*

Hollywood history is littered with big stars stepping behind the camera lens to try their hand at directing — some churn out successful, even masterful films (see: Clint Eastwood, Warren Beatty, John Cassavetes, and the recent likes of Ben Affleck, Sean Penn, and Philip Seymour Hoffman), others deliver exercises in ponderousness and mediocrity (we won't name names).

Ralph Fiennes can already imagine some of the catcalls that will be lobbed his way from the smirking, brow-furrowing masses who may well greet news of his directorial debut, a cinematic adaptation of Shakespeare's Coriolanus, with skepticism or, worse, outright derision.

Indeed, when some people hear that a major screen actor will be setting himself up in the director's chair, their internal warning lights often start to blink red. Beware: self-aggrandizing vanity project ahead.

Explains Fiennes, in an interview during a brief stopover in New York City to promote "Coriolanus": "It's a natural course for many actors. But I think people often go, 'Oh, you're going to direct now, are you?' There's a slight wariness when an actor takes that leap and says 'I want to direct.' So if you're a first-time director, there's then a huge question mark above your head. People don't know what you are. They might like the idea, but they're not sure…" People may be especially doubtful considering that it's not only Fiennes first time behind the camera, but he's also adapting Shakespeare for the big screen — never an easy prospect. Plus, "Coriolanus" is one of the Bard's less-well-known tragedies — not a name-brand property. And besides, who does Fiennes think he is — Kenneth Branagh? (Oscar winner and Tony-winning Red playwright John Logan wrote the new screenplay.)

Still, despite his training with the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art and decades of experience performing Shakespeare with the likes of the RSC and in other prominent theatres (he won the Best Actor Tony for playing Hamlet on Broadway in 1995), Fiennes admits, with a smile, "I know that lots of people thought I was mad. A lot of people didn't know the play. They just thought, oh, it's a difficult one, isn't it? That was the first thing people said, 'Why not choose something easier?' But in my head, it wasn't difficult because I had such a strong feeling about it. I just had a very strong sense of the world I wanted."

Indeed, Fiennes' keen interest in adapting Coriolanus can be traced back to playing the part in an acclaimed production for the Almeida Theatre in 2000, which traveled to London, Tokyo, and the Brooklyn Academy of Music. He couldn't get the part of the feared and revered Roman military general out of his head. Thanks to the play's propulsive narrative drive and what Fiennes saw as its cinematic qualities, the actor became increasingly intent on the idea of developing the play for the big screen.

|

||

| Fiennes on set |

||

| The Weinstein Co. |

A feared and revered Roman general, Coriolanus (nee Caius Martius) was raised in an aristocratic military family. He's a man of unshakable courage and integrity, but falls victim to his own unstinting pride and honor, because he struggles to sympathize with the pain and suffering of the Roman people.

Fiennes imagined a "Coriolanus" set in a contemporary-seeming world of intense 24-hour network news coverage, violent street uprisings, behind-the-scenes political machinations, guerilla insurgencies, urban warfare, and a food crisis highlighting the rising inequality between the wealthy haves and a general population of have-nots. (Indeed, "the 99 percent" protests would no doubt resonate strongly here.)

"I wanted to keep the Shakespearean language," says Fiennes." But the question was how to make it accessible and attainable and immediate. The modern world seemed like the best route."

The story commences with Caius Martius winning a key battle against the insurgent Volscian forces in a long-running war between the two nations. Triumphantly returning to Rome, Martius is bestowed the title of Coriolanus and reluctantly thrust into seeking the powerful government position of Consul by his mother Volumnia (Vanessa Redgrave). While he has enough votes in the patrician Senate and the support of his friend, the influential veteran pol, Senator Menenius (Brian Cox), he must also win support from the general populace. Unwilling to play political games and reluctant to engage in the glad-handing and campaigning necessary to capture the seat, Coriolanus awkwardly garners the support of the masses at the city marketplace. But he's almost immediately outflanked by his political enemies, who brand him an arrogant military man and accuse him of representing a threat to the interests of the people. With lightning speed, they turn the tide of public opinion against Coriolanus, as the masses gather in angry demonstration against him. A disgraced Coriolanus is quickly banished from Rome. Bitter and stateless, he makes his way to the Volscian capital of Antium where he swears loyalty to his longtime rival, Aufidius (Gerard Butler), leader of the Voscian army and vows to take revenge on the Roman people for their ingratitude and treachery.

