*

When Jez Butterworth's new three-act, three-hour play Jerusalem opened on Broadway to largely rave reviews in April, New York dramatic critics put their otherwise moth-eaten bachelors degrees in English Literature to work, pumping their reviews with a Norton Anthology's worth of the literary, historical and mythological references that they spied in the English playwright's rich, ambitious tale. One felt that an annotated edition of the play might soon appear at the book store.

There's only one problem with all the citations, allusions, allegories, literary echoes and parables that critics claimed were in Jerusalem — Butterworth says he didn't knowingly intend any of them.

"There was never an attempt in any kind of codified way to make it adhere with any existing allegory," said Butterworth, who talked to Playbill from the small, isolated farm in Somerset where he lives with his family, and breeds and butchers his own pigs. "Nobody wants to be in a situation where you feel you need a kind of crib sheet in a play. There's so much about T.S. Eliot's poem I hate, but I remember being at school and getting to the end of 'The Wasteland' and there being notes, and thinking, 'Oh, God!'"

Butterworth will admit to only a single overarching mythological theme in the play, which is set on St. George's Day, April 23. "I think there's something in there very identifiable about St. George and the Dragon. The Dragon keeps a maiden hidden and someone has to come and free her." Even then, he admitted to being a bit "shaky on the myth." So does that that make Johnny "Rooster" Byron (played by Mark Rylance in a towering performance) the dragon? Byron is the play's central antihero, an iconoclastic, drug-dealing squatter who functions as a sort of larger-than-life woodland father figure to the town's teenagers, and resists the surrounding Wiltshire villagers' attempts to remove him to make way for new housing. He does, after all, hide the town's teenage May queen, of the annual Flintock Fair, in his trailer during the play. And an avenger of a sort does come to rescue her and "slay" him. "I probably never sat down to imagine it as such," was the playwright's reply.

| |

|

|

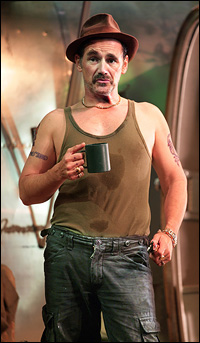

| Mark Rylance as Johnny "Rooster" Byron | ||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

"I think there are so many" possible comparisons, he said. "If you tap into a spirit, a defiant spirit, it's going to chime with other renderings of that. Funny enough, I wasn't really that familiar with Henry IV, Part I & II. I checked it out closely after writing the play. I think there certainly are some similarities. But I think there's a cowardice in Falstaff that you can't identify in Johnny Byron."

As for the character's loaded name, some have thought of it as a reference to Lord Byron, the English poet, and one of the more sybaritic, romantic and dangerous figures in English history. (He also had a clubfoot, which is echoed by Rooster's limp.) But no dice. "There was a guy called Byron in a village in Suffolk in the early '70s when I was very small," tells Butterworth. "He was a very out-of-control, otherworldly character, and he just stuck with me as a name. I kind of resisted calling him that just because of Lord Byron. But in the end I went with it, because once a name sticks, it sticks. And I don't mind the overtones."

Byron was, in fact, based on a number of characters Butterworth has known over the years. Aside from the bloke mentioned above, one was a man he knew in a village in Wiltshire. Once, he charged into him by mistake, and remembers it being "like walking into a tree." A while later, after teaming with him in a victorious pool match, he picked him up "and he was light as a feather. He could change from one thing to another."

This corresponds to Butterworth's view of Byron. "I think what's most interesting is that he keeps changing. He's a very slippery character."

| |

|

|

| An 1824 portrait of Lord Byron by Thomas Phillips |

Butterworth also explained that the town where the play is set, Flintock — and the Flintock Fair, which takes place during the play — are fictional. Flintock is based on the village of Pewsey, where Butterworth lived for a time.

Finally, there's the title. "Jerusalem," which uses as its text a short poem by William Blake called "And did those feet in ancient time," set to music by Sir Hubert Parry in 1916, is one of the most anthemic of English national songs. The poem was inspired by the apocryphal myth that Jesus visited England during his days on Earth. "I always loved the song," explained Butterworth. "It's the type of song that, if you go to a wedding and sing six hymns, it's the one that will stand your hair on end. It's really powerful. It's full of questions, of course. It's full of wonder and unanswered questions, which is exciting. The decision to call it Jerusalem is a kind of a bold move. It's a totemic title. It's takes balls to call it that. It fits it well. I think Blake's song and my play are both celebrations and lamentations at the same time of a lost state."

Ironically, the play that is called Jerusalem and is (arguably) about England, was written in New York City. "I had a draft of it before," said the writer. "I was in New York producing a film in 2009. But It was really written in New York out of necessity. It was already April-May. And we were supposed to start rehearsing in June. I have to kind of work at night, and quite fast. But it came together fairly well. Deadlines can either freeze you up or free you." So can 1,000 years of history. Just ask Rooster.