. Do you want it?" And, I said, "I'm going to a final callback for a Broadway[-bound] show about Charlie Chaplin," and I booked it. She gave me the painting, and now it's hanging in my house, so it was a strange sort of fateful coming together of moments. [Laughs.] Those [moments] have strangely been happening more and more. When I was doing [the national tour of] Avenue Q, and I left the tour, a card that [my castmate] gave me two years ago was a Charlie Chaplin card, and written on the bottom of it was, "Thank you for being a part of the tour. We'll miss you. I got you this card because you need to play Chaplin on Broadway some day."... Completely random! And, I found it after I had gotten the part and was in rehearsals. It's been a strange, fate-driven road to get here.

| |

|

|

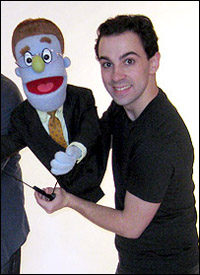

| Rob McClure and Avenue Q co-star Rod |

These ironic moments began to happen before you joined the production at La Jolla Playhouse?

RM: Yeah. I was doing a show at the American Repertory Theater in Boston, and I came [to New York] six Mondays in a row on my day off for another callback and another callback and another callback. [Laughs.] It was very funny, the final callback — I was in New York on a Monday at five o'clock, and I auditioned, and they said, "Okay, before you jump on your train tomorrow back to Boston, can you come in at 10 AM and have a two-minute Chaplin-y thing ready?" [Laughs.] I was like, "Oh my God, what does that mean?" So I panicked, and I went home, and I was in my bed at 2:30 in the morning, and my wife turned to me and said, "Well, why don't you at least bring music, so that you're not hung out to dry with the silence of the room?" And, I went, "Oh, that's good." So I started flipping through the classical music on my phone, and I had "Flight of the Bumblebee," and I thought, "Oh, okay. I'm going to play 'Flight of the Bumblebee.' I'm going to bring a fly swatter. I'm going to fight an invisible fly and lose." And, I fell asleep. And then I woke up in the morning, put my iPod in, got on the train, and people thought I was insane with a fly swatter and my iPod on, practicing [this idea] that I had come up with several hours before! [Laughs.] But the first time I did it full-out was in the room. I think it was in the right spirit of something that [Chaplin] would have come up with. And, I think that's important to the show — finding things that are specifically in his spirit. We don't want to just put his movies on stage because his movies are so special as films. [It's] finding the theatricality and finding the spirit of them, so that we can translate them into theatrical moments that are specifically Chaplin. Chaplin was quoted as saying that once he put on the mustache and the clothes, the character of the Tramp took over. Do you feel the same?

RM: Yeah, it's very interesting. With all these people saying, "You look like Charlie Chaplin," I never really thought [that] until they started putting the stuff on me. I was in the room, and I had the coat — the coat is too tight, and I feel it stretch across my chest — and I put on the pants, and I've got these huge, baggy pants and these gigantic shoes that don't fit, and then I got the hat on, and I'm going, "Wow, that's really close," and they put the freakin' mustache on me, and it kind of took my breath away. I thought, "Wow." It's kind of startling. I would definitely agree with that — no matter how much physical work I do — when the costume goes on, suddenly everything makes sense. What I think Chaplin was going for were the opposites — the huge shoes, the tiny hat, the big pants, the tight vest. Playing with opposites begins to define how and why he moves the way he moves. And, I can't help but feel that. It sort of informs the movement.

Did you ever study mime?

RM: No, I didn't. I've always been physical. I loved sports growing up. I was never specifically a dancer or anything like that. I certainly enjoy doing pantomime-y things, but I didn't have any specific training in it. And, what's interesting is that the subtlety with which he used... So many times we think of mime, and we think of these extraordinary facial expressions and these blatant uses of face and body to tell the plot, and there was nothing blatant about what he was doing. It's amazing that he was able to tell the amount of story he was able to tell silently without playing charades in front of us. Sometimes, when you watch those old Mack Sennett "Keystone" movies, people's performances depended on the size of their eyebrows and the size of their mustaches and doing these ridiculous huge expressions, and [Chaplin] came along and changed the game. For me, it's almost trying to achieve the same simplicity of playing a scene with contemporary dialogue, but finding that silently.