"I think it has such extraordinary scope and an epic scale to it — of warfare, social and civic unrest, unrest on the streets," says Fiennes. Despite the actor's enthusiasm for the project, he and his producers struggled to ferret out financing for the film in the wake of the financial crash of 2008, but they eventually found backing.

"It couldn't have been worse possible timing to make the film. But funnily enough, the economic and social uncertainty that provides the backdrop [of the film] is now all around us and part of our conversation. So the timing seems to have worked out quite well. I think things have popped up into high definition now. But I think Coriolanus is a play that always has something to say to us."

|

||

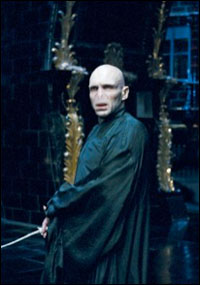

| Fiennes in "Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix." |

||

| 2007 Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. |

Indeed, for Fiennes, there's no rest for the weary. He recently wrapped a two-month turn as Prospero in The Tempest at the Theatre Royal Haymarket in London. Now he's off to shoot two films in a row — director Mike Newell's new adaptation of Dickens' "Great Expectations," in which he's playing Magwitch; then Sam Mendes' upcoming Bond film, "Skyfall," in an unspecified role (though speculation is rife that it will be another villainous turn). Both films are due out sometime next year. In the following chat, Fiennes talks about the challenges of making the leap to the director's chair, what drew him to the difficult role, why he wanted to set the film in a contemporary world, and the enduring power of Coriolanus to reverberate across time.

The R-rated picture, from The Weinstein Company, opens in Los Angeles and New York City on Dec, 2, and nationally on Jan. 20, 2012.

*

Have you been thinking about trying your hand at directing for a long time? What drew you to what to direct?

Ralph Fiennes: It sort of emerged, I think, over time. I had thought about directing. But it must be the case with a few actors. They think about it. But to actually break through that barrier and say, as it were, to the world, "This is what I want to do," is quite a leap … I got a lot of confidence from a man called Simon Channing Williams, who produced "The Constant Gardener" and produces all of Mike Leigh's films. He wanted to produce my first film as a director. Sadly, he died about two years ago. But he actually gave me a project that he had, and we worked on it, and I went and did some location scouts. And we pushed it along to the point where we were trying to cast it and really find out the heads of department. But we couldn't get the financing for it. So, sadly, that film didn't happen. But having worked with him on that project gave me a confidence. He was a very experienced producer and so wasn't going to go to that trouble lightly unless he had a strong hunch. So that gave me the confidence to, as it were, literally step forward and say, "I'm going to do 'Coriolanus.'"

The second validation I got was from [the film's screenwriter] John Logan, who, when I pitched it to him, he loved the idea and almost immediately wrote a first draft. We sat together and shared and pooled our ideas. And he wrote this most amazing screenplay. But he is, you know, a very successful screenwriter getting all kinds of offers, who does not have to take time out to take on a Shakespeare just to indulge an actor. So when I think he saw the seriousness of my idea and how I had thought it through, and he liked it, that was a second impetus for me wanting to pursue the film.

What about Coriolanus, the play, made you think it would make a good film?

RF: Well, I think what often makes for a good film is sort of mixture of the epic and the intimate. So you have a background that has power and size and stature. So that you feel when you look at that screen, you're visually stimulated—photographically. But also I think we are drawn to strong, highly defined characters and their journeys. It's a high-octane drama [that's] essentially familial. …That combination makes it, to my mind, very filmic.

There's [also] political power shifting that goes on and on. I feel that Shakespeare presses that button quite hard. Aufidius says at one point, "One fire drives out one fire. One nail; one nail." There's this sense of one force driving out the next — this continual, infinite swapping of political power that goes on ad nauseam forever and ever. I think Shakespeare is showing us that whoever is in power is turned over by the next person and by the next person and by the next person. And then the people are sort of left fighting to make sense of their lives.

