*

As the twerpy ad exec on "Mad Men," Vincent Kartheiser's Pete Campbell is the quintessential character that audiences love to hate. Toiling in the shadow of charismatic alpha dog Don Draper, Pete is an often oblivious, sometimes neurotic bag of insecurities amidst a slew of strivers in a 1960s-era Madison Avenue advertising firm. With his self-satisfied smirk, grossly naked ambition, and calamitous stabs at infidelity and social climbing, Pete grates on both his co-workers and loyal viewers. Indeed, when Pete was cold cocked this season by partner Lane Pryce during a conference room fisticuffs, surely more than a few "Mad Men" fans felt a twinge of satisfaction watching the punchable Pete get popped square in the kisser. So why all the hate? Perhaps because Pete reflects back our own foibles, flaws, and insecurities.

The past season on "Mad Men" was especially hard on Pete. He slept with a prostitute, led the charge on the indecent proposal offered to Joan, and had a brief affair with a married woman (Alexis Bledel), Beth, who had her memories of him summarily erased by electroshock therapy. His despairing hospital room monologue delivered at Beth's bedside encapsulated Pete's constant dissatisfaction and offered an illuminating moment of vulnerability.

As for Kartheiser himself, in conversation he comes across as considerably more charming, content, and self-effacing than his onscreen counterpart.

Before he heads back to work on season six of "Mad Men" in late October, Kartheiser is in the midst of stretching his stage muscles, playing a smart young novelist, Sebastian Justice, scarred by deep loss and post-9/11 trauma in The Death of the Novel. In the drama by Jonathan Marc Feldman, now playing to Sept. 22 at San Jose Rep in California, Kartheiser's character has a bestselling, critically acclaimed post-9/11 novel under his belt. But he's lost faith in himself and the world and become a recluse who hasn't left his apartment in two years or written a word since. Then one day a mysterious stranger enters his cloistered world, offering redemption and hope. In a recent interview, Kartheiser talks about his own youthful cynicism, the unhappy ambition of Pete Campbell, and tackling his first stage role in seven years.

You play the brilliant novelist Sebastian Justice in Death of the Novel. He's described as the most well-adjusted depressed agoraphobic in Manhattan. Who is this guy?

Vincent Kartheiser: Sebastian is really emotionally detached from people, because he's lost pretty much everyone he's cared about in his life. They've passed away. His mother, his father, and the love of his life. Three very significant people. So he's in a place where he has a lot of anxiety about opening himself up to other people. He also has a lot of skepticism, because he realizes that everyone wants something from him. His friends maybe want to use him to get laid. Other people want to use him to get into the writing or publishing business. So he approaches every new relationship with a big dose of cynicism, because he's always trying to find what a person's angle is, what they're trying to get from him, or what his value is to them. I think anyone who has reached a certain level of success or fame has to deal with people coming into their life for the wrong reasons, and he's just hyper-aware of it.

|

||

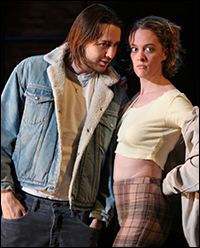

| Vincent Kartheiser and co-star Vaishnavi Sharma |

||

| photo by Aja McCoy |

VK: Well, not on the same level, because I haven't had the same level of success — nor am I as self-conscious or as successful or as intelligent as this character. But I can see how he would feel that way, yeah. I've been around people who have had similar attributes or are in similar situations, and I think it is scary for them to invite new people into their lives, because everyone does seem to want something from them.

So what is the catalyst that finally draws him out of the cocoon of his apartment and back into the world?

VK: We're trying to build an anticipation about what will get this person writing again. What will get him inspired to have a level of hope or optimism about life? And how do we get inspired? [The play] speaks to the times. It's topical for that reason. We've been going through this Depression for the past four years, and I think people are kind of looking for a reason to have hope and looking for a reason to have inspiration.

There's a character in the play, a mysterious Saudi woman, who intrudes into Sebastian's self-contained world. Who is this woman and why may she not be the person she says she is?

