*

Playwright Lorraine Hansberry never won the Pulitzer Prize for her signature work, A Raisin in the Sun. But playwright Bruce Norris sort of won her the award by proxy.

In 2011 Norris collected the prize for his drama Clybourne Park, which borrows from Raisin a character and an uncomfortable social situation. The character — the most risible of those in the Hansberry drama, and the only white one — is Karl Lindner, a weasely figure who visits the African-American Younger household to convince them not to go through with their plans to move to the all-white neighborhood that he represents — Clybourne Park. In Norris' play, set in the house the Youngers have bought, we see how the white couple who sold it to them are petitioned by their neighbors to renege on the deal. The second act, set in 2009, upends the scenario. Clybourne Park is now all-black, and a white couple's plan to buy the same home raises the specter of gentrification and the social upheaval it frequently engenders.

Growing up in Texas, Norris may have been the only budding actor in America ever to dream of playing Karl Lindner. "It was because he was the white guy in the play," says Norris, who had a respectable name as a stage actor before making an even bigger splash as a writer. "And of course I'm living in an all-white neighborhood. Even at that age, I had minimal aspirations to being an actor. So I thought, 'Well, I could play that part.' I had the weird response of knowing the only person I could play was the antagonist."

|

||

| Crystal A. Dickinson and Damon Gupton in Clybourne Park. |

||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

"When we did the play first at Playwrights, I was surprised it did well," says Norris. "When it did well at the Royal Court in London, I was dumbstruck. When it moved to the West End and it did well there, I thought, 'This is just preposterous.' Then the Pulitzer thing happened. Now I just throw up my hands."

Norris' reputation — as a writer and as a person — is as a bluntly spoken contrarian. Despite his background as a performer, being liked is not something he looks for or expects. "It actually feels strange, very strange to me," he says. "I've always judged the worth of the work I do based on how many people hate it. When people approve of something I do, it's deeply confusing for me. I have that adolescent need to piss people off."

Read about the original 1959 Broadway production of A Raisin in the Sun in the Playbill Vault.

|

||

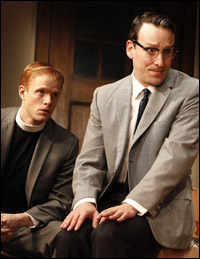

| Christina Kirk and Frank Wood in Clybourne Park. |

||

| Photo by Joan Marcus |

Though he calls acting "the thing I wanted to do my entire life," Norris seems content to neglect his old trade. "I kind of feel I got my fill of doing that, and also reached the limits of what I can convey as an actor." Neither does he necessarily hold the acting game up as a terribly high calling. He once called it a "lazy person's job," and stands by that characterization.

"Being in a play, once you get out of rehearsal into the run of the play, you work two hours a day," he says. "It's not such a hard job." (Before the actors out there howl in indignation, know that Norris thinks that "writing is even lazier.") What isn't a lazy person's job, he says, "is acting in a television series that shoots for..." He pauses briefly before thinking better of following this line of thought. "I don't want to get into that whole thing that has recently happened to me."

|

||

| Brendan Griffin and Jeremy Shamos in Clybourne Park. |

||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

Obviously, the production was eventually salvaged by other producers. And the writer is grateful, while remaining, well, Bruce Norris. "When you grow up you imagine things — the Pulitzer Prize, Broadway, the Royal Court — as things that happen in some Valhalla, some exalted realm that you're looking up to. It's incredibly gratifying to finally reach that supposed summit. But then when you get there and you look around and think, 'Oh, it looks the same here as it does everywhere else,' you think, 'Gosh, these are people just like me.'" (A version of this article appears in the May 2012 issue of Playbill.)