*

Knickerbocker Holiday [Ghostlight 8-4450]

They don't write them, it is safe to say, like this anymore.

"This" refers to Kurt Weill and Maxwell Anderson's 1938 musical comedy Knickerbocker Holiday. A relatively lost musical, and not of the ignominious flop variety; while it wasn't a financial success, neither were most musicals of that late Depression year. It had a satisfactory run, and not an overlooked one in that it featured a legendary performance from Walter Huston (father of John and grandfather of Anjelica); an inventive production from a director who was to dominate the Broadway musical for 20 years, Josh Logan; and an all-time classic song hit, the enduring "September Song."

But Knickerbocker Holiday came before the day of the original cast album, and it lacked the "punch" that has resulted in revivals and recordings of other pre-Oklahoma! musicals like Anything Goes, Girl Crazy, The Boys from Syracuse and — of course — Show Boat. If you didn't catch Knickerbocker Holiday in its only full-scale revival, in 1971 starring Burt Lancaster at the Civic Light Opera in Los Angeles and San Francisco, you've likely never heard the full score with full orchestrations.

There was a concert reduction at Town Hall in 1977, starring Richard Kiley, and another as part of the York Theatre's Mufti Series in 2009. Those, until now, were the only mainstream appearances of Knickerbocker Holiday other than a few selections recorded on various Weill CDs. Not to mention a non-Weillesque 1944 Hollywood version, with interpolated songs along the lines of "Love Has Made This Such a Lovely Day" from Jule Styne and Sammy Cahn. I first heard Knickerbocker, years ago, by sitting down and plunking through the vocal score. What I found was thoroughly intriguing, with three songs — plus that old "September Song" — standing out: "Nowhere to Go but Up," "It Never Was You," and "How Can You Tell an American." These three still get to me; whenever I hear them, the melodies and rhythms stay with me for weeks thereafter, and I'm in precisely that state now.

| |

|

|

| Kurt Weill |

Until my birthday this past January, that is, when Knickerbocker Holiday came to Alice Tully Hall with a 27-piece orchestra, a full cast including more than a handful of musical comedy veterans, and an exploded chorus of 68 (as opposed to the 13 that Weill's original producers provided).

This from The Collegiate Chorale, a New York institution which two years earlier favored us with a full-sized concert version of Weill's Firebrand of Florence — which was, indeed, a long-lost flop despite the score Weill wrote with Ira Gershwin. While Firebrand was a treat, January's Knickerbocker Holiday was a revelation. Here was Weill and Maxwell Anderson's adaptation of Washington Irving's "A History of New York," with Weill providing cool colors and sly fun; this wedded to Anderson's sometimes tortured lyrics and heavy-handed attacks on the sitting President and his New Deal. (The bumbling New Amsterdam town council stands in for Roosevelt's cabinet, with the bumblingest member going by the name Roosevelt.)

The flaws of the piece were clear to see, and they in some ways explain why Knickerbocker Holiday never had a chance to become a member of the Anything Goes/Show Boat club referred to above. But the Collegiate concert gave audiences — and me — a once-in-60-years chance to hear what Weill's Knickerbocker Holiday, in actuality, sounds like. Which is to say, glorious.

Thanks to Ghostlight Records and a group of contributors who graciously saw fit to underwrite the costs, a live recording drawn from the two performances now makes it possible for one and all to hear Knickerbocker Holiday. And yes, it is as vibrant, bubbling, and unexpected as expected.

The big surprise for me is that the songs above cited — those I plunked out at the piano, and plucked out as favorites — are, indeed, the best of the score. With good singers and those 27 musicians, they sound bright and strong and refreshing.

"Nowhere to Go but Up" is one of those when-you're-on-rock-bottom-things-can-only-change-for-the-better songs, powerful and rambunctious. Weill casts it in the mode of a 1920s fox-trot, of all things; this is still the Weill of Berlin, three years after he arrived in New York. "How Can You Tell an American?" is another rouser with a driving rhythm, somewhat in the style of the "Kanonensong" ("Army Song") from Weill's 1928 Threepenny Opera. Anderson defines an American as "a person with a really fantastic and inexcusable aversion to taking orders, coupled with a complete abhorrence for governmental corruption — and an utter incapacity to do anything about it." Don't tell the Tea Party people, as they might try to adopt it as their theme song.

| |

|

|

| Kelli O'Hara performs Knickerbocker Holiday | ||

| photo by Joseph Marzullo/WENN |

Now, a listener could reasonably raise an eyebrow or three over Anderson's lyrics. "It never was you," goes that ballad, "No — it never was anywhere you." Never was anywhere you what? Anderson was a poet, with numerous verse plays to his credit; but that doesn't seem to translate to song lyrics. When he gets in rhyming trouble, he either fudges the issue or simply crosses his fingers and hopes nobody will notice.

There's a song, written in Habanera tempo, called "Sitting in Jail." Max sees fit to rhyme the title phrase with "they bring in your victuals in the well-known pail" — I guess he means dinner pail? — and "where they don't serve turtle and they don't serve quail." Which is a bit of a stretch. There's also an odd rumba duet for the lovers: "We are cut in twain," they complain, "and nat-ur-'lleeeee we bleed." (Maybe it's supposed to be funny?) Anderson goes so far as to try to rhyme "obligations" with "vivisection." Mr. Sondheim had no reason to discuss Knickerbocker Holiday in his "Finishing the Hat," but methinks it would have been ugly.

| |

|

|

| Victor Garber performs Knickerbocker Holiday | ||

| photo by Joseph Marzullo/WENN |

Now let's talk orchestrations for a moment. If you were working on a musical adaptation of an 1809 book set in Dutch New Amsterdam, circa 1647, what instruments would you use? Weill — in what might be his most delightful set of American orchestrations — builds the sound around sax and guitar. That's right; I don't suppose the Dutch burgers had saxophones, but they sure work deliciously well — and point up the fact that while the story was three hundred years old, the political connotations were from this morning's newspaper (circa 1938). Being a composer/orchestrator, Weill doesn't hesitate to include wild, delicious countermelodies.

Contributing to the joys of the CD are the leading players. Victor Garber is old man Stuyvesant, and presumably sings the role far better than Mr. Huston or Mr. Lancaster. (But what of Mr. Kiley?) Garber has just the right touch here as the mellow, peg-legged tyrant. Ben Davis, who has been a replacement in several Broadway musicals, is especially good in the main singing role of Brom Broeck. The similarly little-know Bryce Pinkham also does well as Washington Irving. Overshadowing them all is Kelli O'Hara, singing the relatively subsidiary role of Tina Tienhoven and shining all the way through.

There is also a bevy of featured clowns, including David Garrison, Brad Oscar, Brooks Ashmanskas, Steve Rosen, Orville Mendoza and Michael McCormick; none other than Garrison are prominent on the CD. Also on hand is Christopher Fitzgerald, battling steep obstacles. The small role he is playing (Tenpin) is here expanded, uncomfortably so, by adding a song ("Bachelor's Song") that was cut back in 1938 and for good reason.

The Collegiate Chorale's music director James Bagwell and the American Symphony Orchestra give a good reading of the score, and one that finally makes it come alive once more. The Alice Tully production was directed and co-adapted by Ted Sperling, who presumably contributed his Broadway musical knowhow to the proceedings.

Since I wholeheartedly recommend this recording, I'll skip the part of the review where I discuss the songs which for me don't work (sometimes in spectacular fashion). Get the CD of Knickerbocker Holiday. They don't write them like this anymore.

| |

|

|

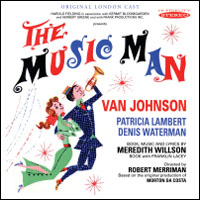

Sepia has brought us the 1961 original London cast recording of Meredith Willson's The Music Man. This is, for all practical purposes, a musical duplicate of the Broadway album, with a somewhat less intriguing pair of principals countered by a clearer and crisper sound from the orchestra pit. Listeners like myself who enjoy hearing something that is the same, but different, will want to get this second go round of the original New York version. What's more, Sepia gives us bonus tracks that open a whole new window on Meredith Willson's homespun classic.

The cast differences we can address quickly. Van Johnson, for sure, ain't Bob Preston; Johnson is capable, and I suppose was fine on stage. But after hearing Preston so many times, you can't help but notice that Johnson is nowhere near as spellbinding. The West End Marian, Patricia Lambert, has a different problem; she seems to be pretty good, but she of course isn't Barbara Cook — and that's an impossible obstacle to combat. (I've never come across a Cunegonde that I'd rather listen to than Barbara, or an Amalia or even a Liesl. And if you don't know her Liesl, get ye to The Gay Life.) But Ms. Lambert is perfectly fine.

The others have, not surprisingly, British accents; a little odd, especially when the quartet (here billed as "The Iowa Four") starts singing. Bernard Spear, who played the father of Jule Styne's Bar Mitzvah Boy and was Sancho opposite Joan Diener and Keith Michell in the West End Man of La Mancha, is Marcellus; Little Winthrop is Denis Waterman, who as an adult played Hildy in the 1982 "Front Page" musical, Windy City.

The band, led by Gareth Davies, does an especially fine job; the whole thing crackles, even if Van is something of a letdown. Johnson also demonstrates that you can sing Mairrian the Librairrian or Maaaahrian the Libraahrian, but it don't work if you sing Maaaahrian the Librairrian.

The highlights of this CD, oddly enough, are the nine bonus tracks. The first is unlike the others, but illustrative; here is Johnson singing "Trouble" six months before the London opening, presumably as an audition. And he is wonderful, with all the life and charisma that doesn't come across on the cast recording tracks. That is presumably Willson on the piano, tickling the keys, humming in diverse octaves, clacking, singing the chorus part, and tooting away like a toy trumpet with a built-in trombone slide. Then come a selection of demo recordings, with Willson singing and playing. As we all know — or most of us, anyway, know — The Music Man went through five years of development, with its neophyte author learning as he went along. One of these songs, "You Don't Have to Kiss Me Goodnight" — for the two teenaged lovers — made it to the 1957 tryout; the rest, though, were long gone by the time the show reached the stage.

The cuts are understandable, given our understanding of the finished Music Man, and these songs are not memorable. But unlike obscure cut songs from other musicals, these are all enlightening. For example, a lengthy number about Kentucky's "Blue Ridge Mountains," using the tune we know as "The Wells Fargo Wagon" set to the "Marian the Librarian" vamp; or the small-town paean to the big city, not "Gary, Indiana" but "I Want to Go to Chicago."

(Steven Suskin is author of the recently released updated and expanded Fourth Edition of "Show Tunes" as well as "The Sound of Broadway Music: A Book of Orchestrators and Orchestrations," "Second Act Trouble" and the "Opening Night on Broadway" books. He also pens Playbill.com's Book Shelf and DVD Shelf columns. He can be reached at [email protected].)

Visit PlaybillStore.com to view theatre-related recordings for sale.

Evan-Zimmerman-for-MurphyMade.jpg)