*

Robert Morse remembers working with Bob Fosse back in 1961 on getting the choreography just right for How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying. Morse tells Playbill.com, "Fosse said, 'Go into the other room and learn the steps, because you need a little help. Go see my assistant.' And his assistant was his wife — Gwen Verdon."

For Morse, who won a Best Actor Tony Award in the musical for his indelible portrayal of J. Pierrepont Finch, the young and intrepid window washer who rises rapidly from the mail room to the upper echelons of the Worldwide Wicket Company, How to Succeed was itself so overwhelmingly successful because "it was a true reflection of its times."

It was a satire on the office life, the personal life, the daily life of its era, Morse says. "It was a sunny, happy, wonderful production. It was right there in your face, and it was hysterical."

The musical used laughter to shine a comic light on the business world of the early 1960s, he says, just as the current hit TV series "Mad Men" uses drama to delineate that same era. (And Morse should know, since he has portrayed Bertram Cooper, the senior partner of the "Mad Men" advertising agency, in the series' first four years.) Morse is reminiscing about the landmark Pulitzer Prize- and Tony Award-winning musical because it is now being revived on Broadway at the Al Hirschfeld Theatre, starring Daniel ("Harry Potter") Radcliffe as Finch and five-time Emmy Award winner John Larroquette as J.B. Biggley, the Ivy League-educated company president, the role played in the original by the 1920s crooner Rudy Vallee.

Also offering their memories of a show that The New York Times said "belongs to the blue chips of modern musicals" are Tony-winning Broadway veteran Donna McKechnie, who made her Broadway debut in the show's chorus, and Merle Debuskey, the legendary press agent who was the musical's press representative.

| |

|

|

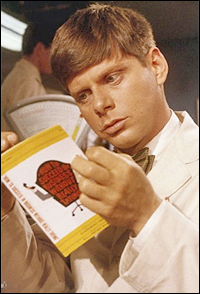

| Robert Morse in the 1967 film adaptation of How to Succeed... | ||

| photo © Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc |

"Everybody came to see it," Morse says. "President John F. Kennedy was there. The show opened with me coming down on a scaffold, wondering if it would break — and this was way before Spider-Man." (The Times described Finch as "a collaboration between Horatio Alger and Machiavelli," a "rumpled, dimpled angel with a streak of Lucifer," and said that Morse essayed the role with "unfaltering bravura and wit.")

Long before everyone came to see it, though, not everyone involved in the production was certain about its chances. But they all wanted success, and they were all really trying.

"I remember that at the first rehearsal, and the second rehearsal, everybody laughed at everything," Morse recalls. "It was all so funny — the idea of me singing 'I Believe in You' into a mirror, the dialogue, the lyrics, everything. Then on the third day of rehearsal nobody laughed. The laughs were over. Everybody got scared. After three or four weeks of rehearsal even the idea of laughter was gone. But Abe Burrows told us that it was sketch comedy. That it goes from one little scene to another. That people in rehearsal have heard it ten times or more, so it's not funny to them. But he said we shouldn't lose faith — it would work. On our first night in our out-of-town tryout in Philadelphia, the house was only half full. But people laughed."

| |

|

|

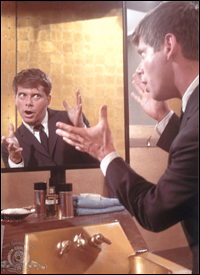

| Robert Morse in the 1967 film adaptation. | ||

| photo © Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc |

Debuskey recalls, "One night, during a dance number, the show's producers, Cy Feuer and Ernie Martin [whose hits included Guys and Dolls, Can-Can, The Boy Friend and Silk Stockings], and Abe Burrows and I were sitting on the steps leading to the mezzanine when Loesser walked in after visiting the box office. He emotionally informed us that the treasurer had told him that an elderly lady had arrived at the box office window and asked, 'When does the Rudy Vallee lecture begin?' That opened an angry window to the accumulated frustration, and everyone tried to come up with a remedy for the lack of business."

The suggested solution, Debuskey says, was to change the title. "Feuer, in his memoir, said that he and Ernie were shaken and agreed to change it. Feuer wrote that 'Debuskey . . . said we were out of our minds. I never saw a guy so angry. He said it was the greatest title he had ever worked on. He threatened to quit if we changed it. Turns out he was right.' "

"Actually," Debuskey says, "I had said, and it was the effective persuader, that the title was an invitation to a Pulitzer Prize."

