*

Director Michael Mayer learned a lot directing the premiere of American Idiot in Berkeley, CA, in fall 2009. And it didn't all have to do with the challenges of adapting a classic rock album for the stage.

"I learned you can drink vast quantities of tequila and still be alert," said the Tony Award-winning director, nursing a Patrón Silver on the rocks at a table on Sardi's second floor. Blame Tré Cool, the drummer of Green Day. "He has created a really good drink called the Cheech," said Mayer. "It's tequila and tonic water and...I don't know what it is. But it's very good."

His Bay Area liquor education didn't end there. "In Berkeley, in order to limit my alcohol intake, I decided I would investigate the brown liquors, because historically they have not been so interesting to me. And to my dismay, I discovered that I really love them. Bourbon and rye are amazing." Among the drinks that were unveiled to his palate was the Sazerac, a 150-year-old, New Orleans-born cocktail which features rye, sugar, Peychaud's Bitters and a splash of absinthe. "This is what I drank in Berkeley: Old Fashioneds and Sazeracs almost exclusively." (Naming this reporter's two favorite cocktails in the world, I was all ears.) "I also like the Sidecar too. And the Blood and Sand." The latter is a mix of blended Scotch, orange juice, sweet vermouth and the Danish liquer Cherry Heering. It tastes better than it sounds.

The food matched the drinks in quality during his time rehearsing American Idiot. Mayer went to Chez Panisse, Alice Waters' famous and influential bistro, every week. Food guru Waters, it turns out, is a big "American Idiot" fan. (Not surprising, perhaps, as the members of Green Day are among Berkeley's leading citizens.) "She would always avail herself of us," recalled Mayer. "Little gifts would arrive at the table at key moments during meals. A plate of unbelievable heirloom tomatoes or some salad of baby lettuces that we hadn't ordered would appear, like a miracle."

| |

|

|

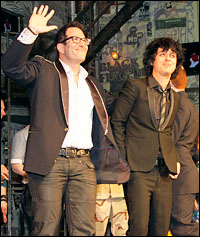

| Mayer with Billie Joe Armstrong | ||

| photo by Joseph Marzullo/WENN |

Mayer and Kushner have known each other since 1981, when they met at NYU. Like many stage pilots, Mayer trained as an actor before finding fame as a director, acting in many of Kushner's early plays, including A Bright Room Called Day. He also directed a third-year NYU graduate student production of Angels in America: Perestroika which played at the same time the mammoth play's first part, Angels in America: Millennium Approaches, bowed on Broadway. Mayer's work on that piece led to his big break: directing the national tour of Angels.

The two men will team up professionally for the first time in many years this coming spring, when Mayer directs Kushner's The Illusion. The adaptation of the famous Corneille work L'Illusion Comique will be part of Signature Theatre Company's season-long Off-Broadway celebration of Kushner's work.

That same NYU staging of Angels cemented another one of Mayer's longstanding professional friendships. At the time, a reporter from the Village Voice was researching an article about the show, interviewing members of the cast (which included Debra Messing and Ben Shenkman). The performers kept mentioning their director, Michael Mayer. "Is he from the D.C. area?" asked the curious journalist, whose name was Dick Scanlan. Scanlan would go on to write the book for the Broadway musical Thoroughly Modern Millie, which Mayer directed.

| |

|

|

| Michael Mayer | ||

| photo by Joseph Marzullo/WENN |

Was the Montgomery County Chorus an important cultural group, locally? "It was important to us, Robert," Mayer said with a laugh. "It's what we had. We were both gay, and not really out about it. This was 1976 when we first met. We were friendly, but not friends." The next year in chorus they became more friendly. Then, in the summer of 1978, the two young men performed together in West Side Story at Wildwood Summer Theatre in Rockville. "I was Action and he was Arab. So we were Jets together. And when you're a Jet, you're a Jet..."

After reconnecting in New York, Scanlan and Mayer vowed to meet each other every week at Elephant & Castle, a pub on Greenwich Avenue. (They still meet, though now they vary the restaurants.)

Scanlan and Mayer won't be reunited professionally this coming season, as the director and Kushner will. But that's fine. Mayer's schedule — as usual, since he scored in two consecutive, late-'90s Broadway hits, A View From the Bridge and Side Man — is busy. This winter, he'll bring his new spin on the Alan Jay Lerner-Burton Lane musical, On a Clear Day You Can See Forever, to the Vineyard Theatre in Manhattan. The piece had a public workshop-concert at Vassar College this summer as part of the New York Stage & Film season.

After two high-profile rock musicals — Spring Awakening and American Idiot — an old-school chestnut like Clear Day seems a radical right turn. ("I really do change it up quite a bit," he admitted.) But his interest in the 1965 show is no whim. "It's connected to Side Man," told Mayer, beginning the story. (Every show Mayer does, it seems — from Millie to The Illusion — is preceded by a long personal history.) "I was working at New York Stage & Film in 1996. We were doing Side Man up there. I brought with me a bunch of CDs. One of them was On a Clear Day, because it came out on CD that year or the year before. I got so excited, because it was something I listened to constantly during a period of time in my adolescence. There was something about that original cast recording.

| |

|

|

| Michael Mayer at Sardi's | ||

| photo by Joseph Marzullo/WENN |

Ettinger, it turned out, had just spoken to producer Elizabeth Williams, who was talking to Liza Lerner, the librettist-lyricist's daughter, about reviving that show. The designer recommended Mayer give them a call. "I pitched them the idea. That was 1997. It took a long time to find the right collaborator." That man turned out to be Peter Parnell, who was recommended by Tom Hulce, a producer of Spring Awakening and a friend of Mayer's. Last fall, the men presented a version of the musical to the Lane and Lerner estates. The estates gave the go-ahead.

The Vassar workship was a success, but beset by several family crises. The one that received the most attention involved star Anika Noni Rose, who had to leave the production for one performance due to a death in the family. Another cast member had to depart after learning their grandmother had died; and a third's mother experienced a medical emergency. Mayer, too, suffered a loss. His Aunt Sue — his mother's identical twin — died. Because of his responsibilities to the production, he was unable to get away.

"She was kind of like an Auntie Mame to me," he said, "took me to theatre all the time, took me to Paris for the first time." They remained in touch after he moved to Manhattan in 1980. "Every time she came to New York, she took me to Broadway shows that I would never have been able to afford on my own."

It was around that time that he first entered Sardi's. "I was with one of my friends from the NYU acting program," he remembered. "He had a friend from Michigan who was making his Broadway debut in a big musical. I remember meeting that actor and my friend in the bar downstairs. I felt like such an adult. I felt so inside."

(Robert Simonson is a special correspondent for Playbill.com whose work is also seen in the pages of Playbill magazine. Write him at [email protected].)

Highlights from American Idiot on Broadway:

Evan-Zimmerman-for-MurphyMade.jpg)