*

In February of 1956, a press conference was held in New York heralding what Joshua Logan called "the best combination since black and white," and, at the time, it didseem like a great idea — pairing the ultimate actor with the ultimate sex symbol — but, by the time the project rolled into production in the U.K. in July, the color scheme shifted to black and blue: the clang of titans with easily bruised egos.

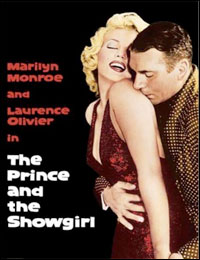

Sir Laurence Olivier and Marilyn Monroe came together as co-stars of "The Prince and the Showgirl" at cross purposes (compounding that problem, he directed and she produced): Olivier craved her popularity with the masses; Monroe, longing for his prestige, hoped for a little gilt-by-association. Neither won, but their film was "not an un-success." Fated the fail from the get-go, they never let their chaos spill onto cinematographer Jack Cardiff's sumptuous view of 1911-vintage England.

Olivier and his wife, Vivien Leigh, had done the play (by their pal, Terence Rattigan) on stage as The Sleeping Prince, and, although the new movie title made a more apt plot synopsis, Olivier said he felt he was in "a Betty Grable musical." Actually, the plan was to musicalize the play, but Monroe's new hubby, Arthur Miller, scotched the idea, leaving Noel Coward free to tune up The Girl Who Came to Supper, separately.

|

||

| Poster art for "The Prince and the Showgirl" |

"The Prince and the Showgirl" is not the stuff of serious film study. The only reason it comes up now is because of the literary droppings of a go-fer on the set, providing a fly-on-the-wall perspective of the ensuing rants and rampages on Mount Olympus.

Colin Clark, as befit the son of historian Lord Kenneth Clark, kept a detailed diary of his first film job — Third Assistant Director, which here roughly translated as Monroe wrangler. At 23, he was an unswerving protector for the fragile star — often, her most trusted touch with reality — an experience that produced fodder for two memoirs and (albeit, posthumously) movies: "The Prince, the Showgirl and Me" became an hour-long 2004 documentary of archival footage; its more intimate sequel, "My Week With Marilyn," is now a feature film, now in movies theatres, with a bygone Olympus cluttered with Michelle Williams (MM), Kenneth Branagh (Olivier), Olivier- and Tony-winner for Red Eddie Redmayne (Clark), Julia Ormond (Leigh) and Dougray Scott (Miller).

|

||

| Michelle Williams in "My Week With Marilyn." |

||

| photo by Laurence Cendrowicz – © 2011 The Weinstein Company |

Broadway's Kathleen Marshall, who choreographed some of Monroe's better-known numbers for Williams to do in the picture, has called Williams a natural for musicals, despite the actress' protestations to the contrary. "I'm not a singer or a dancer," Williams said in a recent press conference. "I haven't been on a stage doing both of those since I was ten years old. In some ways, because of that, I felt like — when I was able to put the nerves aside — I really felt a tremendous outpouring of joy. I felt like a little girl whose dreams came true for the first time, and I was able to tap into what I would imagine made Marilyn Monroe so luminous in those singing and dancing numbers.

|

||

| Kathleen Marshall |

||

| photo by Joseph Marzullo/WENN |

After the Monroe ordeal, Olivier directed only two movies. Both were filmed records of Chekhov plays he had helmed on stage, and, in both, he also played doctor-in-the-house: Dr. Astrov in Uncle Vanya and Dr. Chebutykin in Three Sisters. A 19-year-old Branagh, woefully too young for the 60-ish Chebutykin, dashed off an S.O.S. to Olivier, asking for advice and getting it — his one brush with the great actor.