| |

|

|

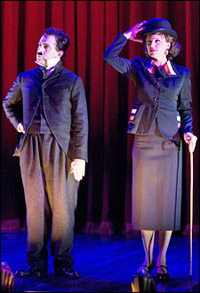

| McClure as Charlie Chaplin | ||

| Photo by Joan Marcus |

RM: [Laughs.] Yeah! When I was a kid, I was hugely impacted by "Jurassic Park." I think I was just the right age when that movie came out, and I remember running around my town like a Velociraptor. And, when you go in for an audition, it doesn't matter what you go in for — you can go in for Man of La Mancha — and you finish singing, and they say, "Great! Can you do your Velociraptor impression?" [Laughs.]

We studied at the same college — Montclair State University in New Jersey.

RM: No kidding?! Unfortunately, I didn't graduate. I was blessed to be doing Avenue Q and I'm Not Rappaport, but I part-timed a double major for as long as I could! [Laughs.] I would love to go back and finish someday, but luckily I've been blessed with work since then.

You also worked at New Jersey's Paper Mill Playhouse?

RM: I did. I actually feel like I owe a lot of my career — especially the beginning years — to Paper Mill. They have this really great program called the Rising Star Awards, which is like the Tony Awards for New Jersey high schools. I was doing theatre in high school, and they gave me the award in 2000 for Best Actor for Where's Charley? — which strangely I ended up playing at Encores! a season-and-a-half ago. So I won the Rising Star Award in 2000, and then they offered me a job in their mainstage production of Carousel, and that was my first Equity gig. The following season, they asked me if I wanted to do a cover in their production of I'm Not Rappaport, with Ben Vereen, which I thought was going to be a short gig. And, two weeks into that run, we found out that [the show] was [transferring] to Broadway, and that was my Broadway debut. I really do feel like I owe it to Paper Mill for my start.

| |

|

|

| McClure and Jenn Colella in the La Jolla Playhouse's world premiere | ||

| photo by Craig Schwartz |

RM: I think the show has a wonderful balance of drama to comedy… There are people who know everything there is to know about Charlie Chaplin, and there are people who — like I did when I first went into this — don't know much. His life was full of huge, massive ups and downs, which provides a really interesting night at the theatre. It was hugely poverty-stricken, so the audience gets to see the ultimate rags-to-riches story. He really does go from nothing to becoming the most famous man in the world, which is an amazing arc. But, what a lot of people don't know is that he had a pretty drastic fall from grace, too. There were some huge issues in his life towards his later years that were just fascinating. It's a beautiful, beautiful life, and, for me as an actor, to get to spend that kind of evening just feels epic. I do think that people come to a show about Charlie Chaplin expecting to laugh, and they will. We've got that covered. [Laughs.] But I don't think they'll expect to be as really, really moved. In previous incarnations of this show, I've had a lot of tearful faces at the stage door, who've come up to me and told me how much this story meant to them… I remember I walked out one day, and there was a 12-year-old boy at La Jolla who said, "I've never seen a Charlie Chaplin movie, but this was so great." The following Friday, he came back with ten of his friends, saying that this was his birthday party, and they rented ten Chaplin movies, and they're sleeping over for the weekend and having a Chaplin marathon. And, I welled up. The idea that I could be a small part of reintroducing this man to generations that might not be familiar with him is a huge honor for me.

How has Chaplin evolved since its run at La Jolla? I'm sure that you've been through changes for Broadway.

RM: Yeah. It's very different. [Director and choreographer] Warren Carlyle dreams big, and I'm so stoked for the New York audiences to see what he's dreamed up. Chaplin's life deserves this type of show. It deserves this type of storytelling on the scale that Warren's telling it… The design has largely changed. I'm so excited about what they're doing in terms of playing with color and texture and the cinematic nature of the show. There are moments where Warren is really combining the biographical, the cinematic and the theatrical. And, getting that balance right is so wonderful. Tell me about the choreography. Is it in the Chaplin vein? Is your staging choreographed as well?