|

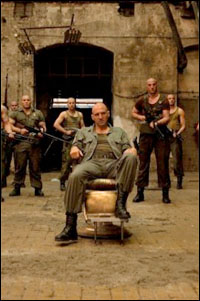

||

| Fiennes in "Coriolanus." |

||

| The Weinstein Co. |

RF: Dramatically what's exciting is that Shakespeare puts his very confrontational protagonist at the center of the drama, and it's quite risky. He's like a sheet of granite — Coriolanus. He doesn't like anyone particularly, except those closest to him. And that's a challenge to an audience. But that's always excited me. And I find that part of me is sympathetic to him. Because even though I don't probably sympathize with his views, I sympathize with the man trying to stick to his truth, even though we don't like his truth. But at least we have to give him credit that he's trying to hold to it. And he's maneuvered and manipulated by people. But he's trying to hold to a sense of extreme integrity. He's a complex figure. He's emotionally quite stunted and compressed. He has emotions. But he's not someone who knows how to express them. He's a warrior, and that's the way I understood him — as a soldier or a samurai. The samurai has a very strong set of principles. And they're prepared to die for their honor. Where he experiences any kind of ecstasy or elation is in the battlefield. So I think that's who he is. But negotiation is not part of his DNA.

He seems to reject political gamesmanship and that whole world. Is that an outgrowth of him being a warrior and a military man?

RF: I've always felt he's been conditioned, very particularly by his mother, by a military ethic of service. What makes good generals is a kind of ruthless sense of order, and the whole function of an army is dependent on people following orders and being prepared to put themselves on the line and being prepared to die. That's why there's all this [stuff surrounding the] cult of the warrior — its rituals of honor and medals and awards. That's why military structures have this highly defined code, which is there to support a mystique that helps give them courage. So that's why I think you can see [that] the person who's been in the service treats the civilian world as completely different. The luxuries that a civilian has, the latitude that the civilian has to express [him or herself], it's foreign to him. Coriolanus is an extreme warrior. So the civilian world, he has no time for it. People protest, and they're hungry. But he's been on the front lines, and he's been prepared to die many times. So he can't comprehend their point of view. He just can't understand it. He thinks that is disloyal. Actually, you see it in some more right-wing publications here, you know. The New York Post, today, saying, "Enough!" for the protestors down on Wall Street. "Shaming New York City by your protests." That's not far from how Coriolanus would feel.

|

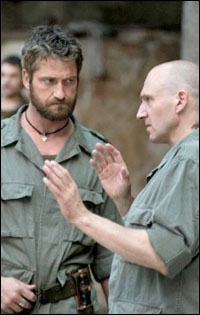

||

| Fiennes and Gerard Butler on set |

||

| The Weinstein Co. |

RF: The role is challenging on stage because the interior life is not really expressed. He doesn't have many soliloquies. There's maybe one soliloquy, which even then is not very introspective. It doesn't let you, the audience, into his life particularly. What the audience receives is a man being angry, mostly. So the challenge of the part is to find the nuances, because a lot of the time it's clear from the text that he's in a state of aggression or anger or confrontation. So I felt that it could be revisited in terms of the camera being able to go into him, into the mother, into Menenius.

One of the things that John Logan thought was exciting was that the close-up of Coriolanus is what you never get on stage. You never really see and hear from him all that much. I love the play. It's provocative, and it doesn't give you any neat, compact message about what's right and what's wrong. I think it's possibly quite nihilistic. But it asks a lot of questions, and it confronts the audience with a panorama of dysfunction in the world, which is what I see around me. I think we're completely dysfunctional as a [human] race. And I think that this play exposes that brilliantly in the form of this tragic drama.

What are some of those questions that you think the play raises?

RF: Who should you trust? Who should you follow? When should you be loyal? Do you think it's right to change your mind on the turn of a [dime]? [Snaps fingers.] You vote for Obama one day, and then the next day you change your mind. Or do you? Or should you stick to your principles? You were a loyal Democrat when Obama was voted in, then suddenly you've lost patience. Why? Are you disloyal? Or do you think you're justified? Those are difficult questions to grapple with.

RF: Yeah. You know: "Where are your loyalties?" — that's what it's saying. Or, "Are you right to change your loyalties?" "Hey, ho, tomorrow I feel that I'll go here." You know, actually, we're all like that. We all do it. We all change and shift. I think it confronts us with our shiftiness. [Smiles.] It says, "Do you have the guts to be a Coriolanus?" None of us do. And, actually, if we do, we'll probably end up like him, because unless you're prepared to negotiate and shift, you probably don't survive. So it sort of presses the buttons of our instinct for survival. We have to negotiate, to compromise, because if we don't, we end up dead maybe, or we probably don't get very far in life.

