*

In a more than five decade-long career, Frank Langella has acted alongside a glittering array of famous stage stars and Hollywood A-listers, from Laurence Olivier, David Strathairn and George Clooney, to Whoopi Goldberg, Jeremy Irons, Alan Bates, and Ryan Gosling. But for his latest film, "Robot & Frank," which opened in New York Aug. 17 and rolled out to select cities on Aug. 24, Langella has a most unusual co-star — a diminutive plastic robot with a disembodied voice. (Often brought to life by a young circus performer wearing a robot suit.)

In the film, set in the not-too-distant future and directed by newcomer Jake Schreier, Langella plays aging former jewel thief suffering from the early stages of dementia while living alone in a house upstate. His daughter, Madison (Liv Tyler) is off trying to save the world. And his son Hunter, who drives hours to visit his father every week, finally insists that dad needs a live-in caretaker — a robot — or else he'll be forced to move him into a "memory center." The cantankerous Frank is at first annoyed and unnerved by his new spaceman-looking helper, dismissing it a "hunk of crap." But as the robot makes his soothing and surreal presence felt, Frank takes a shine to it. The machine (voiced by Peter Sarsgaard) convinces Frank to eat healthier and exercise more. But as Frank's short-circuiting mind improves, his old larcenous self emerges. And he convinces the robot to help him execute a final elaborate heist, to which the robot reluctantly agrees. Frank's one human friend remains Jennifer (Susan Sarandon), the tender local librarian who the hardened old thief clearly adores.

Over the years, Langella's film and TV career has ebbed and flowed. While he now frequently seen as a leading man on Broadway, he's become a well-respected, go-to character actor on film — with roles ranging from Clare Quilty in Adrian Lyne's adaptation of "Lolita" to former CBS titan William S. Paley in "Good Night, and Good Luck" to a swashbuckling New York Knicks owner in "Eddie," where he met former flame Whoopi Goldberg. His most famous stage and screen role, of course, was this lusty Count Dracula — seen on Broadway in 1977 and on the big screen in 1979. The performance transformed Langella into a matinee idol and caused women in the theatre to faint at the sight of the smoldering vamp (apparently prefiguring the "Twilight" phenomenon).

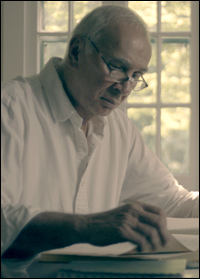

Another high water mark of the Langella's career came in 2007 with his haunting turn as a disgraced Richard Nixon in Frost/Nixon. For the 2008 big screen adaptation of the play, director Ron Howard considered major Hollywood names like Warren Beatty and Jack Nicholson. But he eventually settled on Langella, and the actor went on to pocket an Oscar nomination for his performance. Indeed, Langella, 74, has recently enjoyed a late-career run of critical success as a cinematic leading man, albeit in mostly low-budget fare. Not only did he nab that Oscar nomination for "Frost/Nixon," but he earned glowing reviews for his performance in the 2007 indie "Starting Out in the Evening." As the retired teacher and nearly-forgotten novelist Leonard Schiller, locked in a May-December romance with an ambitious young grad student (Lauren Ambrose), Langella imbued Schiller with a magisterial combination of wisdom, wonder, and pathos that was as unsentimental as it was moving.

With his turn as Frank Weld in "Robot & Frank," Langella may have scored yet another late-career triumph. (Once again, he reaped the reward of being the producers' second choice, landing the part after Christopher Walken turned it down.)

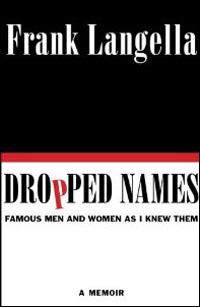

Now in his eighth decade, Langella shows no signs of slowing down. This past spring, he published a delightfully dishy celebrity memoir, "Dropped Names: Famous Men and Women As I Knew Them." The book, which received admiring reviews, revealed insightful and not-always-flattering personal anecdotes about his experiences acting, socializing, flirting, and sleeping with a panoply of famous faces, from Elizabeth Taylor and John Gielgud to Noel Coward and Jackie O. The New York Times called it a "no-holds-barred eulogy somewhere between mash note and carpet-bombing" that "painted Hollywood and Broadway as teeming with vulgar, neurotic, and irresistible company."

Here, Langella dishes the dirt on the memoir, the new film, and his colorful career on stage and screen.

