*

After spending the past five years working in the formulaic, often stultifying world of network television on the ABC family melodrama "Brothers and Sisters," Rachel Griffiths worried she'd been forming some bad acting habits.

Sure, the Aussie actress was acclaimed for bringing to life the outspoken, temperamental Brenda Chenowith (girlfriend-turned-wife of prodigal son Nate) on the trailblazing HBO drama "Six Feet Under," a role that garnered her a Golden Globe Award, two Emmy nominations, and a legion of fervent admirers.

But while playing Brenda from 2001 to 2005 on "Six Feet Under" was a high water mark of Griffiths' career, for the past five years she's been best known as the headstrong eldest sibling Sarah Walker, a focused and frank businesswoman, on the (some critics say) frustratingly uneven ABC television series "Brothers and Sisters." So when that network decided not to pick up the large ensemble show for a sixth season, Griffiths says she knew it was high time to challenge herself as an actress and reinvigorate skills that she felt had atrophied. She began thinking about returning to her stage roots, which led to her making her Broadway debut last month (to March 4) in Jon Robin Baitz's politically-potent family drama Other Desert Cities, a play that's become one of the biggest hits of the fall Broadway season.

"I have been overpaid and underworked for too long," says Griffiths, during an interview in the basement green room at the Booth Theatre, on a recent Wednesday afternoon between matinee and evening performances of the play. "And I needed to be underpaid and overworked…So I just felt it was time. It was time to go get my chop-chops back. You kind of get habitual, and you kind of fake it and wing it. You have to. I mean, you can't work a 14-hour day making television at a certain level of truthfulness. But you do your best to be present in the moment." Griffiths, who turned 43 on Dec. 18, says she didn't even realize how much time had passed since she was last on stage — in 2002 in an Australian production of the Pulitzer Prize-winning Proof for the Melbourne Theatre Company, a performance for which she captured the Green Room Award for Best Actress in a Leading Role.

"I said to my husband, 'God, I haven't done theatre for like five years!' And he goes, 'Honey, I got some bad news for you. It was eight,'" she says, bitingly, punctuated with a sly smile.

Not that the actress is showing any signs of rust from her time away from the stage, having earned solid reviews for her performance in the Baitz play. "A beautifully modulated Broadway debut," praised the New York Times' Ben Brantley. While The Hollywood Reporter's David Rooney gushed that the play had "acquired a riveting center in the raw performance of Griffiths, who makes a knockout New York stage debut."

In this dysfunctional family drama, Griffiths plays Brooke Wyeth, a liberal New York literary star and daughter of conservative Reaganite parents, who returns home for the holidays brandishing a bombshell revelation. After a period of dormancy in which she battled depression, Brooke has written an explosive roman à clef memoir that pulls back the curtain on a troubled chapter in the family's history, involving her dead brother who committed a horrific crime in his rebellious youth.

|

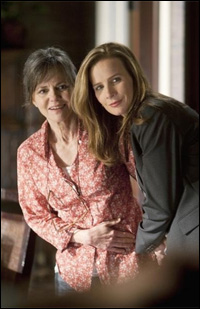

||

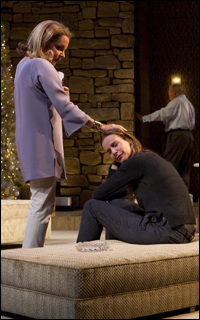

| Griffiths and Stockard Channing in Other Desert Cities. |

||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

Griffiths describes the Baitz play as a "chamber piece," with each actor functioning as a musician who takes the melody of the piece for a while and runs with it. "It's a baton, and somebody passes that melody back, and you pick it up. And then it has these two big mountains that we have to climb — a little mountain at the end of the first act, and then this big mountain at the end of the second — which are classical in their proportions and drive in a way…where you're sustaining emotion and language at a really high pitch."

|

||

| Griffiths in Other Desert Cities. |

||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

During rehearsals and preview performances in October, Griffiths and Light, the two new players, had to mesh in with the other three members of the ensemble. Griffiths may have earned rave reviews for her performance when the play opened to critics in early November, but it wasn't an easy process to get there. Indeed, she says she didn't really nail the last — and probably biggest — piece of the puzzle until a few days before opening night: Understanding Brooke as a writer.

