*

Thirty years after it premiered in Central Park at the Delacorte Theater under the wing of the New York Shakespeare Festival (now the Public Theater), Rupert Holmes' Tony-winning musical The Mystery of Edwin Drood is enjoying a vivacious revival by the Roundabout Theatre Company at Studio 54. Drood's rousing and intricate period score has been preserved anew thanks to a lavishly packaged two-disc revival cast album from DRG Records, which was released in late January.

Playbill.com caught up with Holmes to discuss revisiting Drood for this fresh production, his new revisions, and some of the initial inspirations for the musical. We also look back at his career as a singer-songwriter.

Rupert, before we get to Drood, I have to tell you that a friend turned me on to your solo studio albums from the 1970s and 80s. I know that you're best known for "Escape (The Piña Colada Song)," but I am such a huge fan of the songs "Him," "Partners in Crime," "Wide Screen," "Who, What, When, Where Why" and "Answering Machine." That is some great pop writing and storytelling.

Rupert Holmes: Thank you. People think the first record I ever made had the "Pina Colada Song" on it. In today's music industry, I wouldn't have lasted that long. I wouldn't have gotten to make a fifth album. But thankfully, my first album, "Wide Screen," was sort of a critics' darling — everyone raved about it, but no one bought it. They only manufactured 10,000 copies, I wasn't even in the running for failure! But one of those albums found its way to Barbra Streisand, and she suddenly wanted to record my songs, and have me arrange and conduct them. I think that alone caused CBS to renew my contract for several years. The cover versions of my songs that were being recorded are what kept me in the running. But it wasn't until my album "Partners in Crime" that I actually had a couple of top ten hits.

| |

|

|

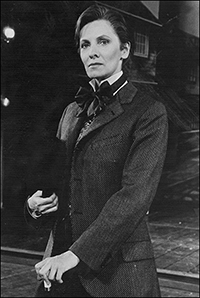

| Betty Buckley in the original Broadway production of The Mystery of Edwin Drood. | ||

| photo by Martha Swope |

It was as if someone finally picked up the message I was trying to send which was, "Please, let me find a way into musical theatre."

Had The Mystery of Edwin Drood been on your mind at that point?

RH: I first had the thought about making a musical of "Edwin Drood" as far back as 1971. I read the novel. I thought it would make a terrific musical because John Jasper is a choir master and organist, and he's madly in love with his muse and pupil, so I knew he would have every reason to write her a song for her birthday that would put into her mouth the word he longed for her to speak to him.

Then there came the thought of, "How do I deal with the fact that it's an unfinished work?" And within a day or two of first considering the show as the subject of a musical, I hit upon the idea that I would not try to do my mock-Dickensian ending. Instead, I would find some way to allow the audience to vote on several of the questions raised in the plot, and have the possibility of a different outcome at every performance. Because, to me, entering the theatre, that would be the absolute height of theatricality, and would do something, especially in those days, that could not be done in any other medium — that of the actors knowing the audience is there and the audience collaborating with the company to create an ending.

| |

|

|

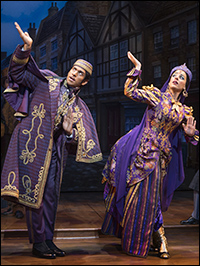

| Chita Rivera in the current revival. | ||

| Photo by Joan Marcus |

RH: The idea of a company of actors came to me when I first wrote my presentation for Joe Papp. The day before I met with him, I wrote at the top of the page "Victorian Vaudeville." And instantly all the fun and giddiness, and quirkiness of the framing device, poured out of me onto the page. I realized that I could take advantage of the fact that a music hall has a Chairman — to have him emcee, and to basically have him guide and corral the audience through the process. Then I remembered the convention of "Principal Boy" from English Christmas pantos, and thought, Edwin Drood surely, with his earnest nature and youthful energy, could be a perfect Principal Boy. And I realized how delightful it would be to have the first song sung by Jasper and Drood about being to Kinsmen, sung by a soprano and a baritone. Then have a love duet — "Oh my gosh!" I thought — for two sopranos, unheard of at that time. Princess Puffer could be played by the grand dame of the Music Hall Royale... All of this just poured out onto the page. I realized that when we stopped Dickens' story and acknowledged that he had written no more, the audience would still have endearing and engaging, lovable and funny performers to hold onto. That they wouldn't feel abandoned, but would feel like, "Now, let's get down to business together!" And they would already know these wonderful people.

Audiences are truly swept up in this production. I initially thought I would want to return just to see the various endings, but I want to get caught up in the entire experience again and again. It operates on so many levels.

RH: It's wonderful to have a revival that feels like we've just done it for the first time. I think the glorious thing about it is that it's a musical about putting on a musical. As much as the mystery element is all a lot of fun, when you do go Edwin Drood, you're going to a theatre to see a show about going to a theatre and what that relationship between actors and audiences has been for years.

