A Time for Singing [Kritzerland]

It is always cause to celebrate when one of those long-lost, long out-of-print Broadway musicals finally make it to CD. There are a dwindling number of such titles; in most cases, they were originally recorded by labels that did not specialize in the field. Thus, the rights are often unnecessarily entangled, the contracts missing, etc. Kritzerland, the label run by Bruce Kimmel, has once again come to the rescue by releasing a limited edition pressing of the 1966 musical, A Time for Singing.

This will surely cheer up cast album aficionados, who have long sought the old Warner Brothers LP. There is some interesting material here; even a subpar 1960s musical can sound mighty tuneful when compared to some of what we hear nowadays. But the score is not very good, and neither was the show.

It wasn't the worst show of the season; Pousse Café, Duke Ellington's transformation of "The Blue Angel" to New Orleans, is a legendary flop. But A Time for Singing was unanimously panned by the critics. The Times called it "insipid," while the Post said the show "lay under a pall of heavy dullness," and the Journal complained of an "overlay of banality," noting that the authors had taken this vigorous tale of Welsh coalminers and seemed to place it "somewhere between Brooklyn and the Ozarks." The show opened at the Broadway—sandwiched between the openings of the cheerier It's a Bird...It's a Plane...It's Superman and Mame—and closed after five empty weeks.

Even so, parts of the score are pleasing, much is interesting, and it is professionally outfitted by orchestrator Don Walker. There are certainly plenty of full-voiced vocals, and that counts for something. The show was based on a popular 1939 novel, Richard Llewellyn's "How Green Was My Valley." This was in 1941 turned into a beloved Hollywood classic of the same title; it took that year's Best Picture Oscar against such contenders as "Citizen Kane" and "The Maltese Falcon." Thus, this was a case of a musical based on an honored and well-remembered property, which can be a double-edged sword. In this case, the first string critics all seemed to go in ready to cry once more at this tale of coal miners facing a strike capped by a mining disaster. They were familiar enough with the property to point out changes in the narrative, and uniformly disappointed by what they saw as mundane, formula writing.

One wonders what the authors and their producer—Alexander H. Cohen—were thinking. Gerald Freedman had thus far directed only one Broadway musical, the unsuccessful Gay Life in 1961; he had never written book or lyrics for a Broadway musical. Broadway has had at least a couple of accomplished librettist/lyricist/directors, namely Coward and Cohan, but they were special talents. Hammerstein was capable of filling three hats, yes, and Harburg tried it once with negligible results. But Gerald Freedman?

One can only guess that they were hoping for a name director, presumably Jerome Robbins. (Freedman was assistant director to Robbins on Bells Are Ringing, West Side Story and Gypsy.) Perhaps Robbins strung them along until such time as they had no choice but to go ahead with the only director they could get. This is mere conjecture, but there must have been some compelling reason for Cohen and his investors to entrust the enterprise to a novice. And who knows, Freedman might have done a better job as director if he wasn't busy trying to rewrite the book and lyrics. (Let us add that Freedman did a memorable and masterful job as director of the 1976 musical, The Robber Bridegroom.) Gower Champion was called in during the tryout to doctor A Time for Singing, but the patient needed more than a few bandages.

Also a first-timer was John Morris, who wrote the music and collaborated with Freedman on book and lyrics. Morris was well known around town as a tiptop dance arranger and conductor, with Bells Are Ringing, Bye Bye Birdie and Wildcat among his credits. But it seems like it was quite a gamble to have everything riding on Freedman and Morris, and the gamble did not pay off.

(Morris might well have gone on from A Time for Singing to write more Broadway musicals, except for the quirks of fate. When Mel Brooks started work on his 1968 film "The Producers," he drafted Morris—who had been on the music staff of Brooks' two Broadway musicals, Shinbone Alley and All American—as composer.)

The recording is not helped by the two leading performances. Ivor Emmanuel, as the poverty-stricken preacher, is positively dour. He has a strong singing voice but doesn't demonstrate much charm. Even when he sings a love song, he's not someone you want to spend listening time with. The young heroine is played by Shani Wallis, a couple of years before she found cinema fame as Nancy in "Oliver!" She knocks herself out here, literally so in a number ("When He Looks At Me") where she seems to be grafting Eliza Doolittle onto Nellie Forbush. Wallis also seems to have a sibilance problem, which is clearly audible on the recording.

There are songs worth hearing, sure, and collectors will want to get to know this score. What's more, Kritzerland—which really goes out of its way to bring us items like this—is well worth our support. But A Time for Singing is a score which I have never quite been able to embrace.

|

||

| Cover art |

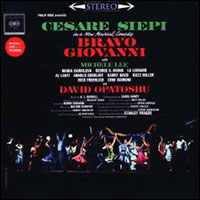

This was a somewhat flimsy musical comedy, built around opera singer Cesare Siepi who played a noble Roman restaurateur fighting against a large-scale eating emporium (with "homogenized tortoni," in twenty-nine flavors) run by an over-the-top George S. Irving. The whole thing is awash in pasta and vino, with good conquering bombast and the middle-aged hero getting the much-younger girl. All the while, Irving's real-life wife—Maria Karnilova, midway between creating Tessie Tura (in Robbins' Gypsy) and Golde (in Robbins' Fiddler)—dances away the night to the Black Bottom and "The Kangaroo." Yes, "The Kangaroo"—and it's wild.

Giovanni was not an earth-shaking enterprise, and it struggled to survive. Phil Rose, the ever-hopeful producer, closed the show in July after a two-month run, but—refusing to say die—quixotically reopened in September. And then shuttered again after a mere week, with who knows how much additional money down the drain.

But the cast recording of the score, by composer Hal Shafer and lyricist Ronny Graham, is full of small delights. Neither dignified nor artful, but delights just the same: "Rome," Siepi's opening number. "I'm All I've Got" and "Steady Steady," for the nineteen-year-old leading lady, a sizzling Michele Lee. Karnilova's dance sequence (including that "Kangaroo"). Siepi's two booming romantic ballads, "If I Were the Man" and "Miranda." There's even an evocative Italian-language theme song, "Ah Camminare," sung by street singer Gene Varrone.

Not the stuff of a classic, mind you; Giovanni is not the sort of prize we'll find over at Encores. But this is a flavorful score, with flavorful orchestrations by Red Ginzler (with Luther Henderson contributing the dance numbers). A Time for Singing had higher aspirations, certainly, and was presumably a better-crafted show; but the Giovanni cast album is pure fun, and I've surely listened to it ten times as much over the years.

|

||

| Cover art |

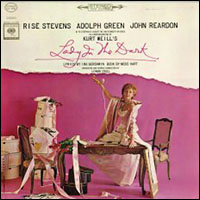

Risë Stevens, the Met mezzo-soprano who died last month at the age of 99, does a wonderful job in the role originally devised by Gertrude Lawrence. (There are existing recordings of Lawrence singing her numbers, but they don't begin to compare to what we get on the Columbia recording.) Adolph Green is a delight as photographer Russell Paxton, the role originally played by Danny Kaye, and John Reardon is on hand as heart-throb Randy Curtis (singing "This Is New").

Lady in the Dark, now making its digital debut, is one of those indispensible Broadway cast albums which you really ought to know if you're interested in serious musical theatre.

(Steven Suskin is author of "Show Tunes" as well as "The Sound of Broadway Music: A Book of Orchestrators and Orchestrations," "Second Act Trouble," the "Broadway Yearbook" series and the "Opening Night on Broadway” books." He can be reached at [email protected])