*

"I'm the downtown Neil," John Cameron Mitchell joked when referring to his busy schedule, which includes working on the Broadway premiere of his cult rock musical Hedwig and the Angry Inch, as well as writing a film, participating in a reading series at Joe's Pub and working on a sequel to Hedwig.

Neil is, of course, Neil Patrick Harris, who is starring on Broadway in Mitchell's musical as Hedwig, the East German transgender rock musician chasing after an ex-lover who plagiarized her songs.

Mitchell, who wrote the book of Hedwig, made his Broadway acting debut in Big River and has also performed in Six Degrees of Separation and The Secret Garden. Hedwig, which he wrote with composer Stephen Trask, opened Off-Broadway at the Jane Street Theatre in 1998 and ran for more than two years. Actors who have played Hedwig include Michael Cerveris, Ally Sheedy, Kevin Cahoon, Gene Dante, Anthony Rapp, Matt McGrath and Nick Garrison.

Mitchell went on to direct the 2001 film adaptation, which he also starred in and went on to win Best Director at the Sundance Film Festival and receive a Golden Globe nomination for Best Actor in a Musical or Comedy. Mitchell spoke with Playbill.com about the origin of Hedwig, its impact on the world and the excitement of "Hed-heads" who are attending the Broadway production.

Hedwig is finally taking a bow on Broadway, almost 20 years after she first opened Off-Broadway. Tell me about the process of creating the musical.

John Cameron Mitchell: At the very beginning, I wanted to create a theatre piece based on Plato's symposium story — the origin of love, which is a 2,500-year-old myth written by a guy — that used authentic rock-and-roll music as opposed to some of the stuff I'd heard in theatre, which just felt watered down a bit. It was originally about the character of Tommy, because he was closer to me, the general's son, and then I was looking for a composer for a while. I tend to take my time and do it right. Stephen Trask I met on an airplane, and eventually we started working together, and he encouraged me to focus more on this character of Hedwig, who was based on a babysitter of our family.

|

||

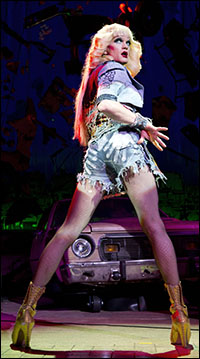

| John Cameron Mitchell as Hedwig |

And then we were Off-Broadway. Peter Askin built the Jane Street Theatre for us. An Off-Broadway theatre had to be built for us because no one else wanted us. All the normal people — the usual suspects of resident theatres — were not interested. It was just too weird. Peter was our guardian angel. And right away audiences were baffled. The theatregoing audiences who could afford the tickets were baffled. "What is this? Some kind of downtown, low class... what's going on? The music is so loud."

There were intriguing shows where many people didn't respond whatsoever, but there were always the minority of people who wouldn't stop coming. And then the press picked it up — Time Magazine, The New Yorker — and sort of saved us and made it the hip thing to see. And suddenly tons of celebrities would come. It was a huge success d'esteem. It was never a big money thing. And there was a bidding war for the movie. It was a special moment in time.

|

||

| Neil Patrick Harris in Hedwig and the Angry Inch. |

||

| Photo by Joseph Marzullo/WENN |

JCM: We had a strangely truncated rehearsal schedule because of Neil's TV show, and I don't know how he did it. I guess it's from doing all those Tonys shows. He can get things together so fast. Just the technical element, which tends to take other people much longer. He... thrills to the tasks that are technical — accent, voice training, finding his body, choreography, getting the singing right — all of that was done right before. He snatched time periods throughout the last six months.

We really only had three weeks to get from the beginning of real rehearsal to the first audience — including tech. That's never been done on Broadway before. I'd just never heard of that. Luckily, the show is less technically difficult; the lighting is the hardest thing. It was a really short tech. So the first audience was a surprisingly together show — and a psychotic audience. They were so supportive. I've never felt more confident about being ready, in a theatrical experience, ever.

It seems like if there are any world records left to break, Neil Patrick Harris will break them at some point in his life.

JCM: It's not always the most desirable one — I can rehearse that in two-and-a-half weeks! — but because of the Tony deadline, we had to do it. And he was game, and the show was ending. Also [to] avoid the post-partum and go straight into something — [to avoid being] bummed out by the end of nine years of a series. The best way to do it is jump into a show. He's having a blast.

He's got also more energy than I did. I want to make it easier for myself. He likes to make it harder and a challenge. He's like, "I want the heels higher. I want to have the microphone wired as opposed to unwired," which complicates choreography. In the day, I was like, "Lower the heels. Get rid of the cord."

It's fascinating that one of the most ubiquitous performers in America is playing a character that's described as "internationally ignored."

JCM: There's a great advantage to being the favorite secret thing, because it never gets ahead of itself. It never blows itself out of proportion. You don't get backlash when you're the underdog. And Hedwig is that. And in this case, there's an unusual situation where it's still Broadway; it's still a matter of a few thousand as opposed to millions. Broadway's still the fringe thing in terms of audiences, compared to Hollywood or TV. But it's really interesting to have someone who's, in the U.S. and U.K., a major star, embodying, in effect, a loser in many ways and bringing it to a larger audience of people who didn't expect to be moved by this bizarre story. We've got fans there, but we've also got all these new people because of Neil, who are being told, "It's okay to check this story out and realize, 'Wow. I can relate to a real marginalized person. And maybe it's because I felt that way, too.'" It's so interesting to hear about how the show became what it is. I love hearing about the actors that have played Hedwig.

