*

"For Colored Girls" is Tyler Perry's cinematic shorthand for for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf, a series of 20 poems which Ntozake Shange collectively called a "choreopoem" and kept in a perpetual theatrical swirl with an African-American cast of many colors. Said another way, these are all "Women on the Verge of a Color-Coded Breakdown."

Perry is a Renaissance man from the South. He has written, directed, produced and performed (sometimes, in drag, as a humongous black diva named Madea) a modest, middle-brow run of nine Lionsgate releases, which collectively roared commerciality (nearly $400 million worldwide). His tenth, arriving in movie houses Nov. 5, more or less refutes that, puts his fan base to an acid test and makes a sharp right turn on to the strange turf of Shange, who phrased as poetry the pain of the modern woman.

Both artists are poles — if not planets — apart, but this film fusion could move the poet more into popular mainstream where Perry normally splashes about. And his lure is one of the best assemblages ever of top, name-brand African-American actresses.

On stage, Off-Broadway and on, Shange joined six other sisters-under-the-yoke as they swept and twirled around each other till, one at a time, each took to the soap box to hold forth on her particular crisis, be it abandonment or abortion or date-rape or promiscuity. There were no name-tags, just a color for every calamity — "Lady in Red" dealt with domestic violence, "Lady in Green" with abandonment, etc. — and, at the end when the sisterhood united in one common sing-out, they made a rainbow. Perry approximates that dance/drama ebb-and-flow with a constantly mobile camera that darts from one principal's storyline to another. He gives all the women names and that necessary evil, men — then leaves them to destructive innerplay.

|

||

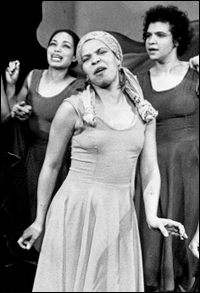

| Ntozake Shange (center), with Janet League and Trazana Beverley, in the original stage version of for colored girls... |

||

| photo by Sy Friedman |

They don't interact as much as they intersect — fractured lives that get fleeting focus and filmic fluidity from Perry. His are "women who don't know each other, whose lives are crossing," he said at the film's recent press meet at the London Hotel on West 54th. "As soon as one person would cross in my mind, I just began to follow that story. It wasn't about how much time I was giving for each of these characters as much as it was about how much of their story was being told at that moment.

"I went back to Ntozake's work and was struck by how beautiful it was. The melody of it is so great it's almost like music. What I had to do was mimic it as much as I could in my dialogue to make sure, when these women went into one of her poems, it didn't seem like a door slamming or an accent falling or going somewhere else."

Even from what you know now, you must recognize that Jackson's character screams Meryl Streep in "The Devil Wears Prada," but she offered a different reference: "Actually, there were old films that were very helpful to me. One, in particular, was 'Adam's Rib' with Katharine Hepburn."

She added, "Acting has always been a challenge to me, and that's one of the reasons I love it so much. This is a chance I thought I'd never get. I love this part — being so sure and so bold. She's got a lot of reasons to be strong, and I was up for the challenge. And the fact that Tyler had that faith in me — it really excited me, so I was ready to step forward and take the challenge."

The plot that Perry created leading up to Jackson's poetic monologue is based on a buzzword ("downlow") that didn't exist when the play was first done in California in 1974.

The most horrific of the many sad tales unfolding here is the story of Crystal, also known and The Lady in Brown. (In the stage version, for the record, the track was known as The Lady in Red.) Trazana Beverley's memorable, heart-wrenching account of it Off-Broadway at The Public won her a 1976 Theatre World Award and, when it went to Broadway, a 1977 Tony (plus virtually every other award honoring "Featured Actress" that year).