You've acted alongside a myriad of illustrious stage actors and major Hollywood stars during your decades-long career, from Laurence Olivier, Rita Hayworth, and David Strathairn to Jeremy Irons, Whoopi Goldberg, and Alan Bates. So was it a especially unique challenge acting opposite this inanimate, robotic creature with a disembodied voice? How in the world did you approach that?

Frank Langella: Well, I've actually acted opposite some live, animate creatures that had less to give than the robot gave. [Laughs.] It was actually wonderful to act opposite the robot. I enjoyed it because I had a very clear notion in my head how my character felt about the robot. So I didn't have to concern myself about interpretation. Frank felt a very particular way. So it wouldn't have mattered if whoever was saying those lines said them in Dutch, French, or Chinese, or whether they were male or female. The robot was the robot to me, and I had a very strong reaction to it.

How would you describe Frank's reaction to the robot? And how does it change over the course of the film?

Langella: Unsentimentally, guarded, determined, and very subtly becoming, if not dependent upon the robot, somewhat awakened by the robot. Because whether or not it's animate or inanimate, everybody needs nurturing and everybody needs validation and everybody needs to feel that something or someone cares. I think the subtle message in this movie that's set in the near future — in which more and more people in Frank's situation might find themselves being looked after by some inanimate object — is both terrifying and sobering. So Frank changes because something is combing his hair for him and making his meals and cleaning up around him and saying "You matter to me. I'll teach you to garden. We'll go for a walk." He changes. And also he discovers that he can teach the robot tricks that he knew in life. It's a sort of bittersweet message, which is that we all want connection. And our society and times are getting to the point where it may be that more and more people will be getting it from inanimate objects.

| |

|

|

| Langella in "Robot & Frank." | ||

| photo by Ruby Katilius - Samuel Goldwyn Films - Stage 6 Films |

Langella: Well, I think all of those cliches that are said by me and you and everybody are absolutely true. It's not making us closer. It just isn't. It's alienating us. More than alienating us, it's giving us the opportunity to satisfy just about every human interaction without another human being. I'm sort of surprised someone has not yet invented, you know, the sex machine, which was prevalent in the movie "Barbarella" [1968]. You just get yourself into a machine and get all the sexual pleasure you want, under your own control. I'm surprised that machine doesn't exist—and it will, I'm sure it will. Then people can say, "Well, I really don't need anybody. I can do everything on my own now." Which of course will be further sadness. But that's where we're heading.

| |

|

|

| Langella in "Robot & Frank." | ||

| photo by Ruby Katilius - Samuel Goldwyn Films - Stage 6 Films |

Langella: Yes. I see it as inexorable in place of Armageddon. You know, if Armageddon comes, then everything will start at creation again and build up very slowly. But if we continue the way we have—and we don't end up destroying ourselves or another nation doesn't destroy us — yes I see it as inexorable. More and more gadgets and things attached to you on all parts of your body are going to determine emotions and feelings and everything. And maybe the human brain will change over the next centuries and decades. When fewer and fewer people are required to interact with each other, people will become born with less need for human contact.

My understanding is that there was an actor/performer wearing the robot suit. And of course the robot didn't have Peter Sarsgaard's voice until it was added in post-production. What was the challenge of that aspect of making the film — acting opposite a gymnast in the robot suit?

Langella: That really was the least of the challenges. I'm asked often about, "Was it difficult?" It wasn't. In a way, there was a certain liberation about it. I mean, the most challenging part of making this movie was the stifling heat of keeping my concentration in 100 degree weather. But the robot was not in any way a challenge, because Frank was very much who he was and wasn't about to let anybody in. So it wouldn't have mattered what the robot sounded like; I just acted opposite something I wished wasn't in my life. I just had a very particular feeling towards this robot.

Is there a critique about how we treat the elderly and the sick in this film and about the loneliness and isolation of aging?