VK: She's invited into his apartment, because one of his friends wants to impress her, and she's a big fan of Sebastian's book. For Sebastian, it's kind of love at first sight. He falls for this girl immediately. And she begins to construct this fiction about her life and who she is. He can see the holes in her story, but he makes a choice to love this kind of living piece of fiction. And it's what gets him to fall back in love with the idea of writing and the idea of telling stories.

What first inspired you to want to play this part when you read the script? What was the hook that grabbed you?

VK: There's certain pieces of this play that I think hit the nail on the head when it comes to understanding men in their 20s. It's something I related to. I remember feeling the way that Sebastian feels. And I think that the play will speak to audiences because there are a lot of people out there who don't believe in love or that they can give it to anyone. They don't believe that there's really anything great in the world. That's a character I really wanted to play, because I feel that there is another side to it, and I wanted to show that transformation. I also knew it would be a big challenge to take on a role that has so many psychological dimensions. I'm always looking for opportunities to do things that seem maybe a little bit out of my league. [Laughs.]

|

||

| Vincent Kartheiser |

||

| Photo by Aja McCoy |

VK: No, I've always kind of had a foot-in-the-door in the industry. I've always been very blessed in that way. But when you're young, sometimes your perspective is skewed, especially for this guy Sebastian. His perspective is that everyone he loves has died. "So why get connected to anyone? We're all going to disintegrate and decompose. That's the only real truth out there. Wasting your time writing books or trying to change the world isn't going to change the world. You're not going to save anyone's life. Everyone's going to die. So what's the point?" But I think that approach to life is a perspective thing. Of course, if you don't feel that way in your 20s for a little bit, then you're probably not really searching the ranges of your psyche. But if you've kind of not gotten over it by your 30s, you maybe never will. For me it was just a phase. I definitely explored it. Then I grew up. Was there a turning point when your outlook changed?

VK: I think it gradually wore off. It just takes a huge amount of energy — that sort of emoting and ennui. Eventually I just got so busy that I didn't have time to be that cynical anymore.

The playwright Jonathan Marc Feldman said that he'd seen you on "Mad Men," and he thought you'd be a good match for Sebastian, even though Pete Campbell is such a different character. How would you compare these two men?

VK: Sebastian is someone who has achieved a certain amount of success. Whereas Pete Campbell, for a good part of his time on television, has been yearning for that success. Sebastian reached it at such a young age, which has such a different impact on you. He doesn't have that inferiority complex that Pete has. If anything he has a superiority complex. And he doesn't want to be involved in the world. Pete Campbell's whole life is built around basically entertaining people and trying to move his way up the social ladder and be accepted by people. Whereas Sebastian is trying to exclude people from his world. He doesn't really believe that there is a social ladder.

"Mad Men" creator Matthew Weiner has remarked of Pete and Don, "We all want to be Don Draper. But we're all actually Pete Campbell." Do you think people react negatively to Pete because he holds a mirror up to our own faults and foibles and vulnerabilities, which is a hard thing for viewers to face?

VK: Well, even Pete Campbell thinks he's Don Draper. Pete Campbell feels that he's charming and he's all those things that Don Draper is. He doesn't realize how the outside world sees him. I don't think he realizes that the world doesn't view him as Don Draper. He thinks he's as smooth as Don is. And that's what makes that character work. I mean, he has to believe that what he's saying is the cleverest thing — even though everyone in the room realizes that he's putting his foot in his mouth once again.

In what ways have you personally connected with Pete in his journey over these past five seasons?

VK: Well, he's me. I mean, he's parts of me. I obviously relate to him in some ways. We both are beta men, basically. I'm a beta male. He's a beta male. We both have inferiority issues, probably. And we both have a high level of ambition, although my level of ambition is very different than his. But it is something that I share in common with him. And we're both constantly sticking our feet in our mouths as well. I oftentimes say things that are so stupid, and the second I hear them come out of my mouth I wish I could take it back.

I think we all have those moments.