JCM: I love that it's a true musical in that all kinds of people can interpret it in different ways. In Korea it's more of a mainstream thing. They had a reality show to find the new Hedwig. In San Francisco, they just did it with 12 Hedwigs — one for each song. I love that people feel free. In our publication of the script, we encourage people to feel free and put improv in certain moments and use the venue they're in and stuff like that. We've continued that tradition with our Broadway production, which I've custom-fit to explain why she's on Broadway today. I've updated some of the references and allowed Neil the leeway to mess with the audience and play with this moment in time, and he's brilliant at that.

|

||

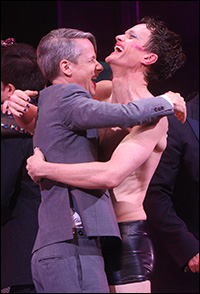

| Mitchell congratulates Harris on opening night. |

||

| photo by Joseph Marzullo/WENN |

JCM: We really didn't. We knew it was important to us and to our friends. When you try to make it important for too many people, it changes it. You lose your instincts and what you love about it. And, of course, that's the story of most of our pop culture — someone else trying to figure out what a million people want to see, which tends to blur your own instincts. It was always so odd, there was no way for it to be corrupted. When something is closer to the norm, it's easier for it to get corrupted, because you're like, "Oh, if you just shift it that way, then you can make that actor a giant star. It won't hurt it!" and then it sort of does and you're like, "Ugh." It's easy to stick to your guns when you're already a freak.

And it's wonderful that we're able to do it when shows like Spring Awakening or American Idiot or even Rent... It's interesting because I was auditioning for Rent when Hedwig was being developed, and I was offered the original role of Angel. I was flattered but I was like, "I'm already doing this drag role," plus I'm not very Puerto Rican. It was very flattering but I was like, "Thanks guys, but I've got to work on this other piece." And it would be weird to do both. God bless Rent. They went on to bring much love and emotion to the world. But we're not that.

But Rent [and] American Idiot made Broadway safe for us or let people know that we weren't quite as crazy as they thought. We're now here at the perfect time, with the music, with the drag — the issues are mainstream. There was never any talk of Hedwig going on Broadway since the century began. It's only later in the 2000s that people barely thought about it. It's the perfect time for it. The fans are ready for it. It's been all over the world. People with Hedwig tattoos come but also people who like "How I Met Your Mother" who didn't know, and they're all having a blast together.

Have you worked with Neil on developing the character of Hedwig? Or has he been working independently?

JCM: I wanted to let he and [director] Michael Mayer have their relationship. The last thing I would want is the original guy breathing down my neck. So I really stayed away. I certainly worked on the adaptation on the script. We did some back and forth on that. But I wanted to really let him find his Hedwig with his director. When I come in, I tend to want to direct. I can't help it. I withheld myself, knowing that I'm overenthusiastic, and came in at key moments near the last stages and said, "How can I make myself useful? Here are some ideas I have." At one point I was starting to give too many notes, and Michael was like, "Just pass them through me," and I said, "Of course! I'm sorry. I'm not directing." I get too excited. We've had a great relationship — Neil, Stephen, Michael and I — and the producer, David Binder, who did the original workshop, has been wonderful, too.

There's something really exciting about a show, especially a rock show, that provides new insight or new education to the audience.

JCM: It really is surprising. When we first did it at the Jane Street, the cross-section of audience was unexpected. There were the young, hip kids. Even the rockers were like, "What? Theatre? Lame." Then they were like, "Oh, a narrative!" I was like, "Look. This is a conventional narrative. It's a Broadway musical structure, even though it's a monologue, mostly. There's a beginning, middle and end, an 11 o'clock number. It's still very much Broadway, but the music's different, the subject matter's different."

The veterans — Betty Buckley, Patti LuPone, Anne Meara, Bea Arthur — would all come and be in tears. Charlotte Rae is the biggest Hedwig fan. And they're not known as punk rock bonafides. They were just feeling it. And then you'd have the Lou Reed, the David Bowie, the Marilyn Manson, sitting next to Barry Manilow, and all loving it. And we were like, "Yes!" We're bringing together everyone we love and the kind of aesthetics which ultimately are just about doing it right and doing it with soul. And doing it [with] multiple influences in mind and not shirking any of them. Making sure we have the drag queens, too, are like, "Yes." That was very important to me. I was most nervous when I saw the real drag legends come in, like, "Oh, f*ck. I'm not a real drag queen." And they were like, "Yes." Now there will be even more people coming to the theatre and hopefully saying, "Yes."

There will always be some people who are like, "Wait a minute. It's not like it was." Of course, nothing's like it was. We're all doomed to loving what we saw at 20 years old more than anything else. But it's time for new memories and a new way, and Hedwig's story is still relevant. There's nothing dated about her feelings.

It's exciting to think about all the progress that has been made in the last decade or so with regards to gender identification and equality.

JCM: It's interesting. Hedwig has never been representing anybody but herself. She's not a trans activist. She's not a gay rights [activist]. She's had her own accidents of fate that were connected to violence, misuse of power, and she's done her best with it. And that's the universal story. She doesn't stand for anyone else and would find it outrageous to say she is an example. But when she sings to all the strange rock and rollers in "Midnight Radio" and sings, "Hold onto each other," she's singing it to the audience. Neil — I love how he does this. He's saying, "We're all in this together." And rock and roll and theatre and drag are all the same thing. They're ways to remind yourself that you're not alone.

(Carey Purcell is the Features Editor of Playbill.com. Her work appears in the news, feature and video sections of Playbill.com. Follow her on Twitter @PlaybillCarey.)