Langella: I don't think it's a movie that proselytizes at all or says "This is how we treat the elderly." If anything, Jimmy Marsden's character [Hunter] really cares. It's Frank who doesn't care. And his daughter [Liv Tyler] cares in a different kind of way. Certainly the character he's interested in romantically, Jennifer [Susan Sarandon], cares about him in a way that we discover later. But I don't think the movies says that these people treat Frank badly. If anything, they treat him with great compassion. He's the persnickety one. He's the one you want to slap around. He just can't seem to feel for others.

| |

|

|

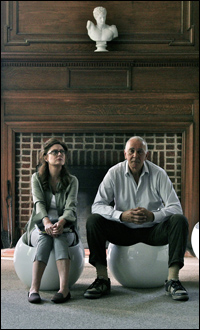

| Langella and Susan Sarandon in "Robot & Frank." | ||

| photo by Ruby Katilius - Samuel Goldwyn Films - Stage 6 Films |

Langella: Well, I think about it all the time. But I don't think about it related to the number of years I've been around. I just think about it in terms of: I see more and more people in their 50s getting ill and actually dying. A friend of mine, who was 59 years old, died of a disease he only was diagnosed with 10 months ago. That you become more aware of it, of course, as you get older. But I don't think because I'm 74 it's going to happen to me any quicker than it might happen to you. It just happens to people. They wake up one day with a headache, or they stumble a little, or they get hit by a car and are crippled. All the things that you just don't even think about. They don't even cross your mind when you're growing up and making your way [in the world] and making children and forming families and making a fortune and all the things you feel you need to do. Which are all immensely distracting from the real reasons to be alive. But one day you look around and think, wow, someone I really love and care about got diagnosed with brain cancer 10 months ago, and now he's dead. It just happens so rapidly, and things changes so quickly. He was perfectly fine. We were working on a project, and two weeks later he looked enormous from steroids. That happens constantly — all the time now. I'm aware of how quickly life can change.

| |

|

|

| Cover art for "Dropped Names: Famous Men and Women As I Knew Them" |

Langella: No, I think they go away from you. It isn't that you shed them. If you're smart, then you let go of them. You let go of wanting to hold onto them when you feel them disappearing. All those things that you thought you needed to get you through a day. In everybody's case it's different: A lot of booze, a lot of smoking, a lot of sex, a lot of money, a lot of fame. All the things you think are worth pursuing, as you get older you realize they really are useless — and pointless. You just come to value, more and more every day, good health and human contact. And Frank of course is someone who's got a wall up against all of it. There's that wonderful scene in the movie where Jimmy [Marsden] berates him and says, you know, "You could talk anybody into anything. But you never were there as a father. You don't care. And here I am, busting my balls to help you, and you just don't care." What I like about this movie, more than any other element, is its total lack of any kind of mushy sentimentality — either related to the children or related to the robot. Frank remains resolutely what he is — right until the end of the picture.

Your scandalous, dishy new memoir "Dropped Names," which was released in the spring, caused quite the stir as well as some admiring reviews. What compelled you to write it?

Langella: Some of what we're talking about. A friend of mine died, and I had lost contact with her in the last decade of her life. Ms. Jill Clayburgh. I didn't know how sick she was. I was traveling with a companion, and she showed me the obituary, and she's a fair amount younger than Jill and didn't know who Jill was. And I was taken by the fact that she didn't know who Jill was. So I sat down and wrote my memories of Jill. It was the first thing I wrote. And then I just thought, wait a minute, in the 50 or so years since I was about 15, there are so many fascinating people who have come and gone in my life — and now are literally gone. So why don't I just write down my impressions of them? And then it got to be a hundred or more pages. 110, I think. And then I carefully took it down to 65. It happened very quickly. And now all my writer friends who want to kill me. I started writing it in December or November of 2010. So it was a very quick. I mean, I wrote and rewrote and wrote and rewrote all that time. But these stories just poured out.

| |

|

|

| Langella in Broadway's Man and Boy. | ||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

Langella: A little. But there hasn't been any. I was worried about maybe family members of certain people, and I was prepared to say, "Look, as I say in my book in the preface, this is my experience of that person." I'm not ever saying, "This is what they were." I'm saying, "This is my feeling about them." But there hasn't been one negative letter or email or phone call. If anything, there have been remarkable gestures and reactions. Lily Rabe [Clayburgh's daughter] wrote me a beautiful letter about Jill. And Dominick Dunne's son listened personally as I read the story about his father, which wasn't always flattering. But no, there hasn't been anybody [writing or calling me up] irate or angry or [saying] "how could you?" Not one person.

Despite the fact that it's a celebrity memoir with some scandalous tidbits and provocations, the book was widely admired for its eloquence and unvarnished honesty. One review said "There is so much happy sexuality in this book that reading it is like being flirted with for a whole party by the hottest person in the room." And Charles Isherwood in the New York Times praised it for "insight into [your] own fears and foibles that is often absent from the memoirs of celebrities" as well as its "overriding note of compassion and fellow feeling." What was your intent in writing it and what was the overarching theme that you wanted to communicate?