One of that last numbers I wrote for the show was the opening number you hear now. I wrote that for Broadway, it was not in the Delacorte production. What happened was that Wilford Leach said to me, "The rap that we get whenever the Shakespeare Festival moves a show from the Delacorte to Broadway, is that people say, 'It was so much more fun in the park. It was so loose that it felt like a picnic. And now it's in this formal theatre, trapped by four walls and it's lost some of that vivaciousness.'" And I said, "Well, maybe I can write an opening number where the cast is in the audience and some of the people are up in the balcony — making the audience feel attended to." In showbiz history, opening numbers are "here we are," or "watch what we'll do," or "hey, look me over," or "let me entertain you," this opening number is all about, "Oh, my god! We have an audience!" It's an opening number paying homage to the fact that they are so grateful to the audience for being there. I think that [choreographer] Warren Carlyle, Scott Ellis and the cast launch that first number so earnestly and so energetically, that they make you feel like you are just the most important person in the world for them. That is always a little bit inherent in any show, but in this show, it's the major feature of it because you actually know you're going to have some say in what happens on stage. And that sort of sets the tone that's different from any other show I've ever done. I'm really happy to see it happening in such a robust way at Studio 54.

| |

|

|

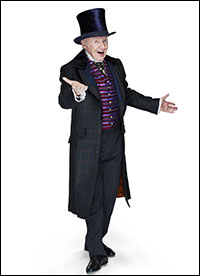

| Andy Karl and Jessie Mueller as the Landless twins | ||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

RH: After the very first preview at the Delacorte, it went wonderfully well and the audience was not only ecstatic, but felt that they had discovered something that was a big secret in New York. Joe Papp turned to me after the show was over and he said to me quietly, "Well, it works." And I looked at him in horror and said, "You mean you went this far with it and weren't sure if it would work?" First of all, I had incredible people to work with on that original production. I had [director] Wilford Leach and [choreographer] Graciela Daniele, and they were just as caught up in the intricacy of the machine and the giddiness of the game we were playing. They went with it and understood how we might make it work.

When we did the show in London, just having watched the show on Broadway, and because this show is the quintessance of theatre, in that it just wears its malleability on its sleeve, we had no hesitation of trying changes for London that we thought might be good... We made about eight major changes in the show. I wrote some new confessions, we removed a song called "Ceylon" from the score. In Central Park, we had two songs, we had "Ceylon" and "A British Subject." We lost "A British Subject" and used "Ceylon" for Broadway. I was never totally happy with that decision. When we went to London, we lost "Ceylon" and restored "A British Subject," which I think was a good thing, but I still missed part of that song.

So, for the new Broadway version I fused the two songs, so that you get the Landless twins talking about Ceylon, then you get my favorite moment of "Ceylon," which is Drood talking about his dream, and then we go into "A British Subject."

We also relocated "Off to the Races" — it used to be the second song in Act Two. I felt that the tone of the show deserved an upbeat rousing Music Hall ending for the first act. So, I created that little "Summing Up" moment where we have characters state their name and we sum up where the story now lies. I felt that was helpful for the audience. I also wrote a couple of new confessions. That version, became the version that Tams-Witmark licenses. So the American tour and all the versions that have been done since then have all been the London version.

Now, for this new Broadway version, I've made some changes again, and I took the old opening number at the Delacorte, which was "An English Music Hall," and I thought it might make a nice little Entr'acte for Act Two. I rewrote a lot of the lovers' exchanges for the new production, simply because I can do a lot more with comedy now, I have more license.

This will be the version that people will perform in the future. I think that director Scott Ellis has really helped me tweak and adjust it in a good way.

| |

|

|

| Stephanie J. Block in the title role | ||

| Photo by Joan Marcus |

RH: This production doesn't feel like a revival. From day one, because of Scott, the incredible cast, and my having re-orchestrated the whole show, it feels new. During rehearsals, like with any new show, I'm watching the cast, I'm hearing their voices, I'm seeing how they're playing things and I will write lines to adjust directly to that.

It was never of a period. It may have been on Broadway in the 1980s but it's not an '80s show. It is its own strange bird. I feel like this is a brand new show, like we are presenting this for the first time to the audience.

It's impressive and daunting that you not only took on the task of writing the book, music and lyrics, but also the orchestrations.

