*

New York City stages have been filled with puppetry this season, from the evocative shadow puppets used in The Scottsboro Boys to the zany playhouse pals at Pee-wee Herman on Broadway to The Addams Family's creatures of the night. Gotham is also preparing to welcome the life-size equestrian puppets of War Horse, and the Bunraku work of Compulsion, the story of Anne Frank's diary.

It was only natural that Playbill.com should go to renowned puppeteer Basil Twist — whose works include the music-filled spectacle Arias With a Twist, Peter and Wendy, Symphonie Fantastique and Petrushka — for an insider's look at what it takes to pull the strings of puppetry magic.

You're a third-generation puppeteer. Was this something you always knew you'd do? I can't imagine puppeteers forcing their kids to take over the family business.

Basil Twist: I was enchanted by it as a kid. My mother was doing it and I was close enough to appreciate it. I do like performing and the thing about puppetry is, generally, you're not drawing attention to yourself. I was very shy as a child, but I still had a theatrical flair, so to speak, so it was the perfect way for me to perform and still protect myself. To get attention, but not necessarily draw attention to myself. That's actually a very real reason why a lot of puppeteers start to do it. You went on to study at the École Supérieure Nationale des Arts de la Marionnette, France's first and only puppetry school, correct? That's an auspicious beginning for an American artist.

BT: Yes. That experience just pushed me to do bigger and better things. I try to make good on the incredible opportunities I had. When I first came to New York I met Julie Taymor early on and worked on Juan Darien. That was an amazing experience for me. I've been really blessed. That's part of what pushes me to make the coolest stuff I can, because I feel like I lucked out. I've had these amazing opportunities and I owe it to the universe because the universe gave these great gifts and opportunities to me.

Your work is well known internationally and you're sort of this downtown darling of New York's theatre scene. Had Broadway been something you wanted to tackle?

| |

|

|

| Julian Crouch | ||

| photo by Joseph Marzullo/WENN |

You're also involved with The Pee-Wee Herman Show on Broadway.

BT: I came to know Pee-wee from Arias With a Twist. Paul Reubens was an original member of the Groundlings [where Pee-wee was born] with Joey Arias [the acclaimed drag artist who starred in Arias With a Twist]. He came to see Arias and was enchanted with my work. He wanted me to do all the puppetry for the show in L.A., but I couldn't because I was doing The Addams Family. But I served as a creative consultant and when the show did finally make it to New York, I had more room in my schedule and I said, "Of course."

Did you start from scratch and rebuild all of the puppets for Pee-wee on Broadway?

BT: No. It was an unusual process for me. The puppets were built by several different puppet builders in L.A., mostly in the television industry. There were specifics that I suggested, of course, building things for television are totally different than doing it on stage. I have huge respect for the people who built them in L.A.

When the show finally came to Broadway there were some key sequences that Paul wanted to completely overhaul or augment. Obviously, those are iconic characters that were all developed years and years ago, so there's not a lot of wiggle room for me to put my full interpretation on them.

I worked with director Alex Timbers and Paul to get the puppetry to a higher level. There has to be clarity of gesture. No puppet can do everything. You have to make them do the things that they are supposed to do well, and then the rest is left to the imagination.

What moments were you specifically keen on?

BT: Pterri the Pterodactyl. He needs to fly well and it's a key part of the story because Pee-wee wants to fly himself. I wasn't quite satisfied with the way that puppet flew and how his wings flapped. String marionettes are very, very difficult, and I almost hesitated to go in there and change stuff. But the puppeteers I work with were also eager to make it be better. So, I worked together with puppeteers who are regular members of my shows and kind of revised how that puppet worked and how his wings flapped.

Those familiar with your aesthetic might be able to pick out signature Basil Twist moments. I couldn't help but see your handiwork all over the flying sequences in The Addams Family and Pee-wee.

BT: Yes. The flying sequence was probably the most important thing to Paul [in Pee-wee] that I helped to make bigger and better. I took the reigns on that. He wanted it to be more poetic and sublime. He wanted to really fly, to make it actually go somewhere more fantastical. It was put in my hands to execute it as beautifully as I could.

|

| Paul Reubens with Pterri the Pterodactyl and company |

| photo by Joan Marcus |

| |

|

|

| Jackie Hoffman and Adam Riegler in The Addams Family | ||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

BT: In The Addams Family, most of those people never had any puppetry experience before, it's the ensemble and the chorus. It was important to cultivate and to draw out of them the willingness to do this new art form. You have to be really selfless in a way that many performers are not used to. You're hidden and you might have to get into uncomfortable positions, and no one may necessarily even know that you are doing it. Those performers were really game to do something really different I'm really proud of them.

