*

Dramatist Doug Wright has written about real people before: Broken Long Island socialites Edie and Edith Beale in the musical Grey Gardens, for example, and the singular Charlotte von Mahlsdorf, a German transvestite who survived the Nazis and the communists, in I Am My Own Wife, for which Wright won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama and the 2004 Tony Award for Best Play. But never has a work by Wright been so close to home as it is with the fact-based Hands on a Hardbody, the tale of disparate and desperate Texans who participate in an endurance contest — last man standing with their hands on a Nissan "hardbody" pickup truck wins the vehicle. Wright, a Dallas native, "got" the people and setting of the story, inspired by the 1997 film documentary of the same name. Wright shared with Playbill.com some of the challenges and joys of creating the populist ensemble musical, which has music by Trey Anastasio (of Phish fame) and Amanda Green, and lyrics by Green (High Fidelity).

The Nissan dealership in the film "Hands on a Hardbody" is located in Longview, TX, somewhere between Shreveport and Dallas. You're a Dallas native. How much of your attraction to this project was its Texas setting? Do you think if it had been set in North Dakota you would have been drawn to it?

Doug Wright: For a long time, I've hankered for a vehicle that would allow me to write about my home state. I found the characters in S. R. Bindler's documentary film immediately identifiable; even though I grew up in the relative comfort of the Dallas suburbs, I felt as if I knew them all: Benny Perkins [played by Hunter Foster], the backwoods sage; Kelli Mangrum [played by Allison Case], the feisty tom-boy with ambitions larger than the landscape can contain; Norma Valverde [played by Keala Settle], the fervent believer; and J.D. Drew [played by Keith Carradine], the spirited good-old boy with the infectious grin. What a wonderful, lovable, idiosyncratic gallery; I couldn't wait to try and capture them on the page.

| |

|

|

| Jay Armstrong Johnson, Allison Case and Hunter Foster in the 2012 La Jolla Playhouse production. | ||

| photo by Kevin Berne |

DW: Texans are born raconteurs, and they're compulsively friendly. Hands on a Hardbody is the story of a die-hard, even cut-throat competition, but ironically, the competitors in the story wind up becoming friends. That, I think, is indicative of something innate in the Texas character; our politics may be crazy sometimes, but our generosity of spirit is contagious.

Remind me — how deep is your history in Texas? Are there generations of Texas Wrights? And were trucks in your DNA?

DW: My grandparents and cousins lived in Lubbock, TX, and I grew up in the suburbs of Dallas. I was a theatre kid; I've never driven a truck in my life. We had an old 1969 dark blue Lincoln Continental with "suicide doors" that I used to drive to high school; her name was Bessie. But there was always something seductive about the trucks that would lumber through the neighborhood or on the highway; even in big city Dallas, folks still wear boots and cowboy hats without irony. A truck is a symbol of down-home, no-frills authenticity.

When did you leave Texas? And you ever miss the barbecue?

DW: I left to go to college, but still return a few times a year to visit family. And I do miss the barbecue; Peggy Sue's and Sonny Bryan's are my favorites.

| |

|

|

| Allison Case in the La Jolla production. | ||

| Photo by Kevin Berne |

DW: Early on, Amanda and I got out bulletin boards and notecards and started outlining our story. Often, she'd ask me to write monologues for characters that she would later turn into lyrics. Together, we wanted to be intimately familiar with every single beat in each character's journey. I've never worked so painstakingly with a lyricist before; she borrowed turns of phrase from me, and vice versa; I was only too happy to steal her jokes. I think we both felt responsible for the show's architecture, and so we built it together.

When Trey came aboard, he informed our work in astonishing ways. His knowledge of music is so vast — from the Delta blues to alt country to pure Americana and yes, even show tunes — that his musical impulses enriched our characters. And he's a real stickler for the truth; if details in my text didn't seem accurate — like the mention of a particular Marine base, for example — he challenged me to get it right. I'm so grateful to him for that.

How did this project and collaboration come to be? What are the seeds of Hands on a Hardbody?