"I got his address out of Who's Who in the Theatre," Branagh recalls, in a chat with Playbill.com, "and I wrote him and said, 'Dear Sir Laurence, Any ideas on how to on play this part, which you do magnificently and I'm so ill-equipped for?' And he wrote back, briefly, to my amazement, to say, 'I don't really have any specific ideas. This is something you must work out for yourself. My advice is to have a bash at it and just hope for the best.' "When it came to playing Olivier here, I bore that advice in mind. I thought, 'Let's not get worried about walking in the footsteps and shadows of giants. Let's just do it.'"

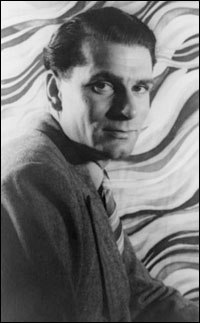

This is not just idle bravado for Branagh. It seemed only a question of time till he actually turned into Olivier, having been listing in that direction for quite a while.

As director and/or actor, he gamely re-filmed Olivier triumphs (Henry V, Hamlet, Othello) and staged other screen Shakespeare (Much Ado About Nothing, Love's Labour's Lost and As You Like It). For "Dead Again," he even looked like the graying-at-the-temples Olivier of "Rebecca."

Constant comparisons made Branagh so thick-skinned that he wasn't cripplingly intimidated when director Simon Curtis pitched the part of Olivier to him.

|

||

| Olivier in 1939 |

"I was circumspect when it came up only in the sense that I wanted to feel that an appropriate treatment was at hand. I suppose I wanted to feel that the script loved these people, even if that didn't necessarily mean they were painted in a hagiographic way. They could be there, warts and all, as long as somehow it acknowledged how bloody marvelous they were at what they did. I felt that, in a strange way — in the way that one's name has been linked to his in the past — that it was such an obvious thing to do that it was a dangerous thing. I liked the danger of it. I liked, that neither sounding nor looking like him much, there would be a great big leap to take there — that the physical process of doing that would be fascinating."

Prosthetics and clever camerawork help Branagh bring off some astonishing approximations of Olivier's Prince Regent of Carpathia, materializing through a thick monocle and unidentifiable accent. "Then, the hair — the very pomaded, very made-up look Olivier had in the movie." Terence Stamp, a buddy, badgered him into getting "a pair of handmade shoes from a place called George Cleverley's in London — a shoemaker to many, including Laurence Olivier — and I bought them as a kind of insanely extravagant treat for myself for my 50th birthday. They were ready in time for the movie. In fact, they're featured. Simon Curtis gave them a close-up."

|

||

| Monroe and Olivier in "The Prince and the Showgirl." |

||

| Warner |

In contrast, Olivier came off a stuffy sparring-partner. "I think he absolutely had a view on this kind of indistinct, East-European accent and that kind of character. The responsibilities of directing, and dealing with, her meant he was fairly inflexible about his character. To me, he is always riveting. I think he is magnetic in it, but I think it is perhaps a brilliantly misguided performance for the eventual movie."

The artist in agitation is Branagh's main meal here, but he was surprised to find some sunny contrasts in Olivier as well. "Despite it's clearly the time in the movie when we see all of the frustrations he had, I found that we also see other moments once we get under the skin of it all. There's a series of on-set photographs that were particularly interesting to me. Half of them have Olivier being very concentrated, as one would be directing the film, and half of them are Olivier as a kid by the camera, looking at Marilyn with his jaw open just like a kid on Christmas morning.

"That thing that Michelle said about this issue that makes greatness in actors or performers — sometimes I think it is to do with access to a child-like quality that means they're completely in the moment. When you're upset, you're fully upset — all of you. When you're happy, you're deliriously, fulsomely happy. When I was a kid first working with Judi Dench, that's what I observed in her — this capacity to be wholly in the moment. In these pictures of Olivier, that's what I was surprised by. Whatever the grand master of the English theatre was, he was also a kid with a train set, loving it, just loving it — and actually being really impressed and bewildered by how she did it, really fascinated by that. Whatever masks he put on — "Cut," "Well done," whatever — he was basically a guy who loved what he was doing."