*

Little did novelist Christopher Isherwood know when he published his 1939 novella "Goodbye to Berlin" — a semi-autobiographical account of his own time in Berlin in the 1930s — what an afterlife the book would have.

Well, not the book itself, exactly, though "Goodbye to Berlin" remains in print and is certainly still read. But the characters he created, including the English #cabaret singer Sally Bowles (the surname was borrowed from novelist Paul Bowles), have had a much more vibrant and public life on stage than they have on the page.

The novel was first adapted for the stage by British playwright John Van Druten. He called it I Am a Camera and focused on the character of Sally, just one of many figures in Isherwood's stories. The title is taken from the opening line of the novel, which runs, "I am a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking." When it bowed on Broadway, it was one of Van Druten's biggest successes and helped make its Sally Bowles, Julie Harris, a star.

Isherwood himself was impressed by the actress. "Miss Harris was more essentially Sally Bowles than the Sally of my book," he said, "and much more like Sally than the real girl who long ago gave me the idea for my character." Four years later it was made into a film, again starring Harris, which was not a success. That might have been stage triumph enough for any literary work. But 15 years after I Am a Camera debuted, director-producer Harold Prince saw something more in the story. He acquired the rights to both the Van Druten and Isherwood material, and drafted librettist Joe Masteroff (with whom he had worked on She Loves Me, and who had worked with Harris on his own play The Warm Peninsula) and the relatively unknown composers John Kander and Fred Ebb to create a musical around the story.

Prince, Kander recalled, was very much in charge of the show's vision. "Hal invented this piece, you have to understand, and we were thrilled to be asked to be a part of it," Kander told Playbill.com. "The show was developed in Hal's living room. We met over and over and over, talking about what if this happened, what if that happened. Out of all of that talking, music came, narrative came. It all seemed to grow on the same tree. Hal had a lot of physical vision of how he wanted the show to look like. Those meetings were very rich. He had certain things he wanted to do that he told us about."

Kander, Ebb and Prince were certain they had hatched a golden idea for a musical. Others, however, were not so sure. "A lot of people said to us afterwards, 'What on earth are you doing?'," remembered Kander. "But it seemed obvious to us that it was a great idea."

| |

|

|

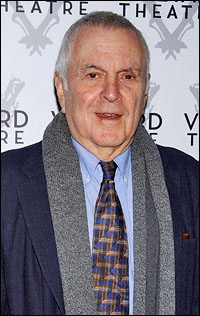

| John Kander | ||

| Photo by Joseph Marzullo/WENN |

"[The show] has so many things against it," Masteroff continued. "In those days, homosexuality could not be discussed on stage in any way. And then there's a girl who doesn't lead a very noble life and has an abortion. And a story that doesn't end happily for everyone in the cast. It's not the sort of thing that Broadway musicals were made of back in 1966."

The trio devised a structure in which the songs were divided between traditionally delivered musical comedy numbers and presentational songs that were offered in the cabaret of the title, the Kit Kat Klub in Berlin. The latter often slyly commented on the the toxic political culture surrounding the characters.

The composer and the librettist worked separately, feeding each other material when they had finished a song or a scene. "We didn't work in the same room," said Masteroff. "Composers and lyricists have their own world. We bookwriters just sit home alone and send our work out into the world."

The first song off Kander's piano was Cabaret's famous opener, "Wilkommen." "Fred and I, throughout most of our career, wrote the first thing first," explained Kander. "In the music — even so simple-minded as that opening vamp is — in the music at the beginning of any show there's an element which informs what the rest of the show's going to be." According to Masteroff, one of the things that changed about the show was the title. "It was originally called Welcome to Berlin," he said, "and many of the women's theatre groups, which were usually most Jewish, said they could never get their groups to go to a show called Welcome to Berlin. So we came up with the name Cabaret."

Prince surrounded the musical with a more dark-hued production that Broadway audiences were then accustomed. (This was the era of Hello, Dolly!) A large mirror, instead of a curtain, faced the audience when they entered the theatre. Joel Grey, as the macabre sybaritic Master of Ceremonies, was androgynous and made up in ghoulish white makeup. The cast also included Jill Haworth as Sally; Bert Convy as Cliff, an American writer who teaches English and has an affair with Sally; the Brecht veteran Lotte Lenya as Fräulein Schneider; Jack Gilford as Herr Schultz, Schneider's Jewish beau; Edward Winter as the Nazi Ernst; and Peg Murray as the prostitute Fraulein Kost.

| |

|

|

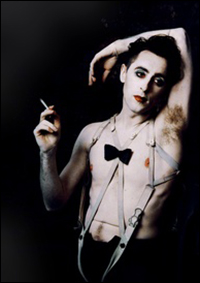

| Alan Cumming as The Emcee |

London saw a West End revival in 1986 with Kelly Hunter at Sally, and the year after Broadway took it up again, with Prince again directing and Grey repeating his role as the Emcee. Prince made the character of Cliff bisexual in that rendition, as had originally been the intention in 1966. The production ran less than a year.

It wasn't until 1993 that Cabaret received a real jump start in reputation when rising director Sam Mendes directed a stark new production at the Donmar Warehouse. Mendes' vision was darker still than Prince's had been, and Alan Cumming's Emcee more openly decadent and sexualized. All the instruments in the orchestra were played by members of the on-stage cabaret boys and girls. "I Don't Care Much," which was cut from the original production, was reinstated, and "Money," "Mein Herr" and "Maybe This Time," now familiar tunes to the public who had seen the film adaptation, were added to the score.

Perhaps most dramatically different was the ending, during which the Emcee stripped off his outer clothes to reveal underneath the striped outfit of a concentration camp prisoner. Other characters did the same, all bearing symbols like yellow badges and pink triangles that identified them as members of groups of people that were demonized and victimized by the Nazis.

The show was such a critical and popular smash that it was brought to Broadway, under the dual direction of Mendes and Rob Marshall. Masteroff brought the staging to the attention of Todd Haimes, the artistic director of the Roundabout Theatre. "I knew Todd Haimes very well because he had produced She Loves Me," said Masteroff, "and I told him he ought to do this terrific show, and he agreed." Cumming repeated his performance; joining him were Natasha Richardson as Sally, John Benjamin Hickey as Cliff, Ron Rifkin as Herr Schultz, Michele Pawk at Fraulein Kost and Mary Louise Wilson as Fraulein Schneider.

The Roundabout Theatre Company transformed the defunct former Broadway house, Henry Miller's Theatre, into the Kit Kat Klub, to house the show. Reviews were excellent and Cabaret became a sellout smash. The show's life was almost cut short, however, when an accident during the construction of the nearby Millennium Hotel caused damage to the theatre. The Roundabout quickly moved the production to another unlikely location: the former home of Studio 54, the legendary disco-age club on W. 54th Street.

There it stayed for the rest of its 2,377-performance run. And there it again plays today.