*

Vienna-born Jonas Sternberg (1894-1969) grew up in Lynbrook, NY, and New York City; dropped out of Jamaica High School; went to work as a menial in a Fort Lee, NJ movie studio; and served during the first World War as a photographer for the Signal Corps, stationed at Columbia University. Working as an assistant director in Hollywood in the early 1920s, a producer helpfully suggested that he change his credit from Jo Sternberg to Josef von Sternberg (in emulation of the already celebrated Erich von Stroheim).

Sternberg's silent "The Salvation Hunters," a moody piece filled with stunning visual composition, was what might be called an indy art house hit in 1925. Hollywood bigwigs Mary Pickford and Charles Chaplin, recently joined together with Douglas Fairbanks to form United Artists, proclaimed von Sternberg a genius and invited him to work for them. But the script von Sternberg devised for Pickford was so odd that she opted out. Chaplin, on the other hand, funded the 1926 "A Woman of the Sea" as a vehicle for Edna Purviance (who in her younger days had been his leading lady, on-screen and off). This was the only Chaplin-produced film that he neither starred in nor directed. Under circumstances that will presumably remain forever murky, Chaplin refused to release the finished film and appears to have had the prints and negatives destroyed. "A Woman of the Sea" is considered a masterpiece by some, although it was apparently screened only once and viewed by few.

This very public dumping by the great Chaplin seemed to place the fiery genius at a bad place, career-wise, but he managed to get a job as replacement director on the Paramount gangster melodrama, "Underworld." And the unheralded "Underworld" turned out to be a whirlwind success; it opened one August day in 1927 at the Paramount on Times Square. Word-of-mouth was so strong that audiences stormed the theatre following the final evening screening and demanded another, and then another, and then another; "Underworld" literally played through the night, with customers presumably slipping in from the local speakeasies. "Underworld" immediately established von Sternberg as a top director; that is, an unquestionably artistic filmmaker who could make films that the masses wanted to see. He continued in this vein at Paramount for a couple of years, after which he went to Germany to make "The Blue Angel," at which point he discovered Marlene Dietrich. Von Sternberg brought Dietrich back to America and embarked on a series of renowned films, earning a reputation as the stormiest German director this side of von Stroheim. But he was really Jo Sternberg from Lynbrook.

| |

|

|

Von Sternberg seemed adept at eliciting riveting performances, though, as evidenced by the second film in the set, "The Last Command" (1928). This one is altogether fascinating. Hollywood had a fair share of Russian emigres at the time, including an ex-general in the Czar's army who following the Revolution wound up running a restaurant in Hollywood. When the restaurant closed, he was reduced to looking for extra work at the studios. That served as the germ for "The Last Command," with the Czar's overbearing chief general (and cousin) transformed into a shell-shocked shell of a man and hired as an extra, assigned to play — what else? A Russian general in combat. With the director of the film in question being a former Russian revolutionary, who ten years earlier had been violently beaten by the very same general.

Standing out is the remarkable Emil Jannings. The flashbacks show him haughty and imperious (but with, again, a fascinating streak of humanity). The opening and closing display a shell of this same man; von Sternberg and Jannings manage to contrive two very different but very believable portraits of the same character. (The acting was such that I found myself impelled to immediately replay the final third of the movie twice, from the scene in which the general is arrested at the train station.) Jannings — two years before he went to Germany to make "The Blue Angel," inviting von Sternberg to direct him — won an Oscar for "The Last Command," and you can easily understand why. Jannings received the very first Oscar, literally; he was leaving Hollywood to make a film in Europe, so the Academy presented his statuette to him before the official ceremony.

