Packed with celebrities, members of the creative and producing teams, alumni from Broadway and U.S. touring casts, and supportive industry folk (plus 200 civilians who were winners of a Phantom contest cooked up by the producers), the Majestic was aglow like never before. Tuxes, glamorous attire, smart suits, and even some wearers of masks were seen throughout the house.

Lights came up on the Harold Prince production at 6:50 PM (20 minutes later than expected), and at the climax of the famous opening auction scene, when the Paris Opera's broken chandelier is illuminated with electric lights, the audience roared its approval.

Up went the chandelier, to its rightful place above the crowd, until it was time for it to plunge toward the stage in what is one of the most famous scenes in musical theatre history. (Maybe as famous as Nellie Forbush washing her hair onstage in South Pacific, which also occurred at the Majestic.)

Applause rolled freely in the first act. In one case, when George Lee Andrews first appeared, as new opera manager Monsieur Andre, the generous applause stopped the show. Andrews, the well-liked actor whose association with director Prince goes back to the original production of A Little Night Music (he was butler Frid), has been with the Broadway production of Phantom since Day One (he was the understudy for Firmin and Andre and played onstage roles, as well, 18 years ago).

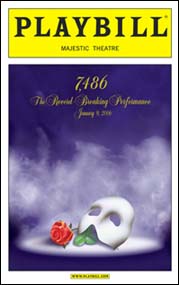

The first day of previews for the Broadway run of Phantom, by weird coincidence, was also Jan. 9, but in 1988. On Jan. 9, 2006, the staging celebrated performance No. 7,486, surpassing producer Cameron Mackintosh and Lloyd Webber's Cats by one performance. The audience was part of history Jan. 9, and knew it.

|

|

|

|

The "Masquerade" tableau — which also featured members of the show's national touring company — at the top of Act Two prompted cheers and applause as well. (Can anyone resist ornate costumes and actors positioned on a sweeping staircase?)

The tension and thrill in the air at the Majestic may have had less to do with the Victorian romance and melodrama on stage than the expectation that something bigger was coming at the end of the evening.

Bigger than pyrotechnics, a candlelit underground lake and a creepy kiss? Much bigger. News had already been released that a special climax had been devised for the end of the milestone performance.

Following the show's regular bows (cue thunderous applause), the company disappeared and the winsome ballerinas gathered in a circle to reveal from their group a solo female dancer in white spandex. Offering several signature stretches from Gillian Lynne's Cats choreography, the dancer inched her way (under a wide, illuminated moon) toward Howard McGillin in his Phantom garb, and took his hand.

With that gesture, a metaphoric torch was passed, from one Lynne-choreographed show to the next, from one Cameron Mackintosh-produced show to the next, from one Lloyd Webber-composed show to the next, from one longest-runner to the next.

McGillin gently bowed to the feline (no, she was not in full makeup and yak fur as the Cats troupers had been for years, between 1982-2000) and she exited nobly into the wings, allowing Phantom its place in history.

Then came a choreographed parade of alumni. A gaggle of Andres and Firmins, a pack of Phantoms, a rush of Raouls, a chorus of Carlottas, a crush of Christines. There was Broadway's first Carlotta, Tony Award winner Judy Kaye; there was a touring Christine, Diane Sutherland (formerly Fratantoni); there was onetime ensemble member Rebecca Luker, who graduated to Christine; there was original Firmin Nick Wyman, a towering presence.

And then the massive company parted to reveal Andrew Lloyd Webber, characteristically not at ease with public exposure but gob-smacked by the import of the evening. He thanked his colleagues (including unseen writers Charles Hart and Richard Stilgoe and former wife, Sarah Brightman, the first Christine, who was not present). Appearances were made by the legendary Prince (who noted the U.S. productions have employed some 6,850 people), choreographer Lynne (who remembered the late Steve Barton, who created Raoul in London and New York) and Mackintosh (who remembered the late production designer Maria Bjornson, whose massive and detailed scenic work is a virtual character in the show). Mackintosh also pointed out that it was 26 years ago this month that he and Lloyd Webber first met and had a long lunch to discuss a partnership that would result first with Cats.

Then the crowd parted again to reveal Michael Crawford, the Tony Award-winning originator of the title role in London and on Broadway. Shaken with emotion, he admitted that this was the first time he had ever seen Phantom from the other side of the footlights. Crawford remarked that it was an equally thrilling experience, thanks to the splendid performances of Howard McGillin, Sandra Joseph and Tim Martin Gleason. He also thanked composer Lloyd Webber for the role that changed his life.

Silver confetti, streamers and black balloons with Phantom masks exploded into the audience, leaving nothing left but to sweep up and prepare for No. 7,487.

And counting.