*

Although he already had two full-length plays running at Circle Rep, David Ives really arrived on the New York theatre scene in installments in the late '80s, sprinkling his witticisms around in the form of one-act plays at assorted festivals about town. When he gathered them up into a goofy six-pack on how we communicate and labeled it All in the Timing, it was "Open Sesame" to a long run.

That was 1993, this is 2013 — time for a 20th anniversary reprise of All in the Timing — so Ives' original sponsor, Primary Stages, is putting the show through the hoops again Jan. 23-March 17, in a new production directed by John Rando, the Urinetown Tony winner, and starring Eric Clem, Jenn Harris, Liv Rooth and a couple of rowdies fresh from Peter and the Starcatcher, Carson Elrod and Matthew Saldivar.

Two decades have taken author Ives in different directions — from Encores! key wordsmith to refried French farce to Nina Arianda, who won a Tony for Venus in Fur.

Here, he stops to reassess where he has been and where he is going. Can you believe you've reached this age where you're being revived?

No, I'm not being revived — not yet. The plays are certainly being revived — not that it's C.P.R. that we're doing on these plays.

It's been surprising fun to go back to these plays. I thought it might be hard because I haven't done anything like this where I've revisited something after this length of time — and something that was so special because, at the time, no theatre in town accepted All in the Timing except Primary Stages. It had been turned down by every theatre in town.

I want names.

You can name your own names. They all turned it down — saying it was "uncommercial," "it couldn't possibly succeed," "wouldn't ever find an audience" — and we ran for 606 performances.

Also, these plays are not the kind of thing I'm writing anymore. I sorta stopped writing short plays in any serious way years ago, so it's interesting to see what I was doing back then and what I had on my mind.

Each one of these little plays were a little education in some particular aspect of theatre. The Universal Language is about how far you can go with people speaking gibberish. Philip Glass Buys a Loaf of Bread — how much of a musical you can write in six minutes without having an orchestra. Each one of these was a challenge, and it's been nothing but fun revisiting them (knock wood).

The three chimpanzees trying to write Hamlet was called what?

Words, Words, Words. That was the first of the short plays that I wrote, actually — 1987, 26 years ago. And Sure Thing followed, and some of the others later on.

| |

|

|

| All in the Timing cast member Carson Elrod | ||

| Photo by Joseph Marzullo/WENN |

I know. I could partly write these plays because the Punch Line was there. They had that wonderful one-act comedy festival every year: three evenings of one-act comedies.

Did you migrate to Ensemble Studio Theatre, which is known for one-acts?

I did a few plays at EST, but the Punch Line really felt like my home, in a funny way.

I remember when I wrote Philip Glass Buys a Loaf of Bread — it was written entirely in rhythm and laid out on four columns on the page — so I was completely frightened that [Punch Line co-founder and artistic director] Steve Kaplan wouldn't do a play written in rhythm. I took it in rather trepidatiously and said, "Steve, I've got a new play." He took it out of my hands and said, "Philip Glass Buys a Loaf of Bread. I'll do it," and he put it in the "In" pile. It was as easy as that. It was only later on he realized he had accepted a play written in rhyme.

| |

|

|

| All in the Timing's Liv Rooth | ||

| photo by Joseph Marzullo/WENN |

Not only was it an anthology, it was one-act plays. Everybody said no one wanted to see an evening of one-act plays.

God, it's sure a lost art, isn't it?

It is a lost art because there's not much of a place to do it. That's why the Punch Line was so great. It was a great time for one-acts. I actually think the one-act play is a particularly rich medium for theatre because you don't have to fill 90 minutes or two hours. You can fundamentally do whatever you want, so the range of things that happen is much wider than it is in conventional two-hour plays. You don't have to adhere to reality quite so much. It almost encourages poetry in a certain way because one-act plays are so often made of one image or one particular happening that explodes for ten minutes, then stops. The intensity is all the greater because it's so short. It challenges a playwright's talent for compression, for making every word count, which is something I really like.

Two things from that show have stayed with me all these years. The first, from Variations on the Death of Trotsky, was the image of Trotsky going about his business, oblivious to the fact he has a mountain-climber's ax in his head.

Don't all of us have an ax in our head, and aren't we oblivious to it?

