*

Working [Masterworks Broadway].

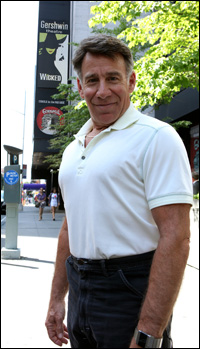

It is impossible to discuss the travails of Working — arguably Broadway's most spectacular failure of the late 1970s — without first talking about Stephen Schwartz, who spearheaded the enterprise. "Spearheaded" meaning that he adapted the non-fiction book by Studs Terkel and directed, in addition to writing a significant portion of the score.

Current-day audiences know Schwartz, mostly, as composer/lyricist of Wicked. The show, which has been drawing them in since 2003, did not much please the critics or the awards-voters, no; but that slight turns out not to have hurt the enterprise all that much. Yes, the creators and producers and investors of The Producers, Hairspray, Avenue Q, and Spring Awakening can all proudly point to their sterling reviews and their sterling Tony Awards, and I don't imagine one of them would care to trade shows. Still, I suppose there comes an occasional dreary and drab morning when they wake up and think, "Wicked grossed $2 million last week, how long before I can get a Broadway revival of my show? And how much is 2 percent of two million a week, anyway?"

|

||

| Stephen Schwartz |

||

| photo by Jeremy Daniel |

Next came The Magic Show, as empty a musical as any that ever ran over 1,900 performances. The show's gimmick — magic from Doug Henning, who was briefly a celebrity magician — didn't call for much in the way of songs or story, and that's what the authors successfully provided. When the long-running Godspell moved to Broadway in 1976, Schwartz suddenly had three hit musicals running simultaneously. (What would have been the fourth didn't make it: The Baker's Wife underwent a long and vitriolic pre-Broadway tryout before folding ignominiously just before Godspell moved to the Broadhurst.)

Visit PlaybillStore.com to view theatre-related recordings for sale.

|

||

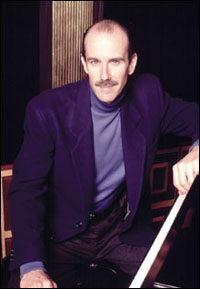

| Craig Carnelia |

A musical featuring a group of disparate characters telling their hopes and dreams was not exactly novel; the biggest thing to hit town in years was just then playing over at the Shubert, namely A Chorus Line. But Working was something like A Chorus Line without Michael Bennett. Without Bennett as director/producer, whipping the material (and his writers) into shape — but also without Bennett as a character within the show. Zach is, of course, Bennett; the characters are telling their stories within the framework of the audition for Zach. Working had no framework to speak of; lots of characters with lots of stories — some compellingly told — but there was nothing that they were trying to actively "get" (like a job in a musical).

In Working, you had a bunch of actors come on singing the opening number, and then — what? One song or speech after another, coming from one character after another. Compounding the problem was the doubling; everybody played several roles, which meant that you couldn't latch onto Sheila — say — and follow her through the process of the show. It didn't take long for the audience to realize, oh, there's nothing goin' on. There wasn't.

|

||

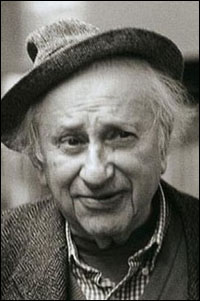

| Studs Terkel |

Enough of that. We now have the original Broadway cast album, from Masterworks Broadway. (An out-of-print version of the CD, with some variable additional material, was briefly released by Fynsworth Alley back in 2001.) The score received especially rough handling: Clive Barnes in the Post called the songs feeble and complained of "the bland sound of Muzak," while the head Times critic at the time — anyone remember Richard Eder? — found them trite, sentimental, banal and deadly. The cast recording, released long after the closing, demonstrates that this is an unfair assessment. Within the show, many of the "characters" related their stories in dialogue alone; there were only 15 songs amidst lots of talking, and this in itself made the score seem insubstantial. Most critically, the first song (following the opening number) was poor; the second thoughtful-but-mild; and the next was one of those cutesy, synthetic items — about a newsboy whose papers go "boing" in the bushes — that aim to be showstoppers but fall way short. When the show finally got around to several strong numbers, the improvement was like momentary lightning flashes in a dull, dry evening.

Visit PlaybillStore.com to view theatre-related recordings for sale.

|

||

| Lynne Thigpen |

Four of the songs — including two of the show's highlights — come from Craig Carnelia, another songwriter who has for some reason never gotten the break his talent deserves. (His two produced Broadway musicals were quick failures, Is There Life after High School? and Sweet Smell of Success.) "Just a Housewife" is a paean to the women who choose to stay home and raise kids, a simple-sounding anthem that turns into something thoroughly rousing. It is sung by Susan Bigelow; as I recall, she was a last-minute replacement — was it during previews? — for D'Jamin Bartlett.

Carnelia's other winner is perhaps the finest song in the show, dramatically. "Joe," it's called, taken from Terkel's interview with a retiree (played by 70-year-old Arny Freeman — who himself had discussed his career as an actor in Terkel's original book). The song seems to be almost an afterthought, some old guy sitting musing over his empty, unimportant life. But at several moments, enthusiasm over past memories bursts through — only to be instantly extinguished. Otherwise he remains sitting alone, watching the clock. In Carnelia's hands, you forget about the lyricist altogether; this is a real guy, talking about his real life, and giving us a true and honest portrait in the manner of Terkel's book. Whereas most of Working turned the real people into mere stage people.

|

||

| Lenora Nemetz |

Let us point out in passing that the oddest part of the evening in retrospect — and at the time to those of us who already knew Patti LuPone from her auspicious performance in the title role of Schwartz's The Baker's Wife — was her presence here without a song. LuPone's dialogue within the opening number is clearly identifiable on the CD — "one hundred dollars an hour, whatever you want," says the Hooker — and she is presumably adding vocal fuel to the ensemble numbers. But that's it for her. Readers in search of curiosities will note that the cast also includes Bob Gunton, who is given a poor song about being a dad (which doesn't seem to have much to do with working or Working). LuPone and Gunton would within the year be playing Ma and Pa Peron in another, more successful tuner. Also on hand, singing James Taylor's "Brother Trucker," is Joe Mantegna, who is better known for his dramatic work. Visit PlaybillStore.com to view theatre-related recordings for sale.

(Steven Suskin is author of "Show Tunes" as well as "The Sound of Broadway Music: A Book of Orchestrators and Orchestrations," "Second Act Trouble," the "Broadway Yearbook" series and the "Opening Night on Broadway" books. He also pens Playbill.com's Book Shelf and DVD Shelf columns. He can be reached at [email protected].)