Among the show's problems in rehearsal was the choreographer: Someone named Hugh Lambert had been hired because Feuer had been impressed with a dance piece Lambert had staged at a trade show. But Lambert wasn't working out — "a problem fortuitously and gloriously remedied," Debuskey says, "by bringing in Bob Fosse to stage the musical numbers."

| |

|

|

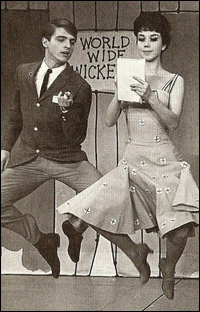

| Donna McKechnie (right), with Tracy Everitt, in the original Broadway production of How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying. |

Fosse and Verdon, his dance captain, hadn't had time to do any preproduction work, McKechnie says, "and they would go home at night and she would tell me later they were doing all their preproduction work at night, jumping up and down on the bed, doing all the combinations and setting the choreography."

McKechnie, who 15 years later would win a Tony as Best Actress in a Musical for A Chorus Line, says she was "a lucky girl" to be chosen for the chorus. She had done summer stock, commercials for grape juice and stockings, and had been in a touring company of West Side Story. "I auditioned for Cy Feuer, for an automobile industrial show that he and Ernie Martin were producing — it was a big show, $2 million, which was big in those days. I got it. And he took me up to the stairs at the back of the Lunt Fontanne Theatre and said, 'We're doing a new show on Broadway and we'd like you to be in it.' And I said, 'Sure.' "

She remembers that during rehearsals Robert Morse "would speak under his breath, and Rudy Vallee was very soft-spoken — he used one of the very first lavalier microphones I remember. At one point Abe Burrows became very frustrated and said, 'Come on, I've got to hear you. It's a comedy!' "

Morse says it was Burrows who got him involved in How to Succeed. "My first Broadway show was in 1955, playing Barnaby in The Matchmaker, opposite Ruth Gordon. After that came the movie version, with Shirley MacLaine and Tony Perkins. Then I went back to New York, where Abe Burrows was putting together a show called Say, Darling, where I played the wonderful part of Ted Snow, who was based on the producer Hal Prince [and for which Morse received a Tony nomination]. After I left that show I was going into a musical called Take Me Along, based on Eugene O'Neill's Ah, Wilderness!, starring Jackie Gleason and Walter Pidgeon, and Abe called me and said, 'I can't stand you working for someone else. We have a show for you that we're developing. After you finish Take Me Along we'll talk about it.' And it was How to Succeed."

| |

|

|

| Composer-lyricist Frank Loesser |

Morse says that he also enjoyed working with Vallee, but that when he first found out that he was going to share the stage with the crooner, he didn't know who his co-star was. "I told my mother and father, and they gasped when I told them I didn't know him," Morse says. "They said the whole country used to turn on their radios and listen to him. I didn't know that in his day he was bigger than even Lady Gaga is today."

Indeed, Debuskey says, Morse was not the only one who hadn't heard of that star of decades earlier — who was often known as "The Vagabond Lover," after the title of his first film, from 1929. Although Vallee had certainly been a household name, and his radio show from the late 1920s through the 1940s had been heard by many millions, when Feuer and Martin went to see him, the crooner was performing in a dismal club in London, Ontario. "The producers flew to Toronto and hired a Piper Cub to transport them over the wilderness to London," Debuskey recalls, "and found him working in a second-rate club, the Silver Slipper, before a sparse audience who did not know nor care who he was. But as soon as he walked out onstage, Feuer and Martin knew they had struck gold; they saw in him the personification of J. B. Biggley."

Vallee was "a very rich man," Debuskey says, "and why he persisted in playing these embarrassing club dates no one other than Vallee could understand."

| |

|

|

| Rudy Vallee and Robert Morse in the 1967 film adaptation. | ||

| photo © Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc |

Nonetheless, Debuskey says, during the often sold-out run of How to Succeed, Vallee exploited his reputation for "real-life parsimony, just as Jack Benny made a trademark out of his character's cheapness. Vallee had a regular order with the box-office for ten standing-room tickets. He could not resell them for a penny more than the actual price, but he sold them only if the buyer would also rent a chair — a cane with a folding seat — that he provided."

That is, Morse says, "until the New York City Fire Department came in and said, 'You can't do that!' "