To look at his best-known credits, Minchin's name might not be the first to come to mind when considering who might be the proper songwriter for a musical based on Roald Dahl's children's novel about a schoolgirl with magical powers. The Australian comedian, songwriter, actor and musician has traversed some pretty non-PG territory — he played a drug-fueled rock star on the Showtime series "Californication" and Judas Iscariot in the U.K. arena tour of Jesus Christ Superstar, and penned songs that bluntly address hot topics such as sex scandals within the Catholic church ("The Pope Song"), religion ("Thank You God") and prejudice ("Cont"), each number subverting expectations of the listeners by the final note.

Minchin's ability to deliver these songs with a cheeky charm — a disarmingly innocent directness — made him a perfect collaborator for book writer Dennis Kelly on the musical that took London by storm.

Playbill.com spoke with Minchin about his inspirations, his children, his love of Dahl and his singular world view that shapes the world of Matilda.

Was Dahl a big part of your childhood?

Tim Minchin: Yeah — huge. At varying ages I suppose I read them all, and I didn't read "Matilda" as a kid because it was very late [in my childhood]. Although I'm always slightly loathe to attribute things to influences because it's always — I think it's a simplification of the truth — but he was a big influence on me. And I really loved his poetry as well, people forget about "Revolting Rhymes" and "Dirty Beasts." I think I always got a huge thrill out of good rhyme and meter, you know? Something about well-constructed poetry makes my brain fizz, and I think that comes very early on, and Dahl was certainly a part of that. Huge fan.

You mentioned you were a bit older when "Matilda" was published. Had you read it prior to the start of the musical?

TM: Yeah, I definitely had — it just wasn't a part of my childhood because by the time he wrote "Matilda" I was 13 or something. But I read it subsequently — I always read children's books and still do. I read it probably when one of my sisters got it, or something. I guess I read it in my teens. Then, in my early 20s, I asked the Dahl estate about the rights for it because I thought it would make a good musical, and then totally coincidentally it came back to me. You had an inspiration for the musical prior to the Royal Shakespeare Company production?

TM: Well, I was still in Perth and I was writing children's theatre with a little theatre company. It was at a period when I was acting one week, playing in bands the next, and doing all the things I now do, but on a much smaller scale. I would get these projects, and to write a score for one of these shows, it takes four weeks or something. I'd get paid a thousand bucks and then they'd [run] a couple of weeks, and they'd be done. So that was the sort of scale I was thinking about. My intention was to gain what permission I had to get to write a small show for a local production. I was so thinking on that [small] scale that it wouldn't have crossed my mind they would say, "Oh you could send us a score and we'll consider it..." Being someone who can't read or write [music] — the very word "score" scared me away at that stage, 10, 12, 13 years ago. That was enough to make me just move on to the next project.

That story's become a bit apocryphal, and people say, "Oh he'd been trying to write Matilda for 10 years and then the RSC [Royal Shakespeare Company]…" That's not the case at all. I just wrote one e-mail. But it remains the only time I've ever written an email to anyone about the rights to the book. So, I guess I thought it was a good idea, and then when [Matilda director] Matthew Warchus got me into a meeting, and asked me if I'd heard of "Matilda" cause they were considering me to write songs for a musical version. I said, "You're f***ing joking! Awesome!"

| |

|

|

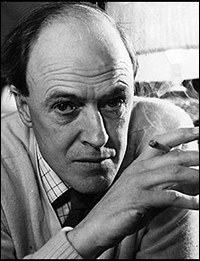

| Roald Dahl |

TM: I had written a lot of music for theatre on a small scale in my life. I never dreamed I would get to write a show that'd become what this has become. But I had written music for theatre long before I became a comedian. In fact, even my comedy is very theatrical in its songwriting style, isn't it? It's not pop parody. It's just using theatrical sort of devices, musical theatre, to get a point across. So, in a way I don't think the job is different. There's a sort of almost tacit assumption that if you swear, or have anger, or at least express anger about things — if you say, "F*** the Pope," or can call God a "c***" in a song, that means you have some sort of compulsions, Tourette Syndrome-like compulsions, as opposed to [realizing] they're clearly devices in those songs.