DW: When I was living in Brooklyn, I rented the film one homesick night and fell hopelessly in love with it. I knew it could be a musical; these were characters whose hearts and hopes were so big they almost required songs. That said, I'm merely a playwright; I have a terrible sense of rhythm and I'm essentially tone deaf. I knew I'd need a formidable musical collaborator.

Amanda had approached me some years before about working together, but we'd been unable to find suitable material. In my soul, I knew she had both the hilarious wit and the stinging sense of pathos to bring Hands on a Hardbody to life. I sent her the film and asked her to watch it. She became as infatuated as I was, and together we flew to Los Angeles to meet the filmmaker and option the rights.

Later, she asked Trey to come onboard and compose the score with her. In no time at all, it was an obsession for him, too. All three of us have adopted it with a fanatical zeal; Amanda and Trey walled up for almost ten days in the country to pound out songs together. They'd email tunes to me; I'd send back book scenes. We'd get together at Amanda's apartment and pore over the script endlessly, reading and singing aloud. We've all poured our blood into this piece; it's a bona fide labor of love for each one of us.

| |

|

|

| Wright in early rehearsal for the show. | ||

| Photo by Terri Rippee |

DW: Amanda and I knew there were at least eight figures in the documentary whose stories we wanted to dramatize. Unfortunately, we had no way to reach them. Their full names weren't always used in the movie, and 15 years had passed since it was filmed.

Somewhat desperately, we sent the DVD to a private detective in East Texas, so he could locate them for us. Once we got a list of addresses, we hopped a plane to Dallas, drove to Longview, and started knocking on doors. Our purpose was twofold: to secure the cooperation of the contestants, and to interview them about their experience.

It was a hilarious, exhilarating trip; we found ourselves on porches in tiny towns like Gladewater, TX, saying chirpily, "Hi, we're Broadway writers from New York and we'd like to put you in a show, all because you entered a crazy contest 15 years ago at the local Nissan dealership!" Folks were shocked, but gracious. J.D. and his wife Virginia Drew invited us in for egg salad, and Benny Perkins took us on a night-time bar crawl through Longview that neither Amanda nor I will ever forget.

We've kept in touch with all of them. Virginia Drew just sent me a new batch of her home-made jalapeno jelly, and every major Christian holiday, I get a lovely note from Norma Valverde. J.D. Drew even built me a birdhouse, with a bent Texas license plate for a roof. And our whole cast at the Brooks Atkinson enjoys Facebook friendship with Benny Perkins.

| |

|

|

| Dale Soules, Kathleen Elizabeth Monteleone and Jon Rua in La Jolla. | ||

| photo by Kevin Berne |

DW: The musical was inspired by the documentary; it's not wholly faithful to it. The demands of the stage are very different. As dramatists, we knew we needed to serve our own story and our chosen themes first. We saw the contest as a metaphor for the country in this particular historical moment; it tackles issues very present in the current culture, from the war over immigration policy to income equality and the slow erasure of the working class. We try to be true to the essential spirit of both the film and its subjects, but — first and foremost — we wanted to serve our own story.

Were there characters from the film that did not make into the musical? Are there composites or conflated characters? Are there any wholly original Doug Wright-created folks?

DW: "Yes" to all of the above. Some characters are conflated, and others — particularly the dealership itself, which we have re-christened Floyd King Nissan, and its two proprietors Mike Ferris [played by Jim Newman] and Cindy Barnes [played by Connie Ray] are very much our own.

| |

|

|

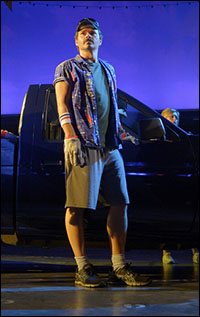

| Hunter Foster in Hands on a Hardbody. | ||

| Photo by Kevin Berne |

DW: Very much so. In fact, that provides much of the fodder for our story. When you see the show, you'll hopefully notice how we tackle each of those points in our narrative. Frivolous as the contest may sound, it was unbelievably grueling; there's no question that for the contestants it was both exciting and traumatic.

What did you learn in t La Jolla Playhouse during the world premiere in 2012, and what work did you set out to do before Broadway?

