*

Sir Alan Ayckbourn is the only bloke to nab a Tony and an Olivier for lifetime achievements. Luckily for all of us, that lifetime and those achievements continue—with plays outnumbering years. At 72, he just helmed — and attended — the U.S. launch of Opus 75, Neighbourhood Watch, which runs until Jan. 1 at Off-Broadway's 59E59 Theaters.

Surprises — yes, he still has them — is the name of No. 76. "It's written and ready to go next year. I'll start rehearsal around Maytime and open in June. Also, I've the germ of an idea for 77, but I won't write it until October. I'm sorta on a rhythm."

The written and the yet-to-be-written Ayckbourns will both world-premiere at the Stephen Joseph Theatre in Scarborough, England, where all but four of his plays have lifted off. He was artistic director there for a good 40 years — until a stroke five years ago prompted a re-evaluation and persuaded him to relinquish his reins to a younger administrator. Now he only returns, new play in hand, to guest-direct. "It is wonderful," he said of his new life, "all of the fun and none of the responsibilities."

Scarborough is the largest holiday resort in Yorkshire, which, he crowed, is "the biggest county in England — Bronte country, lots of moors" — so, since tourists sometimes translate as audiences for the Joseph, it was unsurprising to find him as a name-brand ambassador for a "Welcome to Yorkshire" tourism campaign. Following a recent Sunday matinee performance of Neighbourhood Watch on East 59th Street, Ayckbourn spoke at a Q&A moderated by theatre pundit, blogger and former American Theatre Wing executive director Howard Sherman — a friend of Ayckbourn and Scarborough (he has summered in the area for the past 14 years). We took notes.

*

|

||

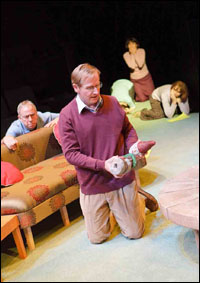

| Matthew Cottle and company in Neighbourhood Watch. |

||

| photo by Karl Andre Photography |

Before writing a word, Ayckbourn sketched out Bluebell Hill, numbered the homes and assigned characters to live in them. "There are more off-stage characters in this play than there are on-stage, but I think it's an old trick that dramatists use quite often," he noted. "Nowadays, you have to — for the economics — but you have to create the feeling of a community by making the rest of them off-stage. And it gives it a third dimension, really. I think some of my most successful characters have never come on, starting with that famous couple in Absurd Person Singular called Dick and Lottie Potter, who are monsters. But you can write monsters off-stage and people in the audience feel, 'Thank God, we're not going to meet them.'"

As it is, a cast of eight constitutes this community — and, actually, that number was dictated by another Ayckbourn play that debuted in rep with Neighbourhood Watch. "I've always been a person who is used to being restricted in terms of what I write. Right from the early days, I knew how many actors I had at my disposal, and I always shaped my plays. Those of you observant enough to notice will see that my earlier plays had between four and six people. And, as one got more successful and went to wealthier places like the National Theatre, there then appeared 12-handers. Those are never — very rarely — done. Most theatres today can't afford to put 12-handers on so, in fact, by doing large-scale plays, you shoot yourself very firmly in the foot. So eight is a big one for me, and Neighbourhood Watch is a response to my earlier adaptation of Uncle Vanya, which I called Dear Uncle [with the same performers] and which I reset in England in the Lake District in 1935."

The London riots last August lent some uninvited topicality to the play, which was, by that point, several weeks deep into rehearsal. "My take is the people stuck in the middle — the reactors to that — so my characters are mostly what happens to a community who thinks of itself as god-fearing and well-behaved — how they react to the notional threat, or sometimes the real threat, of violence against them and their property. This is where people are reacting and saying, 'Well, we'd better protect ourselves,' but it's a devil-and-the-deep-blue-sea situation because what happens if you build a gated community and you can't choose who to lock yourself in with against those outside? Maybe there are more dangerous people living three doors down. The whole thing is slightly allegorical because it accelerates at considerable speed. They put up fences with the speed of light and get on with it."

|

||

| Amanda Root in The Norman Conquests. |

||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

"I emulated her. I thought all mothers sat at the kitchen table and wrote stories, so I started sitting under the table to start with, with my own little typewriter banging away. I wrote terrible, slam-bang action stories. Then I realized a sort of aptitude for dialogue began to develop and a fascination for theatre. I think, from the very earliest of times, I've been a writer. I thought at one stage I wanted to be a journalist with a press tag stuck in my hatband, running around saying, 'Give us the story, ma'am.' Then I realized it really wasn't all that glamorous, so I became a playwright."

|

||

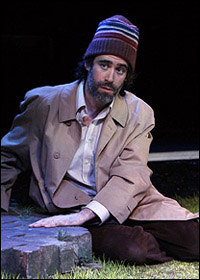

| Stephen Mangan in The Norman Conquests. |

||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

The flip side of this is a London revival of Absurd Person Singular, which opens with a woman obsessively cleaning her kitchen. "I saw the first preview, then I saw it again ten performances later, and it was appalling. In the first performance, she was polishing away, and it was perfectly truthful polishing. By the time I saw it the second time, she's spraying her husband and polishing him as well. That's silly. Stop it! She was trying desperately to get a laugh from something that wasn't even true. It was sad. The play faltered from page five and got less and less credible as it went on. You can see the desperation setting in for a company like that. Where have all the laughs gone? And you want to say, 'Where's the belief gone? Where's the trust gone? We don't believe you. We don't really want to know about you anymore.'

"My plays always just teeter along a razor blade, really, of tragedy and comedy. Hopefully, people are uncertain when quite to laugh. I like it that way, if you can draw the two strands together. The best theatre to me is that tension between laughter and sadness. I stopped calling my plays comedies years ago. They are 'A Play By.' They're neither 'A Drama By' nor 'A Tragedy By' nor 'A Comedy By.' If you say 'A Hilarious Comedy By' and it's not, then they'll sue you if they don't laugh."

|

||

| Claudia Elmhirst and Bill Champion in the New York premiere of Intimate Exchanges. |

||

| photo by Tony Bartholomew |

"Then, he did Private Fears in Public Places, and, in that case, that was so filmic — it's a play in 52 scenes, which is a big play for me. I don't usually work in short-shot scenes. It keeps cross-cutting from one location to another — very filmic. He took that script and never deviated from it. It is exactly the same, shot for shot."

"Except that everyone was prettier in the movie!" Sherman injected, prompting a laugh — and a story — from Ayckborn: "I once complained about a very, very glamorous cast for a play of mine in Paris called How the Other Half Loves. The whole play was based on the fact they're not glamorous. There's a glamorous woman, and then there's a hard-working, driven, socially angry housewife, and then there's a woman with absolutely no taste in clothes, and she looks ghastly. The comedy was based on the fact that they contrast. When I saw the premiere, all these beautiful women and men swan on, and I said to the producer afterward, 'Well, I enjoyed it, but why did you have to make them all so beautiful?' He said, 'In Paris, we do not wish to sit and look at ugly people.' Funny, they seem to love it in England."

|

||

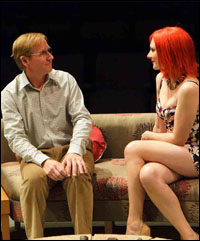

| Matthew Cottle and Frances Grey in Neighbourhood Watch. |

||

| photo by Karl Andre Photography |

"The short answer is 'Probably the next one.' I have a naïve hope that I've just been improving all the time. Probably not, but hopefully the general feeling is upwards. So the blank sheet of paper — just the idea — as soon as you write a word, even if it's only Act One, you've spoiled it. The ones in your head are the ones that have no limits." Moderator Sherman then wrapped it up in a big bow: "Upwards is a note to end on."

(Harry Haun is a longtime staff writer for Playbill magazine whose work, including his Playbill On Opening Night columns, is frequently seen on Playbill.com.)