RH: When I was a pop songwriter, I heard arrangers taking my song and I would think, "Boy, they really didn't get it." And I thought, "Dear God, I'm going to have to learn to be an arranger to preserve my songs." So, I taught myself orchestration. I went to Manhattan School of Music, but I didn't learn anything specifically about pop-music orchestrating there. So, when Barbra Streisand asked me to do an album with her as a songwriter, I also was the arranger on that album and conducted the orchestra. And on all of my own albums, people don't realize that I had a pop record called "Him" with a big string section in it. They don't understand that there was a day where I sat and conducted that string part. They think I'm just singing the tune. I always did my own orchestrations.

| |

|

|

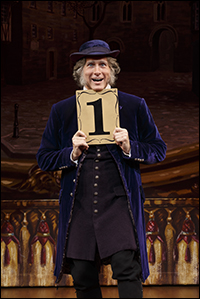

| Jim Norton as the Chairman | ||

| photo by Andrew Eccles |

When I was about a third of the way through the orchestrations, someone asked me at the Shakespeare Festival, who was going do to the orchestrations for the show? And I said, "I'm doing them." And they said, "You don't do that." And I said, "I don't? I dont know how not to do that. I know what the string parts are already." And so they said, "Well, good luck."

When I finished the initial Broadway orchestrations, I realized why that's not a good idea. I probably would never try to do it again. But then when I found out that we were going to have a different sized orchestra for this new version, I thought I would have to do them again because I know where everything is buried in the score, and I think I can get a similar sound to that which we had in 1985 out of this different instrumentation. So, it was a lot easier this time. I wasn't having to make every decision about what counter line I wanted to use, the challenge was to get it to sound full. Roundabout gave me, what is for today a more than decent-sized orchestra, 15 pieces — a lot of people consider that to be a luxury today. I think they sound really good. I think it sounds full and very orchestral and not like we're trying to make three synthesizers pass for a full Broadway pit.

| |

|

|

| Gregg Edelman | ||

| Photo by Joan Marcus |

RH: Any show at the Imperial Theatre in those years had to have an orchestra of 26 pieces. The producer couldn't come to you and say, "Could you please make it less?" It was the law. Those days are long gone except in rare occasions.

What's great about the Roundabout revival, the musicians aren't in the pit. They're right out in the room with you and that makes the brass very rich. We have someone who is playing piccolo, flute, oboe, clarinet, english horn, bass clarinet and two different kinds of saxophones all on one chair.

How did you go about writing this piece? Like you said before, it is so period, and all of it sounds cut from the same cloth. What were some of your first musical impulses?

RH: I wrote a hymn. The title of the hymn is referenced in the first chapter of the [Dickens] novel, called "When the Wicked Man." It's still in the score. You hear it in the underscore when John Jasper is first introduced at the beginning of the play. It's a solemn minor sort of funeral march. As well as the fanfare: anytime we go to Cloisterham, or we say "The Mystery of Edwin Drood" all together, there's that fanfare. I actually wrote most of the show in the order you hear it. The first complete song I wrote for the show was "A Man Could Go Quite Mad." That sort of minor xylophone machinery introduction became a leitmotif for the show. I was trying to write the show as if it were being written in a Gilbert and Sullivan world, but if Sullivan had the chance to travel to the future and hear some of the things harmonically that were going to be done by Puccini, by Ravel and by Holst. I thought I would allow myself a little more harmonic license and write a little more chromatically, but if I had written those initial pieces you hear like "A Man Could Go Quite Mad" and "Two Kinsmen," in particular, if I had written them in 1895, no one would think I had made a deal with the devil. I wouldn't have been burned at the stake for writing forbidden intervals.

| |

|

|

| Betsy Wolfe and Will Chase | ||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

RH: As far as "Moonfall" is concerned. I knew from the very start that I had a wonderful opportunity to have John Jasper present Rosa with a song that he had written for her birthday. And while it would be a song that would lie gracefully for a dewy and virginal soprano, lyrically, Jasper would betray his darkest desires for her. It would be his attempt to hear, if only once in his life, this love his life say precisely what he longed to hear her say. And it would also let us hear the kind of music Jasper writes when he thinks of Rosa. It was a great opportunity that allowed me to write a song that let us acknowledge a song is being sung. Usually, in a musical, characters burst into song to reveal their inner emotions. Here, a girl bursts into song because she's reading a song, and instead of revealing her emotions, she's revealing his emotions and reacting to what she is saying. I really wanted it to be both pristine and sensual. I delayed writing it. There was a space set aside for it. I moved past that moment in the show and wrote some other songs.

One day I came back to my office after lunch. And, believe me, I'm not saying anything supernatural is going on, but I sat down and played "Moonfall" almost exactly as you know hear it and almost without interruption. It's actually kind of intricate harmonically, in the bridge, chromatically, it's a toughie. But all of that came in one sitting. It really seemed to write itself. The trick for me, when I orchestrated it, I tried so hard to keep it pristine. If you look at the scores, they were all done in hand — there was no Finale software. If you look, it's the absolute neatest score in the entire piece. I just wanted it to be precise and without ragged edges. I think often when a writer or composer gets inspiration, and when it springs forth as if it had always been there, I think you've been working on it for years and finally, your subconscious allows your conscious to know the result of that work.