The other thing was Sure Thing. How many times has that happened? You're on a date, and you say the wrong thing, and you want a retake. In your play, a bell rings and the scene starts again. It's a totally inspired idea. I don't know why someone didn't do that before. It was always there. You just picked it up and ran with it.

There I was, the first ever.

I do know your style and interest in theatre has changed in terms of what you're writing now. It truly has matured. You could have gone through life Mr. Smart-Ass.

Yes. I got tired of having the word "clever" attached to my name. I actually dislike clever playwrights, so I didn't want to be one of those. Clever is interesting for a minute and then not, so I just thought of other things I wanted to explore. I felt like, "Yes. I could keep on writing smart-ass, one-act plays," but there were other things to be plumbed.

| |

|

|

| Director John Rando | ||

| Photo by Joseph Marzullo/WENN |

Well, luckily — or, unluckily, for me — I have never really wanted to do the same thing twice. Having done a whole bunch of one-act plays — I think I did several dozen of them, all in all, over the course of about ten years — every time I would sit down to write something and it was like something I had written before, I would put it aside. That, in itself, made me go off in different directions.

I also, at the same time, was starting to adapt for Encores! It was an education in theatre. It bent my mind in a totally different way.

As I got older, my attention was taken by, let's say, subjects that were less apt to look "clever" — like the excommunication of Spinoza [New Jerusalem] or, I don't know, pornographic sadomasochistic Austrian novels from 1870 [Venus in Fur]. You know, you get pushed off in various directions by things.

Were you pushed or pulled?

Well, that I can't say. It's always a mixture of various things that take you in directions, but I tend to write whatever is bothering me in some way at a particular time, and I often don't know what that thing is until the play is written and up and gone.

Did you ever see "Groundhog Day," the Bill Murray comedy where he's a TV weatherman caught in a time loop and keeps repeating the same day again and again?

Sure. It came out after Sure Thing.

| |

|

|

| All in the Timing's Jenn Harris | ||

| photo by Joseph Marzullo/WENN |

Not really. I think it was actually a bunch of those early plays that made him feel he and I thought in similar ways and had similar tastes and ideas. I think it was a combination of Sure Thing and Philip Glass Buys a Loaf of Bread and The Universal Language — all these things that were sorta touching on areas that he was interested in at the same time. I think it was more of a feeling of kinship than any particular play.

How did the two of you actually start collaborating?

He called me up one day and asked me if I wanted to come over for a drink and said he had something he wanted to talk about that was not important. I said, "Sure," so I went over to his house. We talked for an hour, and I finally said, "Well, Steve, what did you actually want to talk about? You said it wasn't important.'' He said, "Did I say it wasn't important?" I said, "Yes, you did," and he said, "Well, it actually is sort of important. I have an idea for a musical, and I wondered if you would like to work on it." I said, "Sure. What's the idea?" He told me the idea and then took out a manila envelope full of years of his notes on this idea. He said, "Why don't you read these notes? Take them home, and let's meet again if you're interested."

When was this?

I would say he called me up about a year and a half ago. We spent a good year just working out the book and the songs and the structure. You really have to storyboard a musical before you get to work on it, or you're going to waste your time. Once we had the structure and knew what the songs were, he started writing music.

I've read that he's done 20 or 30 minutes of music — and now he's on his second song? Is he writing out of sequence?

No, he's working in sequence. He said the other day he's going to play me the second number sometime soon.

And you've turned in the book?

Yeah, I would say last summer.

| |

|

|

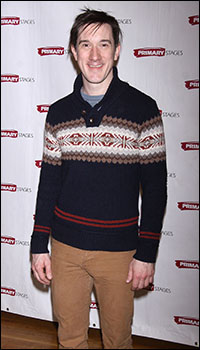

| All in the Timing's Matthew Saldivar | ||

| Photo by Joseph Marzullo/WENN |

I just did another French comedy called The Metromaniacs, adapted from a brilliant French comedy of 1738 that I don't think has ever been translated.

You read it in the original French? Are you used to doing that?

Yeah. That's how I work with all of these French plays. I always work straight from the French because I don't want somebody else's translation in my way. They're usually not very good, anyway.

