In 1974, Paula Vogel—then a first-year graduate student at Cornell University—picked up a yellow, out-of-print English translation of Sholem Asch’s drama God of Vengeance per a professor’s recommendation. She stood in the library as she read through the entire play, setting her on a path that has now led to an overdue Broadway debut and Tony Award nomination.

Indecent is Vogel’s examination of the 1903 conception of the Yiddish playwright’s landmark work, the 1923 obscenity trial it provoked, and the resilient nature of performance it embodied for decades to come. (It won Tony Awards for director Rebecca Taichman and lighting designer Christopher Akerlind.)

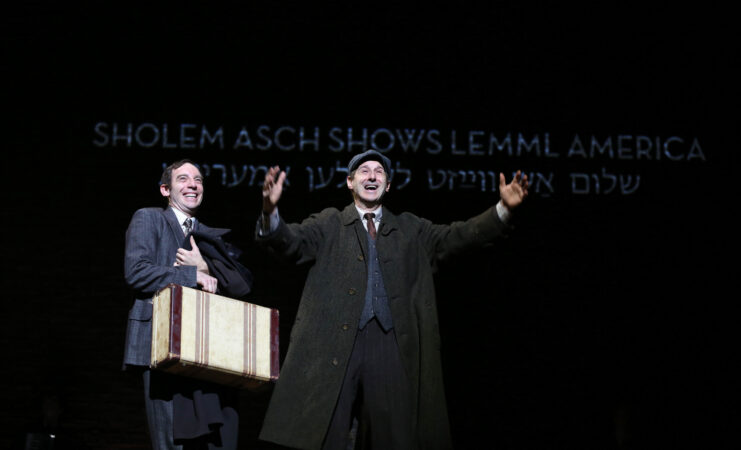

Katrina Lenk and Adina Verson in Indecent

Carol Rosegg“To this day, I’ve never seen a greater love scene written,” Vogel says, referring to God of Vengeance’s Act II scene between two women. “It took my breath away,” the Pulitzer Prize winner adds, echoing one of her own lines in Indecent. “This man was dead, and he was basically saying to me, ‘You’re not alone.’”

Vogel’s piece was seven years in the making and stemmed from a time in American history when Vogel noted that hate speech was on the rise. “I don’t think playwrights can choose their time,” she says. “That’s something Sholem Asch said at the end of his life. Art matters when we’re in political danger; art matters when we’re in the middle of division.”

Indecent arrived on Broadway at the Cort Theatre just weeks after the Trump administration announced its intention to eliminate the National Endowment for the Arts. Vogel knows the fight to protect art from censorship is nothing new; it’s the driving force of the play. “I wanted to look back and see how vital the arts were to a Jewish immigrant population, and to a Jewish population that was almost eradicated.”

Read: PAULA VOGEL IN DEFENSE OF THE NEA: 'YOU ARE NOT MAKING AMERICA GREAT'

Though the new play takes on a timeliness from current political discourse, Vogel insists that Indecent—like all her writing—was born primarily out of her own personal sense of marginalization: marginalization as a gay woman with a Jewish legacy.

“One of the things that concerns me is that we become aware of our marginalization rather than proclaiming it as this proud identity—something that makes us a unique and vital part of America.”

How does a story set in the early-to-mid 20th century shed light on the state of a nation in 2017? “You never write a history play about the actual history. Yes, this obscenity trial happened. But it really has to do with us as Americans now. All history plays are about the present moment. I put together the strands of everything that is dividing us now.”

In the wake of hate speech, marginalization, and censorship, Indecent becomes a battle cry for resistance. But it’s also a love letter to art, proving the two are not mutually exclusive. “The only way we can keep active is to make sure that we laugh,” Vogel says. “Arts keeps the heart resilient. Activism keeps us resistant. They go hand in hand.

“There’s nothing more deadly to our ability to fight back and resist than being deadly serious and solemn.”

(A version of this story was first published June 14, 2017.)