Langella: I didn't have a theme other than they were all dead. But I suppose if you look at the book — and I'm now re-reading it in order to correct the typos for the paperback [edition] — it's really about the remarkable schism between the famous face that walks into a room and what's going on in the soul of the person. All of the different qualities and the complexity of being alive. As I say in the final chapter, in the Afterward, "If you stick to your soul, it will stick to you." So many people in my profession don't stick to their soul. And they end either tragically or sadly. And it takes a lifetime to understand that simple phrase. But I think if there is a theme in the book, it's the idea that being famous is really not a very important goal. It's like money, wealth, sex, you know, physical pleasure, honors, awards, titles, all those things — they just come and go. On "Charlie Rose," you talk about that a little bit — the idea that life is about the journey. You quoted what Ortega said in "The Revolt of the Masses": That the best place to be is in the water and trying to get to shore and never getting there, because that means you're alive.

Langella: Right. Because once you're there on shore, what else is there? It's better to stay in the water and just swim. Just swim and always look in the distance for a place to land — but don't land. One of the things I say is: I don't think there's any comfort in the safe landing. People are always saying "It's time to settle down." That's just nonsense. Keep flying. Always keep flying. It's better.

| |

|

|

| Langella as Richard Nixon on Broadway. |

Langella: Getting him was harder than any part I've ever played. Finding him was the hardest time I ever had in creating a character, in finding him. I was positive I was going to fall on my ass in that part — even through the final stages of rehearsal, before we faced an audience. I thought, I just can't find this guy. For a long time, I really felt that he sounded like Mr. Magoo. Or Jimmy Stewart. You know, wah, wah, wah, wah, wah. I couldn't get a noise. And I knew I didn't want to imitate him. I knew I didn't want to try to phonetically or in any other way capture his sound. It had to come from inside of me. So I just doggedly, every day, kept returning to the idea of what's going on inside of him. And then the character slowly developed out of that.

So was it hard to find him because he was one of the most complex characters you've ever played?

Langella: No, it was chiefly an obligation to his fame. I knew that I could have played him in any number of ways. But I knew I had to find a certain allegiance to capture a sense of him. I just couldn't go too far afield from his physical awkwardness, the kind of odd way he spoke. I knew I couldn't suddenly give him a Southern accent or make him, you know, incredibly graceful. I knew I had to honor certain things about him, and then I had to find deep within myself those qualities that I felt best projected him.

So were you disappointed when names like Jack Nicholson and Warren Beatty were being floated for the film version of "Frost/Nixon" despite the fact that you had done it on stage and won a Tony Award for your efforts? Or were you resigned to losing out on the part considering the realities of Hollywood?

Langella: I thought that this was not going to be one of my successes. I thought I would play it for eight weeks in London, for a few hundred pounds a week, as a great sort of challenge to see if I could do it. I had no idea that it would then be a year of my life — first as the play and then another year as a film. So it was all gravy after the initial beginning of it. And I was perfectly prepared for it to be played by a leading movie star.

But you were thrilled when you landed the part in the film version, when they finally offered it to you?

Langella: I'm too old for thrilled. [Laughs.] I was pleased, let's put it that way.

| |

|

|

| Langella in the "Frost/Nixon" film. | ||

| © 2008 - Universal Pictures |

Langella: Oh, sure. When you can't speak, when you get all tongue-tied in front of a girl when you're young, or when you get scared of authority figures or you get resentful — any of the things you get because you're shy and awkward — one of the best places to take refuge, I suppose, is this sense that you're going to get lost in being somebody else. Then if you're smart, after a while you realize that being an actor does not mean running away from yourself; it means running towards yourself; it means embracing everything about you that's complicated and difficult and turning it into art. You know, using it as a weapon, so to speak, against the worst in you.

Do you approach your work on screen differently than your work on stage? What are the differences for you as an actor in bringing to life characters on stage versus characters on screen?

Langella: I now love being in front of a camera more than I've ever loved it. I think in the last decade I have really enjoyed film work more than stage work. I really love them both. And acting is acting. But the medium of film is very exciting to me now, because the effort to try to communicate something with just the raise of an eyebrow or a tiny look or a small gesture is very rewarding if you can manage it. So yeah, I love film work now — more than I ever have.