Can you talk about the enormous influence of Coriolanus' mother on him and how she's shaped him to become that man that he is?

A: She's the mother of all mothers. And the confrontation between mother and son is where the play, I believe, leads. That's where it's leading. It's presenting us the shifty, changeable world of politics and society. But actually where we all come from is from the womb of our mother. And that final moment [in the play] is about that. And what's tragic about it is that this man, whether you like him or not, he has tried to hold to his principles…And sometimes he is a boy. He holds to his truth like an adolescent sometimes. But then he cracks finally. He makes peace. He's a peacemaker. And he dies because of it. And I think often with a tragedy, you in the audience are asked to be sort of a witness to the demise of a person. The pitiable state of mankind is exposed in a great tragedy. And I think you're asked to witness it.

Why set the play in a contemporary world, or a world that's not our own but that looks and feel contemporary? Much of the film feels like you're turning on the television or opening the newspaper and reading about current events.

RF: Well, I just wanted an immediacy. And I believed that [a contemporary setting] was the best way to establish an immediacy and an intimate connection with the world of the play. I was absolutely set on it being contemporary. For me it has an immediacy: I know that politician getting out of that car. I know that combat guy. I've seen him every day on the news and in the newspaper — that man in that camouflage uniform running down the street, through the smoke and the dust. I've seen the people protesting on the streets, in their hoodies and jeans. You know, that's our world. I wanted the audience to visually connect with it right away — as a way to help them follow the story. Because I knew that both John and I wanted to stay with Shakespeare's dialogue. Also, I was encouraged by the success of the Baz Luhrmann "Romeo + Juliet," which I think was a brilliant film and completely says to its audience, "Here's this world. And people speak like this, and this is what we're doing." He presents a completely brilliant, clear world. You don't quite know where it is, but you know the world. Somewhere, we've seen it.

|

||

| Vanessa Redgrave in "Coriolanus." |

||

| The Weinstein Co. |

RF: Yeah. It's a world with a petrol stations and high rises and helicopters flying overhead, and there are limousines, and there's a wealthy family with a swimming pool. And we know that world. We see it in magazines. We see it in movies. Maybe our friends have a house with a swimming pool…. So you felt that Baz Luhrmann's "Romeo + Juliet" showed you could adapt Shakespeare into a contemporary setting on the big screen, attract an audience, and maintain the language?

RF: Of course there's always going to be the question of, "Why keep the dialogue?" I think there's an expressiveness in the dialogue that is thrilling. And once people get on board, I believe they will follow it. Absolutely, I felt I wanted to keep the Shakespeare — 100 percent. I think the language is extraordinary. But I don't see it as being a problem. I think a bit like listening to a dialect, your ear has to really engage.

Is a big part of any success casting actors, like Vanessa Redgrave, who could really speak that Shakespearean language in a way that felt contemporary and immediate?

RF: I mean, there isn't one right way to speak Shakespeare. Shakespeare's language should feel real. But there are moments when it's quite heightened, definitely, and it's overtly poetic. And there are other moments when it's a very loose verse form, which can be spoken so naturalistically, you wouldn't know whether it was prose or verse. It doesn't really matter. It's just: How is it being inhabited?

You said you watched Gillo Pontecorvo's seminal documentary-style war film, "The Battle of Algiers" (1966), as an inspirational reference point for the film. How did that film become something of a touchstone?

A: Well, because of his way of capturing the sense of The Street, the aliveness of the Street, the movement on the Street — the faces, the people — real people, you know, in crowds, particularly. Watching the film, you feel that it could be a documentary. So those faces were important to me. It was important that they were the real thing, that they weren't from Central Casting.

What other influences or inspirations did you look to in adapting the play for the big screen?