VK: I don't know. I really don't know if some people do it as much as others. I think some people are very gleefully ignorant of their social ineptitude.

|

||

| Vincent Kartheiser on "Mad Men." |

||

| AMC |

VK: No. I don't think Pete beats himself up. I think Pete thinks that he should be praised. I think Pete thinks he does a great job all the time — and is shocked that he's not made like the President of the company and that people don't like carry him around on a chair everywhere he goes. But Pete sees his life, and he says, "I have nothing. I haven't gotten what I deserve. Everything in my life is not as good as it should be." Whereas I look at life, and I say, "Hey, I've gotten a lot more than I deserve. And my life is way better than it should be." [Laughs.] Will Pete Campbell ever find a sense of happiness or fulfillment? Or will he always be searching for something more?

VK: We had a line this season where Don Draper says, "You know what happiness is? It's that moment right before you want more happiness." And that's what "Mad Men" is about. "Mad Men" is not a story about like, you know, everyone getting married, and then all of a sudden all their dreams come true. It's a real life story about what it means to be a man of ambition and ego and flaws in that decade. Those men aren't happy.

Happiness for them is not a destination. It's not even a journey. It's an impossibility. Like so many people in life, it's insatiable — you know, this quest for happiness, this quest for success, this quest for respect. So if they were to be all of a sudden given that, I don't know how the show would continue to make sense.

Tell me about your stage roots. You got your start performing at the Guthrie Theatre in Minneapolis as a kid. When was the last time you were on stage?

VK: Theatre is where I began acting when I was 6 years old. I did lots and lots of plays both at the Guthrie and the Children's Theatre Company in Minneapolis. So I developed my acting skills at both of those places. Then I started in TV and film, and I kind of left theatre behind for a little bit, because I wanted to go and get a foothold in the industry — in television and film. Right now I've had theatre on the back-burner for a while. But it's something I've always enjoyed doing and I've always loved. So it's always a joy when I get the opportunity to do it. I did a play in my mid-20s in New York City, another new play, another very difficult play to interpret. It was at the Cherry Lane Theatre. That was the last time I was on stage doing a play. So I very much look forward to getting this one up in front of people and starting to get some feedback.

|

||

| Kartheiser and Polly Lee in Slag Heap. |

VK: I don't know if I should tell you. [Laughs a little.] The play was called Slag Heap [2005]. I don't think it's ever been done again since then.

How was the experience for you on that play? Was it a good one or leave something to be desired?

VK: The experience was absolutely wonderful. I really enjoyed the director we worked with, and I loved the other actors. But we didn't really sell any tickets. [Laughs.] When there's more actors on stage than in the audience, that can really be a hard thing to swallow. What's the adjustment been like transitioning back onto the stage after years of doing series television like "Mad Men" and "Angel" and film work like "Rango" and "Another Day in Paradise"? The process and mechanics can be very different.

VK: For me the biggest change between television and film and theatre is the length of rehearsal and the way you approach rehearsal. That's really the biggest difference. In TV and film, you almost have no rehearsal at all. You just show up, you show 'em what you're doing, you take some notes, you do it again, and then you move on to the next scene. The great thing about doing theatre is that you get this opportunity to really work it out — to really explore new things, go home, sleep on it, come back the next day and say, "I have this new idea." Try that out. Realize it's shit. Go back to the old idea. Come up with a new idea. Do that all over again. That's something that you don't really get in doing film and TV work. In film, usually you're like driving home and you get a great idea, and you're like, "Oh shit, I should have done that!" But you don't get the opportunity to do it again. It's already been filmed, and it's going to be there forever. And your great idea is just a thought in your head. It can never be tried.

You've said that you're something of an adrenaline junkie. Is that one of the major attractions of doing theatre for you — satisfying that craving for an adrenaline rush?

VK: It does give me that punch of adrenaline that I need. When you're on stage, it's this do or die thing. You're out on a limb, and in that moment feel so alive. But for me, doing this play is about challenging myself as an actor—spreading my wings and trying to reach different boundaries of my own abilities—and hopefully fail pretty epically.

So you're not afraid of failure?

VK: I embrace it. I mean, I'm terrified of it — absolutely. But that's what makes it worth doing. Any actor, any person who is involved in the creation of something regardless of what it is, will tell you that it's only through failure that any sort of real growth happens.