RM: There are moments where Warren encourages freedom, but a lot of it is blocked within an inch of its life. Because Chaplin was so specific, getting those specifics down has largely shaped moments and [musical] numbers. The choreography — I think Warren, in the same spirit of Chaplin, has captured that balance of comedy and romance in the movement. There are moments where it gets very silly, and it finds that Chaplin charm — physically — and there are other moments where it's sweeping, sweeping romance. Not a lot of people know that Chaplin wrote the music for every one of his films. He was this incredible composer… A lot of people, when they think of Charlie Chaplin, they think of the rinky-dink piano stuff. Chaplin was not that. Chaplin had huge, sweeping orchestrations with strings. I think Chris Curtis' score largely captures that romantic, large sound.

| |

|

|

| McClure as Chaplin | ||

| Photo by Joan Marcus |

RM: It's something that I've played around with in the past. [Laughs.]… Growing up, I baked bagels. That was my job before going to high school every day. I loved doing theatre at night, so when it came time that I wanted to get a job, the only time that worked without having to stop doing theatre was before school. Being there alone until the first [customer] came, I would bake bagels and write stupid songs about a customer who annoyed me. [Laughs.]… Cut to six years later — I had just gotten out of college, and I went back to my old high school in New Milford, NJ, and I directed the musical there for a couple of years. And, my old high school woodshop teacher said, "You should do The Bagel Factory, The Musical." So we wrote The Bagel Factory, The Musical, and did this whole $33,000 world premiere. [Laughs.] It was thrilling! Any opportunity I get to flex those muscles again… If there's a little lull, I write when I can. I find that the more aspects of this craft I play with, the more I can appreciate. Believe it or not, directing at my old high school, I learned more about the spirit of collaboration there than I did anywhere else. When you have to make it happen at a high school, you're the director, choreographer, lighting designer, set designer, costumes… No one's paying you, but you have to make it work, so you do it. I've taken that with me into this realm.

What was your first brush with theatre? You grew up in New Jersey?

RM: Yeah, I grew up in northern New Jersey in a little town called New Milford. My first brush with theatre was when I auditioned for Bye Bye Birdie at my high school in eighth grade. I got in, but I turned it down because I was doing a statewide golf tournament and thought I was going to be a professional golfer — I had that wrong! [Laughs.] Before the following year's musical, someone said to me, "There's a little theatre called the Bergen County Players in Oradell, NJ, and they're doing this musical about a guy who kills people and puts them in meat pies." I was like 14 and thought, "That sounds like the coolest friggin' thing I've ever [heard of] in my life." So I went and I auditioned for Toby [in Sweeney Todd]. I said, "Hi, I'm auditioning for Toby" and proceeded to sing "Stars" from Les Miz. [Laughs.] If that's not a good gauge of where my theatrical sense was at that moment…! I had no idea what I was doing! So, obviously, I didn't get it, but I wanted to see this show, so I went back and I saw it. The moment that I found out it was [Sweeney's] wife at the end, I remember feeling so manipulated. I could not believe that I had fallen so hard for a story that was being told to me live. I was so invested in this story, [and] I remember thinking, "Tomorrow, there's going to be another hundred people here who don't know that's coming. I have to be here when they find out!" Every Friday, Saturday and Sunday for [the show's run], I rode my bike and spent $12 [to see] every performance of Sweeney Todd at the Bergen County Players. By the end, I wasn't watching the show anymore. I was watching the audience watch the show because that was what was fascinating to me… That became why I went every night — to watch people watch the show. I think that, specifically, is what "got me" about theatre. I can't do that when I'm watching a television show or when I'm at a movie theatre, [and] I don't get the same sort of journey. There was something about what was going on in that room. That was it. I was done.

How are you feeling at this point in rehearsals for Chaplin? Are you ready for Broadway?

RM: Rehearsals are going great. We're just chugging away. I take all of these crazy lessons. Every time there is a teeny-tiny rewrite, I'm taking a new lesson — like, "Hey, there's a new page, and you're taking violin lessons." [Laughs.] I'm now taking roller-skating lessons, violin lessons, tightrope-walking lessons and voice lessons in addition to the rehearsal time. That was "Chaplin Boot Camp." As I'm learning these things, I'm like, "God, this is a lot." Then I watch any of the hundreds of Chaplin films and think, "He did it. He did all of this stuff."

(Playbill staff writer Michael Gioia's work appears in the news, feature and video sections of Playbill.com. Write to him at [email protected].)