"[Director] Joe [Mantello] and Robbie were telling me, 'You're not getting the writer thing. The mother thing is coming. The betrayal's coming [through]. The grief [part] is coming. The rawness of this is coming. The being-part-of-the-family is coming. You know, your [relationship with your] daddy's coming. The cost of giving up this family [part] is coming. But you're not getting the writer.' Which is 'the head' part of it. The heart stuff I really understood…I haven't read a lot since my kids were born. So I think I'd really forgotten a lot about writing. How writers think. How they justify the books they write. How they hurt people in the writing of those books. How despite that, we're often glad they wrote them. "I've kind of been dismissing a little bit the importance of her book. So I stepped that up. And then the night before opening, I was like, There's something I'm not getting about this woman," she says, with a whisper. "And then it just came to me in an epiphany. I was like, 'Oh my god, she doesn't have kids. I have children. She doesn't have children.' And as much as you understand the juggling of a working mom, the working artist is a whole other thing. Because the truth is, once you have children, you tend to continue to work, but it's extremely hard to work in that maniacal way — of which most truly good work is born. Particularly, I think, in writing, because it requires you to isolate yourself and not engage."

|

||

| Griffiths in Other Desert Cities. |

||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

To get in the mindset of a writer, each night before she heads out on stage, Griffiths listens to the audio book of Joan Didion reading from her new memoir "Blue Nights." "I listen to her for 10 minutes talking about her daughter [Quintana]. There's a certain kind of detachment in the way she wrote 'Blue Nights' that's very helpful."

To further rev herself up for the show, Griffiths says that she blares David Bowie's "Space Oddity" (the "Major Tom" song) inside her dressing room, straps on her "space helmet," and acts out the song doing "bad Aboriginal dancing," she says, with a wry smile. Is she kidding? Apparently not. "You should come up for one of my 'Major Tom' performances," she insists.

|

||

| Griffiths and Thomas Sadoski in Other Desert Cities. |

||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

"That you can be so with her, and then in the next act you're so sure she should not do it. She should just go back to therapy and work it out. Or she should just put it in the drawer and publish it after they're gone," she says. "But then you're like, 'Oh hell no. These people have spent their career shaping a false narrative. You should blow the f---ing thing up. Why should they own this narrative — which is entirely invented anyway?'" Griffiths says that Marvel's performance helped point the way for her about certain things she would need to do and shifts that would have to happen with her character.

"Having said that, I'm a different actor, and I bring a whole bunch of different textures And then as you're doing it, you can only do it as yourself — especially with only two weeks of rehearsal. I just had to make it as close to myself as I could, which I did. And then I had Robbie and Joe telling me what I wasn't getting, which was the writer [aspect]."

Griffiths mentions a few specific aspects of character she's playing a little bit differently from Marvel, different territory that she's been charting.

"There were certain relationships I wanted to explore in a different way, particularly between me and Lyman. The kind of father-daughter thing — the all-American princess. In American culture, I find that really interesting. So the wistfulness of that I thought could be affective."

Dressed casually in jeans, a light blue hoodie, and black Chuck Taylors, Griffiths is speaking between bites of a gooey chocolate and coconut Australian treat called a Lamington. (A friend of her dresser, Ryan Rossetto, made a delicious tray of them for Griffiths, her co-stars, and crew members.) Her hair is long and straight, light brown with blondish highlights, and she has a pretty, sharp and angular face.

Slipping back and forth between her native Aussie accent and the Americanized inflection of her character, Griffiths evinces a cool, questioning demeanor. There's a take-no-bullshit aspect to her presence. She has a wry perspective on the world but doesn't try to be funny or toss off perfectly biting quips. Her husband, Andrew Taylor, is a painter who's having his first New York show this month. She's a mother to three young children (two boys and a girl) — all under the age of seven.

|

||

| Griffiths in "Muriel's Wedding." |

Riddled by self-doubt and serious self-sabotaging tendencies, Brenda grappled with a seemingly endless torrent of personal challenges — including sex addiction, a tumultuous relationship with her parents, a manic-depressive brother, a roller-coaster love affair with her boyfriend-turned-husband Nate, and his eventual death after he unceremoniously dumped her on his deathbed.

