*

"What I am, Michael, is a 32 year-old, ugly, pockmarked Jew fairy, and if it takes me a little while to pull myself together, and if I smoke a little grass before I get up the nerve to show my face to the world, it's nobody's goddamned business but my own. And how are you this evening?"

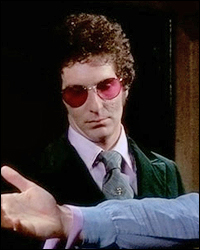

You had to hand it to Harold: He knew how to make an entrance — affecting a slow, serpentine slink while spewing venom at his mean-spirited host who'd just dressed him down for arriving stoned and unfashionably late for his own birthday party.

Hard as it is to imagine, if Harold — the haughty honoree among The Boys in the Band — has survived the AIDS crisis which would begin decimating the gay population a decade later, he would be 75 today — an unregenerate handful, replete with pockmarks and laser-like self-awareness — but the odds are, he didn't make it.

Leonard Frey, a brilliant and withering Harold on stage and screen, was the second of the original cast to die, a dozen days before his 50th birthday (8/24/88), preceded (6/3/84) by Robert LaTourneaux, 41, who played his dumb-hustler "birthday present," Cowboy. Two party guests — Donald (Frederick Combs, 57) and Larry (Keith Prentice, 52) — passed away eight days apart in September of 1992. The self-hating host, Michael (Kenneth Nelson, 63), was the last to go (10/7/93). Behind the footlights, fatalities included the play's original producer, Richard Barr at 71 (1/10/89) and, ahead of everybody, its original director, Robert Moore at 57 (5/10/84). All died from AIDS or AIDS-related diseases. Cliff Gorman — the show's Obie winner who played the most flamboyant character on the premises, the irrepressibly over-the-top Emory — succumbed to leukemia Sept. 5, 2002, at age 65.

|

||

| Leonard Frey in "The Boys in the Band." |

||

| photo courtesy National General Pictures |

These battle lines seem to materialize whenever the work is revived here — in 1996 at The WPA and Lortel, and in 2010 at a site-specific apartment near Chelsea.

A lot of human history stubbornly swirls above this groundbreaking piece, so it's no small blessing Crayton Robey has stepped up to the plate to produce and direct — ultimately, an act of preservation — a documentary feature on the play and film and on the people it touched, for better and for worse. It is called "Making the Boys," surfacing in New York City and Los Angeles movie theatres this month.

|

||

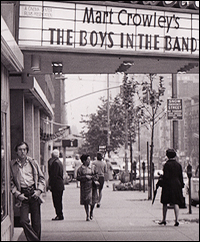

| Crowley outside a New York City movie theatre showing "The Boys in the Band." |

"I wanted this film to be celebrated and valued for what it meant to Americans at that time, giving a positive visibility about homosexuality. I think Americans need a piece like this to understand the journey of the homosexual and America itself."

Twenty or so "talking heads" have been corralled to give testimony about The Boys and the times — strong gay voices from a variety of professions: novelist Michael Cunningham, columnists Michael Musto, Patrick Pacheco and Dan Savage, actor Cheyenne Jackson, "Project Runway" designer Christian Siriano, songwriters Marc Shaiman and Scott Wittman, television host Andy Cohen and playwrights Paul Rudnick and Edward Albee.

Any desire for Crowley to chronicle "The Boys in the Band and How They Grew" in one medium or another has, he says, been quelled by this documentary. "I think the film did it. Crayton has done it all. He got lots of current people to cooperate with this. Good God, the leading playwrights of today and yesterday are represented!"

|

||

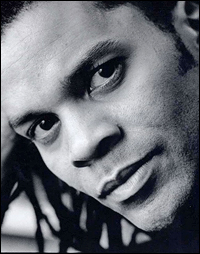

| Crayton Robey |

But these testimonials were not easily come by. Kramer, in his footage, seems quite winded and at half-mast. "I'm not sure what his health problems are, but I think it is quite well known that he had a liver transplant," Crowley volunteers. Robey nods in agreement. "He was recovering from something. What I loved was that when people participated in this, they really let me know that 'I can give you this amount of time,' [or] 'This has just happened with me, but I want to do this because it's important….'"

(Upbeat postscript: Kramer is looking much healthier these days. There's nothing like getting your play on Broadway to bring the bloom back to a boy's cheeks: His early-AIDS epic, The Normal Heart, opens in April at the Golden Theatre.)

The most conspicuous, and heroic, example of above-and-beyond commitment to the documentary came from Dominick Dunne, the novelist and Vanity Fair scribe who executive-produced the movie version of The Boys in the Band.

|

||

| Dominick Dunne |

Natalie Wood and Crowley crossed paths during the filming of "Splendor in the Grass," and she anointed him her personal assistant pretty much for life. She more or less supported him while he wrote The Boys in the Band, drawing from the life he knew well. "Not each character is literally based on someone," he points out. "I talk about Harold being based on my best friend. Of course, we had a very special relationship, and so I mentioned him. But most of the others were either people I had known other places in other times or they were conglomerates, people I had known like them. Emory is based on about three different men I have known."

Wood's husband, Robert Wagner, tapped Crowley to produce his "Hart to Hart" series when the playwright did not have a second hit. The Boys in the Band wound up running 1,001 performances and proved a pretty impossible act to follow.

Hollywood came calling for the screen rights to Boys, throwing all kinds of stars and cash at Crowley. "They were promising all the obvious names," he recalls, putting little stock in that fact. "It was like anything else. I sometimes wonder whether those stars had wanted to be involved or if they'd ever been sent a script."

It seems unlikely that big names would stay attached to a gay property very long back then. As late as the early '80s, it was considered career suicide — as Michael Ontkean and Harry Hamlin can attest for their "Making Love" (1982). Instead of stars, the film happily fell back on the original stage cast of nine — a ready-made ensemble with 1,001 nights to their credit. Given the unknown status of the players, the studio insisted on a better-known director than Moore and hired William Friedkin, right before he made "The French Connection."

Peter White, who played Michael's straight college pal who happens unhappily to stumble into the gay get-together, "was the last person cast in the film because Tab Hunter had been approached to do his role," says Robey.

White still acts, working the other coast in TV and film, "playing senatorial roles," says Crowley. The lone African-American in the cast, Reuben Greene, is believed alive but hasn't been seen since the '96 revival of The Boys in the Band. A call has gone out to him and to Gayle Gorman, Cliff's widow, to attend the premiere of "Making the Boys" March 7 at the TriBeCa Screening Room.

Laurence Luckinbill, the only other living cast member (he was the bisexual, pipe-smoking Hank), will attend with his wife, Lucie Arnaz, and another veteran from the original play, set and costume designer Peter Harvey.

One of the film's interviewees, Carson Kressley of "Queer Eye for the Straight Guy," will be rolling out the red carpet for the likes of Jujamcyn kingpin Jordan Roth, Crowley, Kramer and Griffin Dunne, Dominick's son.

"Making the Boys" begins its regular run in New York City at the Quad on March 11 and will open a week later in Los Angeles.