*

Actors lie about their height.

Director Thomas Kail, whose credits include In the Heights and Lombardi, says résumés for taller actors routinely carve off inches so they'll appear to fit better with shorter colleagues.

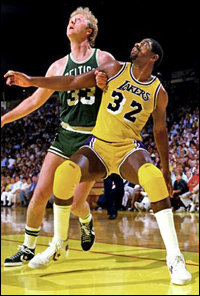

But for Eric Simonson's Magic/Bird, where the two leads are based on real people — real 6-feet-8-inch and 6-feet-9-inch people — the casting call included the unusual phrase "Taller is better."

Kail and producers Fran Kirmser and Tony Ponturo, the team behind Lombardi, tried keeping an open mind as they scoured submission tapes and auditions for actors to portray basketballers Earvin "Magic" Johnson and Larry Bird. "We weren't sure how many great actors were out there that were that height," Kirmser says, so they began thinking that if they found the right people they could scale the other actors and the set to match.

|

||

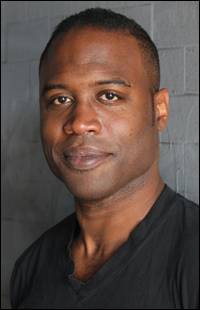

| Kevin Daniels |

This wasn't simply about finding NBA-sized leading men, however. It was about capturing the titular characters' personalities — Johnson's movie-star magnetism and politician-like understanding of people, Bird's quiet intensity and dry wit, which often masked his deep intelligence.

Playing real people "can make some actors apprehensive," Ponturo says. Casting Lombardi, for example, was challenging because the late Packers coach Vince Lombardi has become a mythic figure. And Johnson and Bird are not only icons, they're very much alive. "They will be sitting in the theatre opening night," says Ponturo.

"It definitely made the casting trickier," Kirmser says, though the players' omnipresence in American pop culture for the last 30 years also meant that "the folks walking into the audition room knew more about them, and we got some really informed work."

Still, being prepared is not the same as "capturing the essence" of these people, Ponturo says. For him, facial similarities mattered less than delivering the athletes' "spirit and personality."

"At first you think there'll be a million people, and then you say, 'Wait, there's nobody,'" Cantler says. "And then you find the right person."

|

||

| Larry Bird and Magic Johnson |

||

| NBA |

"I watched the great HBO documentary ["Magic & Bird: A Courtship of Rivals"] a few times to get their relationship and also Larry's Midwestern-country twang," says Coker (who grew up a Celtics fan).

Kail credits Coker for finding a "spareness and coiledness" that captures Bird's intensity, while Cantler adds that Coker was one of the few actors to find Bird's humor. Coker was initially surprised when Kirmser and Ponturo laughed during his callback, but now realizes he shares a "dry sensibility" with Bird. "He's like the kid in the back of the classroom who throws just a couple of barbs, but he talks so little that when he does, it means more."

Magic Johnson is the antithesis. The role needed someone who could light up a room with his smile, explains Ponturo, but not exaggerate the charm into caricature.

That someone was Kevin Daniels. Like Coker, Daniels, 35, is making his Broadway debut, though he understudied for Lincoln Center's Twelfth Night and has done theatre in New York and Los Angeles. Daniels was in New York for a bachelor party a year ago when a friend mentioned the Magic Johnson role. Daniels forgot about it until months later, when his agent called. He says he watched Johnson interviews to "get his very specific vocal pattern in my ear," then made an audition tape with his roommate reading opposite him. He got called to New York, where he found his friend working as the reader in the auditions. The first scene in Daniels' audition involved Johnson being interviewed by a reporter who suddenly injects race into the conversation. "Magic coyly changes the subject, using his charm to make it about her," Daniels says, but he didn't nail it until Kail gave him "the most incisive notes" about how Johnson is affable but also sharp like a politician. Kail was impressed by how Daniels adjusted.

Afterwards, Daniels was called back in to re-do a monologue about how Johnson's father instilled in him his work ethic. When Daniels felt flat, he asked if he could have another go. "You've worked hard and prepared yourself, you should stop and ask to do it again," Kail says, though he adds that he doesn't always say yes.

On his last try, Daniels felt he connected: "They looked as if they'd been in a desert and I was an oasis."

The next day Daniels was back on a film set when his agent and manager called to tell him he got the part. It was Dec. 9, Daniels' birthday.

The cast had its first workshop reading in January. Both men left with plans to immerse themselves in character research before rehearsals. Even though it remained unclear how much — if any — actual basketball would be played on the stage, before the stars departed, Kail offered one parting tip: "If I call you between now and when rehearsals start and you're not on the side of a court, something's wrong," he said, though later he worried they'd get hurt in pickup games. "Maybe I should have told them to just run weave drills."

Not to fret: Daniels planned to work mostly on his ball-handling, while Coker, who used to play in leagues several times a week when he lived in New York, said he aimed to follow Bird's schedule of shooting hundreds of shots a day, including 100 free throws. "I want to see how good I can get before the show starts," he said.