One of my favorite moments is the monster under Pugsley's bed. Is there a whole team working under there?

BT: That's actually one person. That's a really cool thing. [It's] Liz Ramos, the dance captain. She is the definition of what I like in a performer who has puppetry on her plate. She is game and she's up for it. She said, "Ok, I'll do it. I'll squish myself under that bed and put this one thing on my foot, this thing on my hand and this other thing on and I'll use my head to work this." She's the perfect example of the kind of performer it takes.

Audiences are also game. Your work on The Addams Family was singled out by the critics. Besides creative design work, what draws people to these creatures? BT: It invites the audience to participate in a different way. People have to meet any puppet on stage half way because they have to bring their imagination to it. There's this phenomenon of suspension of disbelief, where you completely know the puppet is made of wood and you know that there's not really a pterodactyl flying around the stage. Paula Vogel said once, "Suspension of disbelief my ass, it's belief!" You believe, you have to believe in it. That is exciting and challenging and engaging in totally different way than when you do when you melt into your seat at a movie.

It's hand-made, one-of-a-kind art form, in an age of mass-produced, commercial entertainment.

BT: We are so inundated with computers and this online world that there's something very powerful about this low-tech magic that happens between an audience and performers with puppets. The experience reminds us of an ancient part of ourselves that still believes in magic. A computer screen and an iPad are completely magical, but we so don’t care about it. If it's slow to download you just get angry at it, we don’t have an appreciation of that magic.

In a puppet show, it's a very simple form of magic that we understand. It stimulates a primal part of your brain where we see things come alive. It engages an audience in a way that is a primal part of being human, where we see life in something that is not alive. It's a very profound way of relating to something.

| |

|

|

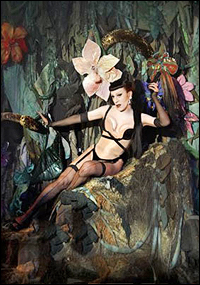

| A scene from Arias With a Twist |

BT: I've been really lucky to work with some great collaborators and to help take their vision farther, but what I've mostly done, is that I create my own shows, my own entire universes. I'm looking forward to the day that I can do that myself on Broadway. It would be great to be the leader on a show, to choose it, to conceive it and direct it.

Are there certain types of puppets or techniques that you find yourself particularly drawn to?

BT: When I make my shows I chose the puppets that I really want and that I love the most. Then I make the set and all the other elements work around that so it serves the puppetry. I love the style of puppeteering with three-man manipulation, it's based on a Japanese technique [Bunraku]. I think it's really expressive and moving and powerful.

How do you begin to design?

BT: I start by thinking, "Where is the puppeteer? Do you want them visible?" It's the degree of how far they are away from the puppet that starts to determine the technique. If you don't mind that you see the puppeteer, like in Avenue Q, then the puppeteer can be right there and it's part of the delight of seeing the puppeteer at work.

On certain projects, you have to look at the set and say, "Here's where we want the puppet, now where does the puppeteer go?" Having someone on a catwalk up above and working the puppet on strings is always a surefire way of getting rid of the puppeteer, but that it's a really hard technique and it doesn't have the same quality of movement. It's important what kind of movement it's going to have. Will it be a strong dynamic movement, or a more ethereal and a little more accidental movement?

But, every puppet is different. Puppets are frequently so different that it's always a new experience. It's a rare situation where you'll find a puppeteer who has had the exact kind of experience you need for a certain kind of puppet.

There are two shows coming this season that incorporate puppetry, including Compulsion at the Public Theater and the London import of War Horse at Lincoln Center. Is it gratifying for you to see audiences and producers embrace puppetry?

BT: I'm excited for War Horse to come to New York. I think it's going to blow people away. The empathy people need to bring with them to participate as an audience in that theatrical experience is going to be overwhelming for people. The puppet is like an antenna that serves as the capturer of energy between the performers and the audience and both parties are putting a lot of energy into that object. It's astounding to see what happens to the audience when they're in the presence of these creations that they need to believe in and they do.

View highlights from The Pee-wee Herman Show and The Addams Family: