Overseeing the dazzling spectacle is Tony Award-winning scenic designer Christine Jones (American Idiot, Spring Awakening) in her inaugural role as director. Jones, who also created Theatre for One, a boundary-breaking intimate mobile theatre space designed for one performer and one audience member, is applying the concept on a much larger scale with Queen of the Night.

Playbill.com spoke with Jones about her work on Queen of the Night, which not only dissolves the boundaries between audience and performer, but re-invigorates what some might call "dinner theatre" as an immersive and emotional culinary ritual that plays on all of the audiences senses. The creative team reads like a who's who of the theatrical, fashion, culinary and design worlds, all of whom stepped out of their comfort zones to collaborate on the critically acclaimed event, which opened on Dec. 31, 2013, and has recently extended through June 1.

Queen of the Night is ambitious. Beyond creating a theatrical experience, you've challenged yourself with the oftentimes daunting task of serving food in the midst of the show. How did this entire experience come to life?

Christine Jones: It was Randy Weiner's idea in terms of the overall concept. Aby Rosen hired him, and before I was involved, Randy had the idea. Randy and I, actually, were having a meeting about something completely unrelated and he said, "Come down and see this space." So then I came down, and as Randy said, "This project is something that people self-select for." And he's right, I think once you see what's going on, you're drawn to it like a magnet.

Theatregoing audiences best know your work as a scenic designer, but you're also the creator of Theatre for One, which redefines the relationship and shatters boundaries between performer and audience. Was Queen of the Night a project that you thought would allow you to continue to explore that concept and bring about an opportunity to direct?

CJ: When I first started talking to Randy, I don't think we were sure exactly what my role would be; whether I would be designing or directing pieces, but the more we spoke, I said, "Who's directing this? I think maybe that's the role I can play here." [It fit] because of the very different experiences I've had working on many large-scale productions from the opera, to Broadway shows, and then working very intimately, I have a sense of both design and the overall experience of an event. I just kind of jumped in.

What were some of the initial inspirations for what the show would be?

Christine Jones: We had this very loose idea that it might be based on The Magic Flute, but the more we delved in, the more we kept asking ourselves, "What's the event? Why are people coming here? What's awesome here?" Then we started looking at initiation ceremonies and using the The Magic Flute as a parable of initiation rather than adhering to the specific narrative structure. What's also wonderful about the The Magic Flute is that it actually has a variety of musical forms and it in and of itself, is kind of this incredible hybrid. We started looking at Tamino and Pamina [the central lovers of The Magic Flute] as avatars for the audience and as they are initiated, we are also initiated, and that our descent into the basement of the Paramount Hotel signifies our descent into this underworld where anything can happen. We also looked at the myth of Demeter and Persephone when Persephone is taken into Hades and eats the pomegranate and becomes awakened. We used a lot of different themes of sexual awakenings, initiation and enlightenment. All of these things started swirling around in our heads. I was also looking at the Eleusinian mysteries, which were Pagan festivals that honored Demeter. And, again, they followed this structure of coming into a cave or an underground space and celebrating through ritual, dramatic reenactment and feast. The more we thought about that we realized we were creating a ritual for the audience to participate in. I think on a deep level we all kind of crave these kinds of transcendent experiences.

| |

|

|

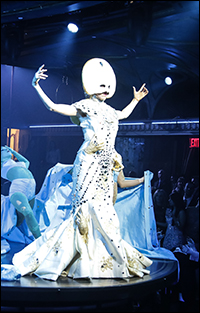

| Katherine Crockett in Queen of the Night. | ||

| Photo by Matteo Prandoni |

CJ: We had many, many meetings writing story outlines and gesture outlines and hiring writers and experimenting with different techniques. We did workshops with the actors and with the audiences. We did two workshops in the past summer. First we hired dancers, and then we felt like they needed to be actors, so then we hired actors for the workshops. When we went into auditions, we looked for performers who could move really well, but who were also just great human beings. So much of what happens in Queen of the Night is really about the interpersonal relationship between the performers and the audience. So much of what I think people experience in the evening is more of a communal event. By the end of the night, in so many instances, you've made friends with the people at your table, or you've made a strong connection with one of the performers. So we needed performers who were very open and warm and not afraid of intimacy and engagement on a level that is probably unlike most of what they had done in their other work.

Unlike standard theatre, where you watch a play from the comfort of your seat in a darkened theatre, Queen of the Night is very participatory. It asks for a sense of trust and openness from the audience. How did you develop that? Were you ever concerned that people might not go for it?

CJ: You know, on some level you feel like some people who come are inclined [to participate]. People come not having any idea what they're going to see. So right of the bat, somebody who buys a ticket will at least be open to the idea. But also the difference is that when we talk about audience participation, that often sends shivers up people's spines, because there's this sense of being put on the spot or publically embarrassed. But this kind of participation, I really think of it in terms of a mutual investment. It's what Theatre for One is built on. You equalize the relationship between the audience member and the performer and that equalization heightens the mutual dependence that each has upon the other. The performer gives the audience member the gift of their performance, and the audience member in turn gives them the gift of their attention and their presence. It's often like you said, you go to a lot of shows and you sit back and wait for something to prove to you that it's worth your time, that it's worth your attention and that it's worth your investment. But in this situation I think you're more aware of how necessary you are. Somebody looks you in the eye, somebody touches your shoulder and they say, "I'm here. Be here with me." And so, it's really an invitation. It's not this sudden thing that happens to you and you're pulled up on stage in front of everybody else. It's a warm invitation to experience performance, food and each other intimately and to engage intimately with all different aspects of the evening.

You and the creative team have conceived numerous private moments that are only witnessed by one audience member at a time, or sometimes, a small group. How did those come about?

CJ: It was a wide system of tools that we used to create them. We started with writing sketches of ideas; there were narrative elements and there were physical elements. We worked with a team of writers, but then we started doing improvisations with all of the performers. We brought in the 20 butlers and began to develop [moments]. They were invited to bring in their own inspiration and seeds of ideas, as well. I worked very, very closely with [associate director] Jenny Koons. Frankly, Jenny is a young director, but she's got way more experience in terms of actual directing than I do. I think everybody found a way to bring their strengths to bare. We would ask to see what an actor could do. Do they sing, do they move, or are they somebody who is really good with text? Then we asked them to do a lot of the development and creation and we distilled from there. And now, as the show is continuing, actors are still creating new moments.

| |

|

|

| A scene from Queen of the Night. | ||

| Photo by Matteo Prandoni |

CJ: There were just so many brains and we couldn't have done it without each and every one of them. From Jenny Koons, the associate director, to the stage manager, to Lorin [Latarro] and Matt [Steffens] the choreographers, who were interfacing what the performers' movement was from a choreography standpoint, but also how that interfaced with the kitchen. One minute choreography is referring to a count of eight before the actor does their next move, and then it's like, "Can you go get the lobster cage?" And then we had the restaurant staff involved as well. It was a lot of paperwork, a lot of trial and error, and just a lot of brains coming together.

Every single person was, in some way, working way outside of their comfort zone. Jennifer Rubell, the food artist, had never collaborated with other artists in this way before; never worked in theatre before. I'm not a director; I've spent most of my life as a designer. So I'm doing something that I don't normally do. Shana Carroll is accustomed to creating fabulous circus pieces, but within her own system [with Les 7 doigts de la main]. Everyone had to negotiate and hybridize with all of these other elements. We have a costume designer who is a fashion designer and a set designer who is a window designer. Everybody was doing something that they don’t normally do and we were all doing it with people that we had never done it with before. It was sort of a Herculean effort to develop a process together and to learn how this person works and that person works. I've worked on projects that have been difficult and sometimes they have been difficult for the wrong reasons. But this was difficult for all the right reasons. It was difficult because of the ambition of what we were trying to do. But it was just a tremendous group of people, very passionate, very committed, very excited by the challenge, and really warm, and I think as you can tell, this kind of work doesn't get made without really great hearts involved.

From the standpoint of a scenic designer, can you talk about the feeling that you want theatregoers to have when they walk in the door of the Diamond Horseshoe? Audiences immediately react to the physical space and to the architecture.

CJ: Actually, some of that work had begun before many of the creative team had came on board. There were architects already at work, there was [interior designer] Meg Sharp, and then Giovanna Batallia, who was overall the artistic-creative director. She just has incredible taste and is really known for a kind of exquisite sense of beauty. She brought on Douglas Little [the renowned window designer for Bergdorf Goodman] and he's dealing with things that you see really close up. The materials that he works with, butterfly wings and beetle shells, these are things that you don't see in most scenic designs. He then brought in people who dipped petals into wax to create the bathroom and those molded hands [on the doors]. There's just a level of detail that you don't often get to see in this type of material. I think, overall, there was a sense of deep profound beauty and [a drive to] take your breath away, and make it feel like you were walking into a dream or some kind of transcended space. Honestly, I don't know if this is appropriate to say, but I wanted people who have never been on drugs before to feel like they were having a drug trip. [Laughs.] Just how close to some hallucinatory experience can we create? How can we do that with architecture and light and materials and texture? And kudos to Aby Rosen for having the desire to bring this to life because I know other people have tried to do that. I think it was his commitment as a supporter of the arts and, who I’m told, likes a great party, for making it happen.

There is such an incredible array of participatory theatre in New York right now. What do you as a theatregoer and as an artist credit this phenomenon to?

CJ: I think that people want to fall in love and they want to feel. We all go to the theatre for some experience of connection or transcendence and I think that people are finding that here. I think people are in search of what they’re always in search of: I think people crave intimacy, and I think that they are finding it. There are so many different levels of that in Queen of the Night. It might be that you have an intimate engagement with food, or it might be with a beautiful design element or it might be with a performer, or it might be with the stranger that you met from your table. I think it’s the variety of opportunities for intimate engagement that is a big part of what's drawing people.

* Visit queenofthenightnyc.com.