*

If there's a soul adrift — physically or spiritually — in the Gem State, chances are good he sprang from the fertile pen of Samuel D. Hunter.

Commissioned new plays from the Boise-reared Hunter are popping up in New York and at regional theatres all over the country, particularly on the West Coast where theatregoers saw the world premiere of Hunter's The Few at San Diego's Old Globe Theatre in October 2013. 2014 is fast shaping up to be the year of the Hunter with the world premiere of A Great Wilderness having begun performances at Seattle Repertory Theatre Jan. 17, followed at the end of March by Rest at Costa Mesa's South Coast Repertory — while Hunter's award-winners The Whale and A Bright New Boise are scheduled for a new publishing March 24.

Apart from their Idaho setting, the plays have some thematic threads in common — most notably the intricately drawn characters who could take their proper place in a great cosmic lost and found: Charlie The Whale's 600-pound writing instructor holed up in his apartment trying to reconnect with his estranged daughter; Gerald, the 91-year old Alzheimer's patient who has escaped his shuttering nursing home in Rest; and Walt, who, late in life, is coming to an uncomfortable reckoning about the conversion therapy he has been practicing for so many years out in the woods of A Great Wilderness.

"Synge said plays should be fully flavored like a berry or a nut," said Martin Benson, who directed the West Coast premiere of The Whale at SCR last season and who will direct SCR's Rest. "Everything I've read of Sam's, there's sort of a berry or nut, but the flavors within it are also piquant and interesting. The people are so vivid." And to that previous list of people who adrift, you can add one other person, said Benson. That would be the playwright himself.

"He virtually lives nowhere," Benson said. "I know he and his husband are buying an apartment in New York, but he's been attending the rehearsals of all his plays, so he's been staying in resident housing in San Diego and Seattle."

The playwright himself is a sharp and well-spoken man who trained at NYU, the Iowa Playwrights Workshop and Julliard and now lives in New York but also refers to himself as a Pacific Northwest playwright. Although he has been on the record as stating that elements of his plays are drawn from his own life, Hunter is by no means working out demons or trumpeting social or political agendas.

| |

|

|

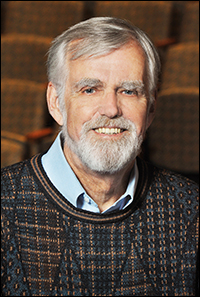

| Martin Benson |

Fundamentalist Christianity, he said, "sort of informs who I am and it informed my world view. I think it just gave me an insight into how one lives with fundamentalist beliefs in America in 2014, which is very interesting way to live right now — holding these sort of literal interpretations of the Bible in the present day. It's a very difficult thing to do and it just creates a lot of interesting tension for these people."

To some extent, A Great Wilderness continues the conversation begun in Hunter's Obie–award winning 2011 play A Bright New Boise. In Boise, Will, a former official in a now-disgraced church has relocated to Boise, where he has taken a job at a craft store called Hobby Lobby. Here Will tries both to connect with the son who he gave up for adoption as an infant and waits for the rapture which — despite the disbanding of his previous congregation — he still very much believes is coming.

A Bright New Boise had a boy named Daniel who lost his life in the wilderness ostensibly while under the protection of men of God. In A Great Wilderness a 16 year-old boy finds Walt. The boy's name is also Daniel.

"The dramatic clothesline of the play is that there's this kid lost out in the forest with the dramatic questions being, 'Where is this kid? Will he come back?'" said Hunter. "That crisis brings out in these other characters some of their most deeply held beliefs and puts them into question." The intricacies and conflicting agendas of religion are other threads that run through Hunter's plays. The playwright grew up attending fundamentalist Christian schools, and, if the ever-questioning and often disgraced characters of his plays are any indication, he is still going to school.

"Ever since I started writing plays in college, I've been writing about religion and especially how fundamentalism and evangelical Christianity functions in a world that is increasingly becoming more modern and racing toward the future," the playwright said. "In A Great Wilderness, it's sort of like a group of people who are clinging to the past. That dynamic, that tension, has always been really interesting to me. It's also something I don't see discussed a lot on our stages, which is curious just because we live in such a religious country."

| |

|

|

| Braden Abraham |

In the wake of Exodus' closing, and the disgrace of its president Alan Chambers acknowledging that he still had same-sex attractions, the states of New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Ohio and Hawaii have introduced or passed legislation banning conversion therapy.

Not only is A Great Wilderness' Walt no Alan Chambers, Walt eschews organizations that practice formalized methods of conversion. He trusts the methods he has been practicing for decades, but is now seeing what a toll his work has taken. He lives in an Idaho cabin and is, according to Hunter, very much his own island.

In creating Walt, Hunter conducted a certain amount of research into conversion therapy. But he and dramaturg/husband John M. Baker did this research after Hunter had written the first draft of A Great Wilderness in order to keep the play from being "entirely about the research."

"The easiest thing in world would be to write a play about gay conversion therapy, and in the end we all learn that it's wrong. The fact that it's wrong has been very much illustrated and is apparent," said Hunter. "The play is more about how this man's obsession has laid waste not only to his own life but to the lives of the people around him. This character stridently believes that he is operating from a place of love and generosity. That's a tragic flaw that leads to the destruction of his entire life." Playing the role of Walt is Michael Winters, who not only did the first reading of A Great Wilderness in August 2012 (when it was titled Exodus), but whose last stage gig was playing another famously aging and deluded character, the title role in Shakespeare's King Lear at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival.

And yes, Winters said the journey through Lear was fruitful preparation for Walt.

"Once I started to realize that both of them are aging and are starting to have mental difficulties, I thought about how that affects their behavior and perceptions," said Winters. "Lear does everything externally. Everything he's thinking and feeling is right out here and he's talking about it and Walt is the opposite. Everything that happens to him happens internally and you sort of have to read the signs and put the pieces together as he is doing over the course of an evening."

"Sam gives his characters such integrity," agreed Braden Abraham, who is directing A Great Wilderness and who has helped shepherd the play through its development. "In order to get to the complete evisceration of this practice, Sam takes us inside these characters to you see their internal struggle. I love this play because it's a real tragedy about the price of living a lie."