RF: I had a whole massive trove of imagery: Still photographs of war zones, riots, politicians' faces. There's a fantastic photographer called James Nachtwey, who's done a great book called "Inferno," which is photographs of these war zones and trouble spots in the world. That book was hugely influential for gathering imagery. Things like the murdered family in the car that [Aufidius] discovers — those sort of images, that photography played into making that scene happen. You know, the complete horror of just aimless violence, which you see in the shot of bodies on the ground. So those were influences in terms of photography.

|

||

| Fiennes in The Tempest |

||

| photo by Catherine Ashmore |

RF: There were bits of people. But there really wasn't one person that I based it on. I think a lot of acting is imagination…But in my office in Belgrade, I had a Caravaggio painting on my wall as a sort of lighting reference, particularly for the scene in which I encounter [Aufidius] in his underground lair in Antium, where he's hiding out. I thought the lighting should have a certain feel in those scenes. So Caravaggio's paintings and their Biblical content meant something for me there. Things like the woman coming in to cut the hair and shave Coriolanus has the sort of Biblical feeling of a traveler being washed. I also had a Francis Bacon painting on the wall — so the sort of entwined bodies of Aufidius and Coriolanus as they fight should subliminally suggest a sense of male coupling. I also had pictures of General Stanley McCrystal on my wall — before he had this drama with the Rolling Stone magazine article. I didn't know much about him, except that he was a highly respected general, admired by his troops and incredibly tough. But his face — he's in a military hat, a beret and everything — was Coriolanian to me. And I had a couple of Petraeus, too. But McCrystal's face has a sort of real overt toughness in it, which I liked. So that was on the wall in my office. Also, I had some images of Putin. He's not really Coriolanus, but the completely detached look of Putin in his eyes is quite scary and was quite useful. And there were Donald McCullin's photographs of Beirut in the early '80s. All these things are like visual emotional triggers that feed into your imagination. But also just looking in the paper every day. I mean, I started the whole process off because I was tearing out the front page photograph from the [International] Herald Tribune, which is always electric as a piece of photography. Iraq, Afghanistan, even the 2008 riots in Athens —all that stuff played into how we made the feel of the film. What were some of the biggest challenges of simultaneously acting in and directing in the film?

RF: Probably what you would imagine. How do you sort of go from looking at a frame and discussing a position of a camera and a performance, and then how do you go in front of it and then immerse yourself in it? And that was hard — made particularly hard because I think there's a necessary time that you need [as an actor]. Every actor needs the time to go…to come from their dressing room, where they've done their teeth and they've put on their costume, and then they go and they…I mean, every actor is different. But there's a time where you go, "Now I'm actually consciously making the effort to think about what I'm about to do, whatever internal process I have, I'm engaging with it — imaginatively, emotionally, spiritually, physically, whatever. And now I take that time to do that. And that's why on a set, people go, "Are you ready? Should we wait? Should we set up? O.K., let's have quiet now." Because there's an awareness that some kind of transformation or transition has to happen. And that takes some kind of time. Some actors, they might keep everyone waiting, because they're not there [in the right mind set or frame of mind] yet. But under time pressure, because we had so little time to do these scenes, where we probably had on average half the time you normally schedule, that was hard. I mean, there were days when it was just really hard to hold the part in my head as the actor. But I had a wonderful team with me.

What Shakespeare adaptations do you think have translated well from the stage to the screen, and were there reference points in those films that you looked to for inspiration?

RF: There were fantastic sequences in Orson Welles' "Chimes at Midnight." Amazing battle sequences in that. Although arguably things will always date, I do think that there's a wonderful visual coherence to Olivier's "Hamlet," with the castle and the mood of that. You know, maybe the performance style is still very close to something theatrical. But it's a very committed filmic gesture — brilliant. And also there's the Russian director, Kozintsev, who did a "Hamlet" and a "Lear." I haven't seen the "Lear" since I was at school, but the "Hamlet" is amazing. And also Peter Brook's "King Lear" with Paul Scofield. I love that for its real austerity. I think there's a wonderful understated quality to performance [in that film], which I loved.

You might just be the hardest working man in show business. You recently finished up a stage turn in The Tempest in London; you've just been announced for Sam Mendes' new Bond film, and you're about to shoot Mike Newell's new version of "Great Expectations. Are you worried about the, um, expectations, for a classic Dickens work?

A: Well, with "Great Expectations" you're on hallowed ground, of course. Because David Lean's [1946] film is sort of sacred almost in British cinema history certainly. I think, you know, it's a great film. But I think there is room for another version. So we'll see.

Christopher Wallenberg is a freelance arts and entertainment writer based in Brooklyn. He's a frequent contributor to the Boston Globe, Playbill and American Theatre magazines.