In both cases they're placed to make a point. In the case of "The Pope Song," to say something outrageous, and then reverse-engineer a kind of trap to make people think about what they find ethical. [Here's a video of the song; warning — it contains material that may offend some listeners.] And you know, my comedy's not a spasm — it's designed. That's the great thing about the Royal Shakespeare Company and other subsidized theatre groups who aren't totally profit-driven — they can take risks, and every now and then those risks can really pay off. The risk was that I didn't know whether I was engaged in theatre and the telling of stories. As it turns out, I am and always have been. But they sat down, and talked to me, and were obviously convinced by my rants on how I think this story should be told. I neither had to try and be dark or pull back from darkness, because I just felt like I was bathed in Dahl as a child — marinated in Dahl — and so I didn't even go back and read any of his books again or go and research him. I just thought, "Oh yeah, I know what Dahl's like, Dahl's like — well he's like me." I mean, he's a genius and I'm an idiot, but in terms of his sort of humor, I just sort of thought, "Oh, well, he loves funny words, and it's a bit dark, and it's funny, and I'll just have a crack at." All I did was, I sat down with the script adaptation and wrote what I thought was needed at the time, you know. And I had no problem not swearing, just like I don't have a problem not swearing when I'm parenting or talking to a journalist on the phone!

|

||

| Bertie Carvel in Matilda The Musical. |

||

| Photo by Manuel Harlan |

TM: They like it. They were too young, really, during the writing process [to try material on]. Violet has just got to the age where I think it's a good age to see it. She just turned six and is starting to enjoy it. But I guess the music in various forms has been a big part of her life. So it's completely pedestrian to her. She's got a lot of friends at school who are obsessed by the songs and can sing the whole thing through. And so Violet is one of the least interested people I know. But that's fine. She's seen the show a few times and she gets very worried by it. She's an interesting and emotionally quite sensitive little kid, so she gets this stricken look on her face the whole time [at the show]. I said to her at interval when I took her on her sixth birthday — which she requested — I said, "Are you not enjoying this? You know you don't have to stay, baby." And she said, "I do like it. It's just very worrying." And she's just worried, you know, Mr. Wormwood is really mean. And I think that's appropriate. As a six-year-old, you should be a bit worried, and you should be leaving the theatre overjoyed and full of excitement because the ending is happy and all that. But yeah, I think six-year-olds and twelve-year-olds should be asking questions about revenge and cruelty, and it's fine. That's why Dahl's brilliant because it's all there but it's treated sort of lightly.

Was that something that guided you as you wrote, this notion of cruelty handled in a way that children can witness it without being brutalized by it?

TM: Yeah, I think so. It's interesting because although I had this background [with] Dahl it was [book writer Dennis Kelly's] adaptation that I was writing for, and I was very much guided by him. I think I reacted quite instinctively, and I know Dennis did. I think overthinking is something that musical theatre makers do a lot. I can't speak for other musical theatre makers, I'm just trying to say something about my process, but I think there is a risk, probably. I'm not very experienced, but there is a risk with musical theatre because it takes so much work, and they're so rarely hits, that when you're in the business of making one, you can really try and just figure out what the formulas are. Those are naiveties to Dennis' and my approach, I think, [that] probably helped us in hindsight. Neither of us were loaded up with any particular investment to it. We had a little commission, we really wanted it to be great, and we reacted to the story. What does the protagonist need to be doing now? How do we make it funny, and entertaining, and snappy, and how do we stop it lulling? How do we make it both silly and sincere without the sincerity being saccharine? All those sort of more basic sort of storytelling concerns. Of all the doubts about myself, which of course are many and varied about my credentials to do a project like this, I never even considered that I didn't know what Dahl was. It just didn't cross my mind that I should worry because Dahl is Dahl. Dahl's my childhood, I mean I read all the books before I read anything.

Was the Dahl estate actively involved in this? Did they provide guideposts along the way? Or were the totally hands off?

TM: A couple of people from the estate were involved, Dominic Gregory [director of Dahl & Dahl Limited] being the primary one. He would come in and give notes periodically. But you always have to try and get a good balance between taking notes from something like the estate of the source text, or producers, obviously. You don't want to bury your head in the sand and ignore the experience of producers and estates, but you need to – sort of like what I was saying a minute ago about process — you just need to unclutter. All you can do is be creative and try to tell a story based on the resources you have, and you've got to be really careful. But the Dahl's were absolutely brilliant. You know they were nervous, as they are with all projects that are licensed, because they want Dahl's tone and reputation to remain as it is. There were times when we had to sort of fight for things, and times when we took their advice, and they fought and won, but it was certainly not a heavy-handed thing.