"I think Alan Ball created a female character that had never really been seen on television before and that was completely unbound by what a female character on television was supposed to be. And we were depicting the sexual lives of women in a very candid way…I also think it was me not limiting the character based on what I thought a female character had to be on television. I approached it in a similar way to all these indie movies I'd been doing."

While much of the audience loved Brenda for her complexity, the character also deeply alienated a segment of the TV-watching populace. Indeed, Griffiths concedes that "people either loved her or hated her."

"Some fans couldn't stand her. I remember, Peter Krause [who played Nate] was driving across America, and he was in the middle of nowhere at some truck stop. And this guy comes up to him and is like, 'Hey! You that dude?! You that dude on that show about the dead people?'" explains Griffiths, adopting a thick backwoods-hillbilly inflection. "And Peter's like, 'Uh, yeah.' And the guy goes, 'Hey, what you gonna do about that girlfriend of yours? You gonna kill her, man?! I'd f---in' kill her! You gotta put the bullet in her!'" Griffiths continues, punctuated with a gale of bemused laughter.

|

||

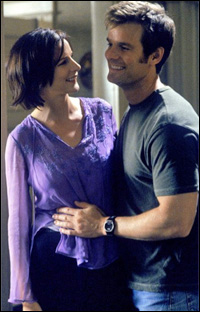

| Griffiths and Peter Krause in "Six Feet Under." |

The success of "Six Feet Under" and other likeminded cable series, she thinks, is a reflection of a contemporary writing sensibility that combines the bleak and tragic with wacky or withering comedy.

"Alan [Ball] knew he couldn't go torture us longer than six minutes without the best fucking joke we'd heard. We'd laugh our asses off and just feel like we're on this roller-coaster. I think the best contemporary writing in film and TV and the theatre — and you know Robbie [Jon Robin Baitz] does it — is about laughing in the face of death," she says. "And I'm comfortable in that. I can play both edges. I think it's our generation. We want it mixed up a little bit. We don't want to feel safe in just a straight comedy, and nor do we want to put through two hours of drama without the odd relief."

A memorable moment in "Six Feet Under" that exemplified the mingling of pathos, despair, and leavening comedy was when Maggie, who slept with Nate right before he died, showed up at Brenda's house to offer an olive branch and perhaps seek forgiveness. "I brought you a quiche," said Maggie, a soft-spoken Quaker. To which a distraught Brenda, mourning Nate's death in the wake of their marital trouble, replied with a retort so withering it could've melted steel, "What is this some kind of bizarre Quaker thing? You f--- someone's husband to death, and then bring 'em a quiche?" before slamming the door in her face.

"I like big transitions, those heady moments of flipping-a-scene-on-its-head or taking an audience from a laugh to a cry," Griffiths says, snapping her fingers. "Which Stockard does in this show, too. You're laughing at the beginning of a line, and by the end of the line, the actor has taken you to a whole other place. That's exciting. It's kind of gymnastic and athletic, and it's what keeps it super-interesting."

"Brothers and Sisters" was a different kind of experience. She thoroughly enjoyed playing Sarah Walker, a more level-headed character than Brenda but one who had her own outbursts of scathing wit and brutal honesty. There were big aspirations for the show, considering the pedigree of the cast and creative team.

But Griffiths acknowledges that working on a broadcast network series was an up-and-down creative experience, especially when it came to the meddling of some executives and producers. "Working in a network environment, there were compromises and crazy shit going down that was much less negotiable [than with 'Six Feet Under']. You would be asked to do stuff that made no sense. And then people would tell you that the reason it made no sense was because they'd received a very nonsensical note from someone that made no sense. And yet there was no recourse."

Indeed, after one and a half seasons shepherding the series he created, Baitz was forced out after increasingly agitated creative differences with the network and other producers. Baitz has said he wanted to explore thorny issues of race, sexuality, and politics within a family of smart, middle-aged characters, and he lamented the show's increasing focus on the younger demographic and soapier shorelines. Still, Griffiths says that Baitz's exit from "Brothers and Sisters" was the absolute best move for him.

"I felt it was probably time for Robbie to stop, because it was costing him too much. He was still trying to do something extraordinary in an atmosphere where that was extraordinarily difficult to insist on doing. For his self-preservation as an artist, I think it was better that he stopped getting beaten up with baseball bats by a bunch of opinions," she said. "Having said that, I think it made him a better writer. You know, this play has drive. It really looks after an audience. It's so satisfying — the plotting and the unveiling of secrets."

|

||

| Griffiths and Sally Field on "Brothers & Sisters." |

||

| photo by Randy Holmes – © 2010 American Broadcasting Companies, Inc. |

What she first loved about acting was the spontaneous creativity of improv-style theatre games. "It was so fun, because we just made up shit all the time — shows and plays and scenes and improvisation…I loved the kind of crazy creativity of that," she says.

"Then as I got older, I just liked the exploration of the human being in living, breathing, three-dimensional form. I found it more satisfying than the academic analysis of the human being, from a sociological, psychological, sociopolitical, or political point of view. I found that actually being inside a character and exploring it was more fun."

She says she thinks she was destined to become some sort of artist.

"If I didn't end up as an actress, I would've ended up as someone like Tracey Emin — you know, like putting my bloody sheets in a tent and exhibiting that. To me, to separate what's crucial and critical and fundamental about life from your work — spending 10 or 12 hours a day — seemed like an insane idea to me. So I had to find some job where the two met."

|

||

| Griffiths on opening night |

||

| photo by Joseph Marzullo/WENN |

"It's a girl's story that's hip and funny and sweet and heartbreaking," says Griffiths. "So that's a big reason that we're going back to Australia."

She also hopes to return to the stage in the coming year, perhaps acting in something at the Sydney Theatre Company, run by Cate Blanchett and her husband, Andrew Upton. "I want to try to make that work, so that might be the next play I'll do."

Indeed, Griffiths says Blanchett had suggested a part for last season, and they had a number conversations about it, but "I was just finding it hard to commit, because it was so far off, and Sydney is not my hometown," she says. "So I passed on something that I was really quite rueful about. It was a very hard decision."

Griffiths will also be seen in the upcoming Australian indie, "Burning Man," opposite Matthew Goode, which screened at the Toronto Film Festival this year. "It's all told from the point of view of a man who's basically going on a sexual rampage after losing his wife to cancer. But there's some big laughs. It's funny, but black," she says.

So does Griffiths see herself returning to the network television milieu? "I was joking to my agent recently, 'I'm really over playing complicated people. I just want to be the D.A. bitch in leather on 'Hawaii Five-0,'" she says, with an exuberant laugh.

Now that she's gotten a handle on playing Brooke, what she's struggling with most are the distractions of live theatre, such as latecomers and ringing cell phones that seem to go off at every performance, especially during those Wednesday matinees.

"Today, there were nine phones that went off in the first act alone. I almost lost it. Everyone keeps telling me, 'You've got to suck it up. You've got to get professional.' But it was driving me crazy!"

Still, she says, there's absolutely nothing like starring in your first Broadway play. "It's so electric on Friday nights. I just love those Broadway houses."

More than anything, though, Griffiths cherishes the time she has left playing such a meaty and fulfilling role in a play she adores. "I just loved the piece so much the first time I saw it," she says. "I loved its elegance and its audacity. I loved what a great night I had. I loved how much it made me feel and think and how it created this world that I'd never been in before, that stayed with me for a tremendously long time."

Christopher Wallenberg is a freelance arts and entertainment writer based in Brooklyn. He's a frequent contributor to the Boston Globe, Playbill and American Theatre magazines.

View highlights from the show: