*

Sidney Poitier, who (depending on your source) turned either 84 or 87 on Feb. 20, spent about eight months on Broadway, all told, in his career — seven of those at the Ethel Barrymore in A Raisin in the Sun, Lorraine Hansberry's 1959 landmark play about a struggling, aspiring family on Chicago's Southside. But the desire to return to the scene of that triumph has never really deserted him. The opportunity to do just that was the driving force that got Thurgood to the page and then to the stage and now to the HBO screen, where it debuts Feb. 24 with Laurence Fishburne in the role of Thurgood Marshall, the legendary Civil Rights leader who, through legislation, rewrote human history in America.

Now that it can be told, playwright George Stevens Jr. is telling it: He wrote this one-man show with Poitier specifically in mind and often at his encouragement.

Nor was it the first Thurgood part he had pitched in Poitier's lap: Twenty years ago, Stevens wrote and directed "Separate But Equal," a TV film about the historic 1953 Supreme Court desegregation case, Brown v. Board of Education, where a perfectly cast Poitier fought the Thurgood fight and carried the country a giant step forward.

"Six years later," Stevens recalls, "I'm having dinner with Sidney and his wife and my wife in Los Angeles, and I say to him, 'What are you up to?' And, in that princely way of his, he looked at me and said, 'I have not been on the stage since Raisin in the Sun 40 years ago. I want to go back to Broadway.' As I remember it now, I said, 'How about I write a play about Thurgood Marshall?' — thereby sentencing myself. "And I did. In fact, Sidney and I had apartments in the same building in Los Angeles, and he used to come down to mine, and we'd read it" — but, by the time the play was finished, Poitier felt "he wasn't really ready to do a one-man play," and he passed.

Director Leonard Foglia and James Earl Jones, fresh from On Golden Pond, directed and officiated respectively when Thurgood finally premiered in the spring of 2006 at the Westport Country Playhouse. Joanne Woodward, who ran the joint, and husband Paul Newman were first to champion the work and showed up when it bowed at the Booth on Broadway two years later, starring Fishburne. It would be one of Newman's last public outings.

| |

|

|

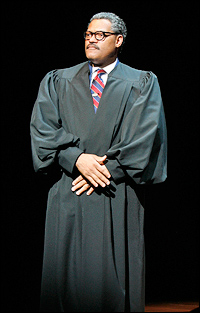

| Laurence Fishburne in "Thurgood." | ||

| photo by Carol Rosegg/HBO |

Stevens' son, Michael, who directed the television transference of the play, caught Fishburne in Fences at the Pasadena Playhouse and thought he could successfully straddle the old and young worlds of Marshall. His dad agreed: "We decided that he was our future, and I think he turned out to be the perfect person."

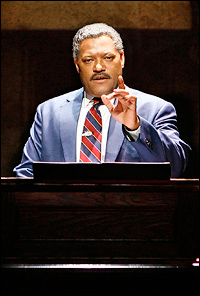

Fishburne put in 126 performances of Thurgood on Broadway, from April to August 2008 — earning a Tony nomination for Best Actor along with a Drama Desk Award for Outstanding Solo Performance — and last summer he took it up again at L.A.'s Geffen Playhouse and DC's Kennedy Center, where it was filmed over four performances on a weekend. "I think Laurence, having had that role in him for a year and a half, was noticeably deeper when he got to Washington," opts Stevens.

"Thurgood was a great storyteller. Sandra Day O'Connor, in an eulogy, spoke of the nine justices sitting in the conference room. She said, 'Every so often, sorta late in the afternoon, Thurgood would look across at us and say, "I'm going to tell you a story," and he'd describe experiences in his life laced with sadness and filled with humor, but they applied to the case at hand.' That was his special gift."