Along with Jannings is Ms. Brent, perhaps twice as good as she is in "Underworld." Again, there are so many shadings to the character. The third major role — that of the Russian-born film director — is played by none other than William Powell, who here broke out of the second rank and earned a shot at stardom (which he attained the following year). The studio scenes, where Powell displays restraint and sympathy for the broken-down old man, are so very good.

| |

|

|

All three von Sternberg silents remain fascinating. Criterion has done their customary fine job of restoration, and the booklet is filled with interesting articles (including an excerpt from von Sternberg's autobiography "Fun in a Chinese Laundry" that reads so well that I want to find the book itself.) There are two musical soundtracks for each film; extras are few in number, but well worth watching. Anyone interested in early Hollywood, Dietrich or lighting will want to watch the 1968 Swedish television interview that is included. The 74-year-old director, just a year before his death, is at once restrained and candid in his remarks. An extended clip from the aborted "I Claudius" (1938) is included, in which Charles Laughton is staggeringly good (although much of his completed footage was reportedly quite a mess). The interview finishes with Sternberg demonstrating how he lit his scenes, using two Swedish children who wandered into the studio. He cuts holes in a piece of cardboard — making a primitive gobo — holds it up over the light, and you have those very same mysteriously enigmatic shadows that made Dietrich famous. All within one box set from Criterion.

*

Speaking of 1920s melodramas, we have the 1927 silent of Maurine Dallas Watkins' Chicago [Flicker Alley]. This is not the well-regarded 1942 "Roxie Hart," which starred Ginger Rogers, but an early version filmed while the original 1926 play was still on the boards. This "Chicago" was not a von Sternberg production; it was Cecil B. DeMille, of all people, and it is extremely watchable. (DeMille produced it and is said to have directed it, although the film bears another director's name.) Phyllis Haver makes a fine and memorable Roxie; she is joined by Robert Edeson as Billy Flynn and Hungarian actor Victor Varoni as Amos. Turn-of-the-century Broadway star May Robson appears as matroness Morton, while lothario Caseley is played by none other than Eugene Pallette. (He turned into an expert — and famously rotund — comedian in films like "My Man Godfrey," "The Lady Eve," and "Mr. Smith Goes to Washington," but is neither here.) And in the budding talent department you have costume designer Adrian and art director Mitchell Leisen. This "Chicago," long thought to be lost, was found in DeMille's private collection. It looks absolutely superb in David Shepard's restoration. Flicker Alley also provides a second disc with two worthy supplements, "The Golden Twenties" (a 1950 documentary compiled from authentic footage from the era) and "The Flapper Story" (a 1985 short interviewing some former flappers). But the "Chicago" movie and Ms. Haver are the attractions here.

| |

|

|

*

| |

|

|

*

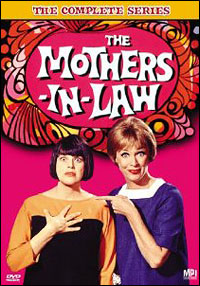

The Mothers-in-Law [MPI] was one of those often hilarious but stubbornly unsuccessful sitcoms that debuted back in those long-ago days when hair was something you combed or fluffed, and Nixon was just some washed up ex-Vice-President. Ah, nostalgia. The idea was to take a pair of long-time friendly neighbors — just like a suburban Lucy and Ethel — and have their kids get hitched. Turning them into too-close-for-comfort instant relatives, inserting themselves into the lives of the newlyweds and generally gumming up the works with harebrained schemes and wacky machinations. Since the Lucy and Ethel of the occasion were Hollywood's Eve Arden and Broadway's Kaye Ballard, neither of whom ever met a laugh line they couldn't milk, "The Mothers-in-Law" was — and remains — irrepressible. The Lucy link is not incidental; this is what Desi Arnaz busied himself with after leaving Desilu, the influential sitcom factory he started with his former wife, and the series was created and written by "I Love Lucy" scribes Bob Carroll, Jr. and Madelyn Davis. The show ran two seasons, starting in the fall of 1967, and the 56 episodes feature a parade of guest stars (led by Arnaz himself, and ranging from Jimmy Durante to Don Rickles — which is quite a range).

| |

|

|

(Steven Suskin is author of the recently released Updated and Expanded Fourth Edition of "Show Tunes" as well as "The Sound of Broadway Music: A Book of Orchestrators and Orchestrations," "Second Act Trouble" and the "Opening Night on Broadway" books. He can be reached at [email protected].)