| |

|

|

| Dennis Kelly |

TM: I read the script, and sat down and played the piano for a bit, which is what I do. I just play and play and play, and half the time I'm just playing blues and mucking around and wasting time, and eventually I'll sort of stumble toward some kind of audio color. And with Matilda, the real thing that Dennis did — which had nothing to do with Dahl except obviously Dennis was aping Dahl's style of storytelling — was that Dennis wrote a subplot that doesn't exist in the original story at all. [This] backstory, [he] drags it out across the musical in a very very clever magical way that solves the problem of the sort of children's book reveal that Matilda has. The musical is a lot more mature than the book, in that it suits adults as much as it suits children, and that's actually the thing we got right somehow. I think that's the thing we've stumbled on, is that it's genuinely a piece of theatre that a 65-year-old truck driver will enjoy as much as a six-year-old girl. But Dennis' acrobat and escapologist subplot was actually the first thing I went to, because it had a circusy old-worldy thing, and so I wrote that sort of circus theme first because it was just the thing that came easiest.

The second thing I wrote was "When I Grow Up," because again, before I get into the detail of the story, I'm thinking [about] what the character's going to sing, how are we going to express what that characters worldview is, and all those chores that musicals have to do. I just wanted to write a song that captured the vibe of the show, and wasn't to be sung by anyone one character but was a chorus number. "When I Grow Up" is sort of the song that people remember most now because it does float above the narrative a bit. It just places a sort of blanket of un-sentimental sentimentality across it. And it is also structurally, harmonically, exactly the same as "The Naughty Song," so eventually I took those chords and that pace, and pretty much the same feel, and re-wrote the melody and lyric,s and put them in the hands of Matilda, so by the time it comes along it's harmonically familiar even though you don't consciously know the derivative of it.

The vocal harmonies in that song are so beautiful. It's such a fantastic song.

"Awww, thanks. I like it. I'm still fond of it. It's pretty dominant in my life now, I don't mind not hearing it for a while! I'm proud of "When I Grow Up" because it does what I want to do as a songwriter. In all my stuff, not the sort of harder-edge satire, but even in you know "Not Perfect" or "You Grow On Me Like A Tumor" or "Beauty," one of my not so clearly funny songs, is to find an interesting way to express a common sentiment — and "When I Grow Up" has that kind of honesty without being twee. It's kind of innocent... Anyway, yeah, we could bang on about that but that'd be kind of boring.

Regarding Miss Trunchbull, did you know you were writing it for a man to play the role, or did that come out much later in the process?

TM: "I was, how can I say, I was writing it for a man to play rather stubbornly because I thought it should be played by a man. So I just wrote it with that in mind without really consulting anyone. But, it wouldn't have mattered, because either way her kind of way of being is a certain thing. So, if it was a woman we might've had to change the keys. But she wouldn’t sing floaty notes or anything because that wouldn't be right for her character."

You previously said that you have to trust your gut and not second guess when writing. There's a lot of momentum behind the show as it hits New York, were you tempted to make tweaks for New York, or did you have to say, "No, let it play."

TM: Well the one thing about working with Matthew Warchus is that he leaves no stone left unturned, so how much we were going to take the American audience into account was addressed and continued to be addressed. There was a decision about whether it should be English or American, and I think it would sustain itself perfectly well everyone did American accents, there's nothing inherently parochial about the story. However, there is an English-ness to it that is best served by staying English, so that decision was made. [There are] about four changes in the whole musical. Like the start of [the song] "Bruce," "I can see that a slice is" and just because of the accent and the kids' mouths, we changed it to "I know a slice…" We believe in the show. It's got very dense lyrics, and if you un-densify my lyrics it's not my thing anymore. The lyrics are so dense that the English audiences miss half of them - that's the nature of the theatre, you always miss half of everything [because] your eye is attracted by this and that. It's an incredibly sensory or sensorially dense experience going to a musical. We want is our audiences to have the best time. So if there's a moment that used to get a laugh in England and it doesn’'t get a laugh in America consistently over several weeks of shows, we need to examine and go, "Oh it's a pity they don't laugh there because that's funny. Is there a way we can say that, a phrase or a word?." We are trying to maintain the artistic integrity of it entirely, but we're not being obtuse about. We're not being stubborn. If we think there's a better way to help this different audience with the same stuff. We're not being purists to the extent that we refuse to change a single word simply because we think we're untouchable or something.

Check out this video about Matilda's journey to the stage.