I just always read the French over and over and over again, take a lot of notes. Usually, I spend a couple of months just taking notes and getting the structure right. Then, I sit down and start work on it.

Is that the only other language you work in?

Actually, my German is much better than my French.

Is that how you found Venus in Fur? I certainly read Venus in Fur in German — and read it a lot in German when I was working on that play, going back to the original — but the problem with German is that there are not a lot of plays in German that I would like to work on. The French have a whole raft of comedies that have never been translated, and I'm sort of exploring those. You know, your wit has upstaged your language skills. This is a side of you I didn't know about — and it's been going on all this time?

Yep. You can't just stand in the street and say, "I speak French."

Is there a parallel between your foreign-language translations and your Encores! musical adaptations?

Doing 33 "Encores!" has certainly helped doing these French plays. Since I'm working in verse, it's very close to working on a musical. The music of the language is very important, so I try to structure these French comedies pretty much like a musical. There'll be a variety song, there'll be a duet, there'll be a sort of choral conclusion to an act. Working for Encores! has been invaluable for working on French comedies.

Of the Encores! you've done, which ones are you proudest of, and why?

I would say Strike Up the Band, the 1927 George S. Kaufman show, with Kristin Chenoweth, Phil Bosco and Lynn Redgrave. I loved working on that. I loved working on Pardon My English, which was another Gershwin musical with a book by Morrie Ryskind. And Anyone Can Whistle, just because it was a famously troubled musical and I thought we all just did really good work on it.

Did you ever hear from Arthur Laurents about it?

Casey Nicholaw, who directed it, and I had to go over and talk to Arthur to sort of get his go-ahead to fiddle with the book — because it had to be cut down — just to ask him questions about what was in his mind when he wrote it and if he had any wisdom he could give us about the show. He was really very nice. He certainly didn't object to my version of it. I didn't talk to him after the show, but I heard he liked it.

Back to The Metromaniacs: what does the title mean?

Metromania is an addiction to poetry — to writing or reading poetry — and the metromaniacs is a bunch of people addicted to poetry in a country house, falling in love and mistaking identities. I had great, great fun writing it.

That's for the Shakespeare Theatre of Washington, where I've done two French comedies already. One was School for Lies, my version of The Misanthrope, and it got a great production here from Classic Stage with Hamish Linklater and Mamie Gummer, directed by Walter Bobbie. It is, by far, my best play.

| |

|

|

| All in the Timing's Eric Clem | ||

| photo by Joseph Marzullo/WENN |

Actually, I'm not a Moliere fan. I wanted to work on The Misanthrope because I never liked The Misanthrope. It always seemed like a comedy that Moliere left the comedy out of — or a tragedy that he never made tragic enough. I've never been satisfied by The Misanthrope, but I always thought it was a great idea for a comedy so I decided, basically, to fix what Moliere never got around to.

I also did for the Shakespeare Theatre of Washington The Liar, which is adapted from Pierre Corneille. It's going to be done here as a reading Feb. 11 by Red Bull Theatre, and there's a theatre that has been wanting to do it here for a couple of years. Finding the right personnel is part of the problem.

Last season I did a Jean-Francois Regnard play called The Heir Apparent, which had Carson Elrod in it, and he won a Washington acting award for it. He is, I think, one of our most brilliant comedians. I think he is as funny as anybody in New York right now or in this country right now. It amazes me that he's not a household word. In Heir Apparent, he was sublime. He played a servant who impersonates three different people — two men and one woman — and was extraordinary, right at the top of his game.

It's a delight to have him in All in the Timing. He also did A Flea in Her Ear up at Williamstown, directed by John Rando. He played the nephew with the speech impediment, and he stopped the show with it.

Those are the French plays that I've worked on. I do love working in verse because it's sort of an extra little challenge to compress language into iambic pentameter and use couplets, which is not usually fun but I try to make it as much "fun" as I can. What is the next new show of yours that will be opening here?

Well, I don't know. It depends on which theatre does which French classical comedy, I would say.

How many have you got lined up for New York?

Well, The Metromaniacs is for Shakespeare Theatre of Washington, but I have The Heir Apparent and The Liar waiting to come to New York, "coming to a theatre near you." I don't know when.

I wish you well with all of that. It's been interesting to grow old with you.