Born in Hollywood the son of a famous film director, Stevens is home-based in Washington where he is something of an emperor-in-residence at the Kennedy Center, having pretty much set the gold standard for awards shows by producing annually "The American Film Institute Salutes" and "The Kennedy Center Honors."

| |

|

|

| Laurence Fishburne in "Thurgood." | ||

| photo by Carol Rosegg/HBO |

Even a longtime hold-out from public celebrations like Katharine Hepburn succumbed to Stevens' honors. (It didn't hurt that his dad directed her to near-Oscars for "Alice Adams" and "Woman of the Year.") More resilient was the actress who would have starred with Hepburn, had the film version of West Side Waltz happened. It's not that Doris Day hasn't been asked — repeatedly — but "I don't think she is going to ever leave Carmel or her pets," he sighs resigningly.

Burt Lancaster got away without a Kennedy Center Honor — but not without an honor from Stevens, who wrote and directed the actor's final performance— in "Separate But Equal." "It was very important for that film because this was Sidney's first television piece, and for John W. Davis — the opposing lawyer — there were a number of fine character actors you could get to play it, but you'd know how the case came out simply by the voltage of the casting. Burt Lancaster gave his side a stature that was equal to Sidney's and made it less of a foregone conclusion.

"I called and asked him to do this quite late in the process. He read the script and said, 'Absolutely.' He wasn't worried about a lot of money. He loved to do good things. By that time, he had a hard time remembering lines, but he was very sharp. He said, 'God, I used to stay out all night and go to makeup and the script girl would hand me the pages and I'd learn them before they finished with the makeup.' So he would be very frustrated when he'd forget a line, but it was a joy to work with him."

"Separate But Equal" wound up winning the 1991 Emmy Award for Outstanding Miniseries and setting the stage for Stevens' belated (at age 76) bow as a playwright.

For the life of him, Stevens can't figure out why The Thurgood Marshall Story hadn't been told before. "Maybe it wasn't very obvious," he suggests. "Thurgood gets less acknowledgement than some other Civil Rights leaders, notably Dr. King, who was obviously a great figure, but Marshall was his architect. Without Marshall, all that other stuff wouldn't have taken place. Thurgood Marshall changed the law. He used the law to change the law, which made it possible for so much that came after."

| |

|

|

| Betty Garrett |

The closest that the big screen ever came to a song-and-dance Ruth Sherwood was comedienne Betty Garrett, who died Feb. 12 at the somehow-too-soon age of 91.

Even in her only starring role, in "My Sister Eileen," she was billed third — after her sister Eileen (Janet Leigh) and her own boyfriend (Jack Lemmon) — but such was the plight of a superb second-banana with impeccable timing and a sophisticated feel for throwaways.

And this was still pretty good hittin' when you consider that the role of Ruth, though originated by Shirley Booth on Broadway in 1940, was indisputably owned by Rosalind Russell, who got a 1942 Oscar nomination for it for the movie version of My Sister Eileen and a 1953 Tony Award for it for the Broadway musical version, Wonderful Town. Could an Academy Award for her be far away?

Yes, as it turned out — light years away: Despite a bountiful harvest of hits by Leonard Bernstein, Betty Comden and Adolph Green ("It's Love," "Ohio," "One Hundred Easy Ways," "Christopher Street," "A Quiet Girl," "Wrong Note Rag," "Conga!"), the Tony-winning Best Musical of 1953 was incredibly not turned into a major motion picture. The fly in the ointment who blocked that kick was a vindictive studio boss, Harry Cohn, the Columbia Pictures president who figured, since he had produced the 1942 flick which had inspired the Broadway edition, that he was entitled to a discount for Wonderful Town. When none was forthcoming, it was hell to pay, and hell had no fury like a scorned Cohn, who decreed he'd do his own film musical of "My Sister Eileen," forcing Wonderful Town into a one-day run on CBS in 1958.

The "Eileen" According to Cohn was to have starred Judy Holliday, but, having been part of a nightclub act with Comden and Green called "The Revuers," Holliday would not hear of it. The studio called it "a contract dispute" and started scouring the town for a suitable replacement, eventually turning up Garrett, who had been warming the bench herself for six years because of the blacklisting of her spouse, Larry Parks.

Only a Rube Goldberg could have charted the convoluted course of this comeback, but Garrett grabbed on with both hands and wrung out a wise, wisecracking Ruth Sherwood, formerly of Columbus and tentatively of Greenwich Village, writing a series of short stories about her mantrap blonde kid-sister making it in Manhattan.

Released in 1955, the musical "My Sister Eileen" was, of course, no Wonderful Town, but it did share a certain charming kinship to the Broadway show. Certainly, it was better than it has any right to be, with lively choreography by Bob Fosse (who played Eileen's chief beau, Frank Lippincott) and an above-and-beyond-the-call kind of melodic, delightful score by Jule Styne and Leo Robin (hardly slouches, these two). Garrett carried the seven-song score commendably and proved a perfect foil for Lemmon's fencing 'n' flirting, doing "It's Bigger Than You and Me."

Blake Edwards and director Richard Quine (who was Janet Blair's Lippincott in the 1942 movie) were credited with the script — a tricky proposition with lawyers in place on both sides making certain that there was no similarities between the show and the new film (even though Joseph Fields and Jerome Chodorov, who wrote the original comedy and the Wonderful Town book, got acknowledged).

The way out for the scripters was to fall back on the original source — Ruth McKenney's series of autobiographical short stories for The New Yorker. (Fields and Chodorov had utilized only the last two installments for their shows.)

The real-life sister Eileen McKenney never knew what a siren for the ages she would become. On Dec. 22, 1940 — four days before My Sister Eileen bowed at the Biltmore — she and her husband of eight months, novelist Nathaniel West, were killed in a car crash.

Better film roles should have followed Garrett's conspicuous star-turn in "My Sister Eileen" but didn't. In fact, none did. The blacklist wouldn't be broken for another five years. It was if the House Un-American Activities Committee had granted her special dispensation to do the film. Happily, her talent was such that it couldn't be buried.

(Most people, in fact, remember her as Irene Lorenzo, the liberal thorn in Archie Bunker's side on "All in the Family," or as Laverne & Shirley's landlady, Edna Babish.)

Replacing Holliday again brought her back to Broadway. She and Parks took over for the vacationing Holliday and Sydney Chaplin during the run of Bells Are Ringing.

She started in theatre, albeit ever-so-briefly in 1942's Of V We Sing and Let Freedom Sing, but Mike Todd hired her to understudy Ethel Merman in Something for the Boys. She won a Donaldson Award the year (1946) before it turned into the Tony Award, for Call Me Mister. Her last Broadway credits included being among The Supporting Cast (Sandy Dennis, Joyce Van Patten, Hope Lange and Jack Gilford), playing the Marjorie Main maid role (Irish Katie) in Meet Me in St. Louis and signing off with a blistering "Broadway Baby" in the 2001 Broadway Follies, her comic skills thoroughly intact and going on all cylinders.

In interviews, a measure of pride would usually creep into her voice when she talked about the favorite portion of her career — her two years before the M-G-M mast when that studio was truly a constantly functioning dream factory. Five of her six films were done there, all musicals. In 1948 she debuted as a nightclub chanteuse named Shoo Shoo Grady in a Margaret O'Brien movie called "Big City," and, in the starry and fanciful "Words and Music," she provided love interest for Mickey Rooney's Lorenz Hart (an improbably heterosexual romance for the gay Hart).

Her other, and last, year at this fabulous work plant saw her amusingly manhandling a spindly Frank Sinatra in both "Take Me Out to the Ball Game" and "On the Town."

In "Neptune's Daughter," she grabbed a couple of verses of Frank Loesser's Oscar-winning "Baby, It's Cold Outside," aggressively vamping Red Skelton while Ricardo Montalban is simultaneously doing the same thing to Esther Williams.

The year 1949 marked the silver anniversary of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, and, as if to prove it had "more stars than there are in the heavens," Louis B. Mayer one day ordered all of his working actors to a designated soundstage for a Class of '49 group shot.

Counting Lassie, 58 showed up in full twinkle 'n' shine. That's Betty Garrett, ninth from the left on the fourth row, between Judy Garland and Edmund Gwenn. On the other side of Gwenn was the one rotten apple in the group — wearing a trenchcoat and a scowl because the shoot was eating into her afternoon-nap time — Kathryn Grayson.

Garrett and Red Skelton sing "Baby, It's Cold Outside":