Beverley's performance has been, somewhat, preserved in a 1982 "American Playhouse" presentation on PBS in which the anguished events relayed in the monologues were acted out by men and women alike. Shange did the script herself and performed it with Alfre Woodard and Lynn Whitfield, but it was the work of the unbilled Beverley that really distinguished the effort.

|

||

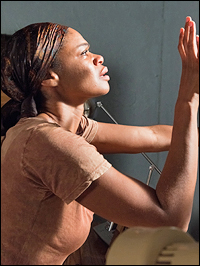

| Kimberly Elise in "For Colored Girls" |

||

| photo by Quantrell Colbert |

It took a lot to get Elise to that breaking point, she admitted — mostly, regimenting herself to her character's way of life. "I had a very peaceful, relaxed, joyous life and practiced meditation and yoga. I lived very healthy, and one of the things that I did for this was let all that go because I knew that would take me off balance. Crystal has to be off balance, so denying my character things was a lot, and it left me vulnerable and exposed and in a place that would allow her to inhabit my body and speak her voice. I went there to do this role with about five gray hairs. I came home with about 50. I'm not kidding, either. It's because — and any actor will tell you this — your body doesn't know it's pretend, and it shows up, it manifests itself. So when I came home, there was Crystal still there. I thought it would go away, and they didn't, so a few weeks ago I surrendered to my dye job for the first time and had Miss Crystal covered. And I literally did do a 21-day detox. I had to. I had to push her out.

"I knew it would be scary for me to go into that place, and I really had to build myself up for it daily to go down, down in there — and at the end of every day Tyler would say, 'C'mon back up, Kim. C'mon back up.' It really is like being underwater."

Given the depths being plumbed, director Perry sometimes saw himself as a life-guard of sorts. "I know how traumatic it can be to go that deep inside yourself to get that range of emotion, to get that kind of performance. And after it's over, it is, 'Come up. You're okay. Come up.' As we have seen in the past, there have been people who have gone to these deep places and have not been able to come out. History books are full of it, so it was important to me that after it was done to pull 'em up out of it."

|

| Tyler Perry on set with Janet Jackson |

| photo by Quantrell Colbert |

|

||

| Khalil Kain and Anika Noni Rose in "For Colored Girls" |

||

| photo by Quantrell Colbert |

The former found it refreshing: "I'm an actor, and I try always to choose something that is different from the last thing that I did. Otherwise, you just see a different shade of me. That's boring. So I just try to shake it up and find something that is challenging and different and will allow me to attempt to do something better."

Rashad found a throbbing universality in the piece. "Early on in the process of filming," the actress recalled, "we would sit in the makeup trailer, and we would all talk about anything related to the film, and it came to us all — collectively, in an instant — that all women in the world are colored girls, because the color that Ntozake Shange is referring to has not to do with the color of one's skin.

"It has to do with mood, heart, spirit, experience, emotion, expression, understanding — or lack of it, thereof. That being said, and understanding more about who the poet/playwright/star/dancer Dr. Shange is, we understand this piece as an outgrowth of her studies — in literature, in women's studies, her experiences as a professor of literature, her development as a dancer, her expression as a poet and a playwright — that's a lot. I think it's a right of passage for all people. That's what I think. When we understand women correctly, society changes. When women understand ourselves correctly, we change society."

|

||

| Phylicia Rashad in "For Colored Girls" |

||

| photo by Quantrell Colbert |

It was on the fifth bounce that Perry finally agreed to bring "For Colored Girls" belatedly to the big screen, and his hesitancy is understandable. "This is the most intimidating work I've ever taken on," he confessed. "I walked away from it many times by saying no, and then, when I'd started it and said yes, I quit four times. I kept wondering, 'Can I do this? Can I do this?' Well, once I surrendered to it, I didn't think about all that. I just knew this is special — this is very special to a lot of people — and I have to do my absolute best with it. And when I shot this film and got to the end of it, I said to myself, 'I did the best work that I can do at this time in my life,' and I was happy with that. I wrote it from a place where I thought this would work. I listened to Ntozake's voice and spoke to her many times, making sure I was on the same page.

"I've always known about women bonding, just seeing the things with my mother and my aunt and my sisters, but I've never been around this many women who bonded in this kind of way. I felt that I was in a bit of a web they were weaving around me to pick me up. They were pushing me to make sure I did a good job, as well, so they taught me a great deal. More than anything they taught me about this bond that women have, and it is unbreakable. It's a sisterhood that men don't get a chance to see so it was really a great education for me."

Tyler Perry discusses "For Colored Girls":