DW: La Jolla was so very generous to us, and we learned so much. Following our run there, we dramatically restructured our whole first act. [Choreographer] Sergio Trujillo joined our creative team. Our set designer Christine Jones re-thought the visual world of the show in a profound, really gratifying way. To test-fly changes in the book and in the score, we did another three-week workshop after completing the West Coast run. So the show has changed substantially. The only thing that's remained constant? Our glorious cast.

What have you learned in previews on Broadway?

DW: Plenty. In one nail-biting week, we cut two songs, and in a delirious spasm of inspiration, Amanda, Trey and I huddled in a dressing room upstairs at the Brooks Atkinson, and I watched in amazement as they wrote a new one on the fly; it's now one of my favorite numbers in the show. I've tweaked lines endlessly. Our cast has been very gracious and accommodated all of the new material with utter professionalism.

The people of the film offer choice phrases and observations, like sagacious Benny, who says, "It's a human drama thing, it's not just a competition, it's not just a contest, it's human drama, it's human life happening." There's a line about "tryers." Is this gold for a dramatist? Did you lift lines, wholesale, from the film?

DW: Yes, many lines come straight from the film. Amanda's been particularly adept at integrating some of Benny's bon mots into lyrics. "Hunt with the Big Dogs" is our first-act closer, and it's a phrase borne of the man himself.

| |

|

|

| Kathleen Elizabeth Monteleone and Jim Newman in the La Jolla production. | ||

| Photo by Kevin Berne |

DW: Everyone wants opportunity. For people in rural areas, a truck can be a true vehicle for change, in the most literal way. In the last few years, we've seen the face of opportunity change in America, as the rich get richer and the middle class gets squeezed....as manufacturers uproot themselves to move overseas...as obscure financial instruments and popular culture have become our chief products for export instead of actual, tangible things like cars, computers and appliances. The American Dream is predicated on the promise of equal opportunity, but increasingly it seems, the game is rigged. We're an almost wholly corporate culture now. But the yearning for opportunity is still innate in our character; how do we sate it?

I got the sense from the film that these "characters" formed an odd kind of family by the end of their 70-something-hour endurance ordeal, supporting each other, caring for each other — even though two days earlier they were strangers. Do you see them as a family? Did that idea come up in discussions with your collaborators?

DW: Of course. It's one of the most touching aspects of Bindler's film, and (I hope) our musical as well.

We long to see love stories in musicals. If not romantic love, I sensed bonds and affection in the film. Is there a complicated flow chart in your files that maps out the relationships of all ten contestants, and what each means to the other?

DW: In some desk drawer, I'm sure I'll still have those infamous, scribbled notecards I made with Amanda. We did chart the relationships in the story with painstaking exactitude. But the musical's premise was on our side; enduring something extreme together bonds our characters in a surprisingly short time, like soldiers in a foxhole. The contest lasts only four days, but significant relationships get formed, evolve, and even break apart in that time.

| |

|

|

| Director Neil Pepe and co-composer Trey Anastasio in rehearsal. | ||

| photo by Terri Rippee |

DW: On a rudimentary level, theatre should be about magic. It should make the intransigent move, and the earthbound soar. It should make the mundane compelling, and it should reinvent our notion of space and time. Ideally, it should accomplish all of that with deceptive simplicity. Amanda and I met with several potential collaborators who said, "The concept is too static." We knew they weren't the right people for us. We needed folks like Neil [Pepe] and Sergio [Trujillo]; when we warned them, "It's a show about people who stand around at truck," their eyes lit up with the absurdity of the challenge. They passed the test, and passed it beautifully. I don't want to say much more; I want to preserve a few surprises!

If you entered an endurance contest like the one in the film, how long would you last?

DW: Writing a Broadway musical is (surely) an endurance contest. So far, I've weathered this one for about the last five years.

What's next for you as a dramatist? Can you share any upcoming projects?

DW: I have commissions for the producer David Stone, and for the Atlantic Theater Company. As soon as our truck hits the open road, I'll be buckling down to write again.

(Kenneth Jones is managing editor of Playbill.com. Follow him on Twitter @PlaybillKenneth.)

Here's video produced by La Jolla Playhouse, where Hands on a Hardbody had a 2012 tryout: