Great Caesar's ghost has a particularly lively second life in the Julius Caesar that director Phyllida Lloyd has brought from London's Donmar Warehouse to Brooklyn's St. Ann's Warehouse (where it will play through Nov. 9). He's present and accounted for every time one of his assassins gets his comeuppance. Otherwise — and ordinarily — Julius Caesar is a supporting player in the story of his own death.

Possibly you think the play belongs to Caesar's loyal young friend, Mark Antony, since he's the one who has the best lines and is the play's major game-changer.

That particular notion is seconded by the fact that M-G-M's all-star 1953 film rendering — generally regarded as the best and most faithful movie version of the play — had a top-billed, mumble-free Marlon Brando enunciating the role of Antony.

He spent weeks perfecting the character's speeches, listening to and studying every known recording of the part. Finally, he phoned his director, Joseph L. Mankiewicz, to give a listen to the fruits of his diligent labors. When he finished, he asked Mankiewicz what he thought, and the disappointed director said, "I thought you sounded like June Allyson."

Decades later, on the "Today" show, Laurence Olivier said that he could detect some of his own voice and phrasing in Brando's delivery. When it comes to demonstrating whose play it really is, there is nothing like a dame: Dame Harriet Walter, leading an all-female cast of 14, builds a strong, obvious and but-of-course case for Brutus. The true tragedy of Julius Caesar is his — a "noble" and "honorable" man, who gets corrupted by the perverse course of the body politic.

"Brutus is indecisive, but, when he does make decisions, Shakespeare seems to be saying, 'No, that's the wrong decision' — for the right reason," noted Walter. In his indecision and in his ambition, she can see he's part of the Bard brotherhood. "He feels related to Hamlet. He feels related to Macbeth. He has the most fantastic things to say, and he's very complex, so — although he was difficult to get hold of because he keeps contradicting himself all the time — I really quite relish playing him now."

This production came into being to celebrate the first time a pair of women assumed control of a major London theatre. Artistic director Josie Rourke and executive director Kate Pakenham asked Lloyd to create a little something for their inaugural season at the Donmar. "This led to the decision to do an all-female Shakespeare," said Lloyd, "but it was quite a while before I actually committed to Julius Caesar.

"I'd previously directed an all-female comedy at The Globe so I could see how the comedies were easily released into a very playful play by actually having either gender doing it — all-female or all-male — but I wanted to choose something that gave most women a chance to enter a play that they would never have entered. The idea you'd have women on stage calling out words like 'freedom,' 'liberty,' 'tyranny is dead' — they were actually in completely unknown territory. An audience would never have heard these words from the mouths of women in our classical theatre so I wanted to take as many of them as I could out of the romantic and the domestic."

She certainly did that, transplanting Caesar in a high-security women's prison where the inmates, flaunting so much testosterone they should be hosed down, vigorously and violently act out Shakespeare's saga of autonomy and rebellion — something they understood too well, because they are living it. Dressed drably in two shades of gray (charcoal and regulation gray), they go through the emotions of this congested power play until Reality intrudes. At various points, prison "screws" stop the play in its tracks, haul a rotten actor off to solitary and send in the understudy.

|

||

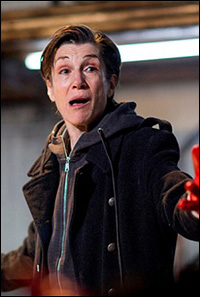

| Walter as Brutus |

||

| Photo by Helen Maybanks |

All warehouses, whether here or abroad, evidently look the same — in their bleak blandness, like The Big House — with metal walkways and stairs for yard exercises, and garage doors that noisily roll open and shut for startling, backlit entrances.

"With St. Ann's, we have those upstage entrances we didn't have in London," remarked Lloyd. "The difference was that, in London, you felt you were stuck in a room with some dangerous women. The audience, I think, felt quite intimidated by being in quite a small space with those women. In Brooklyn, I think you feel more that the women are stuck in a kind of pit. There's a sort of gladiatorial feel about it."

Bounding about that jungle-gym type of set at high rates of speed would seem to invite hazard pay. "There is a certain amount of risk if you're running fast downstairs or sliding down a pole," conceded Walter, "and, with 14 people in a small space, there's a chance you might crash into one another at any given point. It's miraculous what few problems we've had. A lot of our rehearsal period was taken up with how to depict the crowd, how to keep the level of energy very urgent. We worked a lot with a movement director [Ann Yee] and a fight director [Kate Waters], but, of course, you can't prevent 100% accidents from happening. In general, women — especially in classical plays — aren't required to be very physically active."

|

||

| Harriet Walter in Mary Stuart. |

||

| Photo by Joan Marcus |

And what would the Elizabeth she played in Mary Stuart make of this sisters-of-the-cellblock version of Julius Caesar? Walter paused a long, thoughtful beat, and said, "I have a feeling she'd be rather outraged. She was very much fighting for her corner in an all-male world, and the choice she made was to use her femininity in a very clever, very political way, so she might think that for women to actually ape men and pretend to be men would be bad because it had cost her so much to play the role she did and to maintain her virginity and her femininity against a lot of odds. She probably would feel that we were taking the easy way out or something."

Most prominently sharing the stage with Walter's Brutus are Frances Barber's Caesar, Jenny Jules' Cassius and Cush Jumbo's Mark Antony. The latter just picked up a 2013 UK Theatre Award for a performance she gave at the Royal Exchange Theatre between her Mark Antonys: the miserably married Nora of A Doll's House.

In one scene, she and Walter pull off a bit of "stage magic," with the help of Lloyd and her deputy directors of movement and fight. When Brutus presents Antony to the roiling mob, they moved in and seem to devour Brutus, and, when they move back, there's Antony prostrate on the floor, saying "Friends, Romans, countrymen."

"Everything grew organically out of our conversations and our improvisations and the logic of the setting," said Walter. "I don't feel that anything is out of place. I think one of the reasons that happens is that it illustrates very physically that Antony is meeting a hostile crowd, and, by the end, they're all on his side — that is the power of rhetoric — the power and mode of rhetoric on a crowd that is pretty simple and thoroughly interested in Caesar's will, what he gives them in his will, the material benefits. Then, in the very next scene Mark Antony says to Octavius, 'Let's see how we can limit the people's legacy.' The crowd has just been swayed, and it's tragic."

|

||

| Phyllida Lloyd |

For Walter, the hardest thing about this production was not letting her performance get lost in the constant chaos and spectacle. "Because we spent so much time on the improvisations around the prison life, getting a real strong belief in ourselves as a community and working on the choreography in the big set pieces, there was limited time for what I call 'two-handers' and to learn the chunks of lines that I have. I think Brutus has the most to say, so I found the time I had to work on my own, getting behind his dilemma, getting behind what he truly thinks of Caesar."

This is a parsimoniously abridged Julius Caesar, constructed so it can be consumed in a single, pain-free sitting. "We shuffled it around and cut bits of it," Walter said. "Mainly, we cut characters who had only one scene and really didn't add much to the play, so their character might be subsumed in another character, or a little line might be lifted out of a scene that was cut altogether and placed in another part of the play. I think lots of people take those liberties with Shakespeare because we like to get things done quicker. Our version is two hours and five minutes, and I admire the audience sitting. It moves fast, and that helps. Again, that's Phyllida's doing."