*

Being young and/or broke in New York is no picnic. Whether you're still in school, just starting out, or simply trying to manage a budget with limited means, it can be tough to make the choice between eating three square meals and working down that checklist of Broadway shows still to be seen. Many of us know this dilemma first hand; still others of us have walked past a midtown theatre with a line of rush hopefuls down the block — or, as pedestrians, had to swerve out into the street to avoid a massive crowd of lottery ticket-seekers. From my own rush and lottery experiences — and those of a group of avid rush- and lottery-goers I had a chance to survey — I hope to provide a guide to making your rush or lotto experience go as smoothly as possible.

For those unaware of the same-day ticket phenomenon, a brief explanation is in order. As a means of providing day-of tickets to theatregoers, many (but not all) Broadway shows choose to offer rush tickets — either for students, or for anyone, depending on the show — or hold lottery drawings for a limited number of seats. Sometimes, the seats are located in prime spots in the first two rows; other times the tickets are in less ideal or even partial view spots that the box office might otherwise have a tough time selling.

No matter the location, the tickets play an essential role in many budget-conscious theatregoers' routines — and can provide a word-of-mouth boon to shows by igniting a show's fan base, especially in the current age of social media. Though some complain of higher rush and lottery ticket prices, which have gradually risen over the years (some are now as high as $47), George Strus expresses nothing but gratitude. "It's hard to complain," he said, "when the person sitting three rows in front of you paid $70 more."

The now-established trend of rushes and lotteries on Broadway began with Rent in 1996, which inspired such a craze amongst young theatregoers that fans, who dubbed themselves "Rentheads" would begin lining up, sometimes starting the night before a performance, for the show's $20 rush tickets (eventually the show switched to a lottery to discourage fans from sleeping in front of the theatre). Some, like Rentheads often did, rush the same show over and over again. Another frequent rusher has seen the current revival of Pippin, which he describes as his "downfall," over 50 times thanks to its rush policy. "It's never the same show twice," he said, and he's willing to endure a long wait to see the show on a budget. He's waited as long as 12 hours to attend the show's last performance with its original cast — and for Tony winner Andrea Martin's final performance. Most, though, take advantage of these inexpensive ticket options to see as many of the current Broadway offerings as possible, or use their rush and lotto wiles to impress friends and family from out of town who would otherwise struggle to find inexpensive tickets.

On the less positive side of the spectrum, there are line faux pas that frequent rushers often have to learn to live with, the most prominent being notoriously pesky line-cutters — or those who hold places in line for friends who arrive hours into the rush experience. The unwritten laws of rush prohibit line-cutting and saving spots. If you notice that someone else is violating the "rules," a gentle reminder to a fellow rushers is sometimes all it takes. You can report line-cutters or spot-savers to box office personnel if they're around, but it's not a surefire bet. While some shows keep a close eye on student rushes, oftentimes lines begin forming hours before theatre employees have even arrived on the scene. In the end, some rushers inevitably take advantage of the system.

If you're waiting in line for rush, it's a good idea to know how many tickets can be purchased per person (usually it's two, but not always) and to have an idea of how many you'll be purchasing. Sometimes rushers will take an informal poll of how many rush tickets are "claimed" as a way of gauging whether or not to stick it out. Providing an accurate count for yourself is a good way to respect your fellow line-sitters. If you're one of those counting the line, though (and it's not a bad idea), keep in mind that some people change their minds, so it's not always an exact science.

Those who choose to brave out rush lines or lotteries in person have their superstitions. Claudia Stuart, when she entered the lotto for Hair, would fold her entry slips as fancifully as possible, "into paper hats, origami cranes, anything that would stand out. It usually worked." She warns, though, that many lotteries have now implemented rules regarding how to fold your entry.

Dawn Purvis has another suggestion for lottery-goers — root on your fellow entrants. "I just believe in good karma; cheer on the winners!" Melissa Cox seconds that notion. "Be nice," she says. "You never know who might be standing next to you."

Perhaps the best piece of advice is to plan your day ahead. Playbill.com has a great page outlining each show's rush policies (the individual pages for shows also provide a good source for a show's performance scheduled).

At lotteries offering two ticket per person, Molly Bagby likes to team up with fellow lottery-goers to increase her chances. "If you're one person," she says, "and you find another single, it always doubles your chances." Molly also recommends "staggering when a group puts their names in, and putting a name in at the very last second," though it's hard to say for certain if this makes much of a difference. Also make sure to have cash if necessary (only a few rushes/lotteries allow you to pay by credit card); stated rush policies will usually specify. Check the weather, and also, check the show's schedule before you head out. I once waited an hour or two for rush to see Bette Midler in I'll Eat You Last only to realize there was no performance that day.

| |

|

|

| Neil Patrick Harris | ||

| Photo by Joan Marcus |

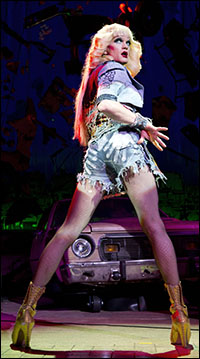

Many shows have now staggered their lottery entry times, giving hopefuls a chance to scurry from one drawing to the next in time for a second shot at glory. Currently, lottery losers for Neil Patrick Harris's run in Hedwig and the Angry Inch, tickets for which are drawn two-and-a-half hours before, can usually scurry across Times Square in time for the If/Then lottery drawing two hours before that show.

Aside from trying other lottos, the concept of "lotto loser seats" has cropped up as a relatively new phenomenon. You'll often hear shows' lottery-pickers shout out "Stick around," after the last name is called, if the show has other remaining tickets to sell, usually for a price slightly higher than that for lottery tickets.

Sometimes shows, whether or not they offer rush or hold a lottery, will also offer same-day standing room only tickets when a performance is sold out (and usually they're strict about this), providing a spot for a ticket-buyer to watch the show from the back of the orchestra (or, less often, the back of the mezzanine or balcony).

Several of those I surveyed recommended the cookie shop Schmackary's on 45th Street as a means of coping with the sting of failure. When Nic Dris loses a lottery, he said, "I go to Schmackary's and eat my feelings." For those who choose to rush or lotto shows, it can add to the overall thrill of the Broadway experience. Dave Osmundsen was once handed $40 cash in a theatre lobby to afford a rush ticket by an extra-generous ticket-buyer. After I've inquired about rush tickets at the box office, from time to time I've had ticketholders approach to ask if I'm in need of a ticket and, by a stroke of miraculous luck, been handed a prime seat free of charge. Rush and especially lotteries can prove unpredictable, or at times feel insurmountably difficult to win, but it's partly the thrill of the chance — and the love of Broadway — that keeps the most die-hard theatre fans returning for that next early-morning wait.

Matthew-Murphy.jpg)