*

With yet another cast album of Stephen Sondheim's Follies coming along in November, this seems like high time to look back at the existing choices. How do they compare? In terms of cast? Material? Listening pleasure? I can, and shall, set forth to discuss this — knowing full well that each and every true Follies fan has his or her own set of opinions, answers, enthusiasms and peeves.

I eagerly obtained each Follies album when it first appeared, be it on LP or CD; in each case, I started listening almost before I tore through the cellophane. Four have thus far come along, beginning with the original 1971 Broadway cast album [Broadway Angel ZDM 7 64666] and followed by "Follies in Concert," a live recording drawn from two performances at Avery Fisher Hall in 1985; the original London cast album from 1987; and the 1998 Paper Mill Playhouse production. There have been numerous additional recordings of the songs, needless to say, but as non-cast recordings they do not enter into the discussion.

*

The original 1971 cast album of Follies [Broadway Angel ZDM 7 64666] has been maligned, again and again, for various sins; most harmful was the budgetary decision to restrict the show to one LP rather than two. Thus, room for only 56 minutes of song. (A complete recording of the score, as heard at the Winter Garden, would run roughly 90 minutes.) Follies opened to problematic notices in Boston and relatively weak advance interest in New York. The hot new shows at the time were Two by Two, a dismal musical boosted by the presence of old-time star Danny Kaye singing new songs by Richard Rodgers; and a revival of No, No, Nanette — which, like Follies, featured faded stars, most prominent among them Ruby Keeler and Patsy Kelly. Follies was, obviously, more artful than either and infinitely more important. That doesn't necessarily translate into ticket sales, and didn't. Capitol Records seems to have initially planned a double album for Follies, allowing room for the entire score. By the time the tryout began in Boston, economic prospects for the show — and thus the LP — were unfavorable, apparently convincing Capitol to cut their financial exposure. Capitol had always been a distant third in the cast album game. Columbia had its pick of shows, with sometimes stiff competition coming from RCA Victor. (Decca, the early leader in the field, had all but withdrawn in the mid-'50s.) Capitol, nevertheless, had two blockbusters on its list: The Music Man and that Streisandsical, Funny Girl. The label also had an existing relationship with the Follies producer, Hal Prince, having issued fine LPs of three successive Prince musicals: Fiorello!, Tenderloin and Sondheim's own A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum.

But the cast album game had become treacherous for Capitol following Funny Girl in 1964. With Columbia and RCA capable of offering better terms (including in some cases large investments), Capitol was relegated to lesser choices. The label's last big push came in the 1968-69 season, when it made poor-selling recordings of three failures: Celebration, Canterbury Tales, and Prince's own Zorba. That was the end for Capitol on Broadway, or it seems to have been intended as such; they were to ultimately make one last attempt, with Follies.

|

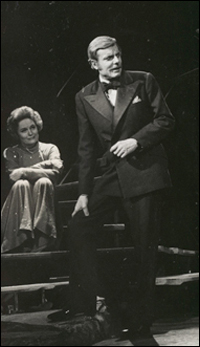

||

| Alexis Smith and John McMartin in Follies. |

Thus, the original Broadway cast album was recorded — on April 11 — with a stopwatch running furiously. Most of the songs were represented, with four wholly excised: "Rain on the Roof," the instrumental "Bolero d'Amour," "Loveland" and "One More Kiss." (The latter was recorded that Sunday, though not included on the LP.) There were also any number of trims and interior cuts, which only exacerbated the situation. What's more, the recording is marred by technical flaws; Capitol did not have the high tech facilities of Columbia or RCA, and it is apparent. (For more information on this — and more information on all things Follies — see Ted Chapin's "Everything Was Possible," which is no doubt already on your bookshelf. (Or should be.)

Discussions of the cast albums of Follies inevitably start with complaints about Capitol and disparagement of the 1971 album. But as every new Follies recording comes along, I listen to it for a while and then file it away in the back row. The 1971 Follies, be it truncated and flawed, remains the Follies of choice for me. These might not be the best individual performances among the several albums, and it certainly does not demonstrate the best fidelity — aurally and textually — of the four. But the first original cast album is, for me, Follies.

This brings to mind, in a way, Sondheim's revered Porgy and Bess. The Gershwins' folk opera — more properly "the George Gershwin/DuBose Heyward folk opera" — opened in October 1935 and closed three months later. The composer died in the summer of 1937. In 1940, Decca took a group of original cast members including Todd (Porgy) Duncan and Anne (Bess) Brown into the studio — along with original conductor Alexander Smallens — to record eight songs. When Porgy was successfully revived on Broadway in 1942, six additional numbers were recorded; all this before the so-called "original cast era" began with Oklahoma! in 1943.

These 14 Decca tracks were primitively recorded, trimmed to fit on 78 RPM discs, and represent only 46 minutes of the full-length opera. Porgy has been subsequently produced and recorded again and again and again, usually spearheaded by conductors who insist that their version — finally — realizes Gershwin's true intentions. Some of these recordings are very good, sure; but I contend that the Decca set — not an original cast album, technically — is the closest we'll ever get to what Porgy sounded like when George was standing at the back of the theatre. And the closest to what he, and DuBose and Ira, intended.

I have a somewhat similar view of Follies, albeit for different reasons. I am not wedded to the original cast performances because they are perfect, or because the 1971 album represents the finest production of Follies that e'er I've seen. Because they aren't, and it ain't necessarily so. Those first performances, though, are authentic. Follies, it can be said, is a reunion of ghosts — living ghosts. Most of the older players in 1971 were, so far as Broadway was concerned, ghosts; with one main exception, none had been in the spotlight — any spotlight — for a decade or two (or more). And most of the veterans had lived through the same "good times and bum times" as the characters; they didn't have to search Wikipedia to look up Windsor & Wally, William Beebe's bathysphere and Brenda Frazier.

If ever a Follies with a perfect cast comes along, I might well switch to the resulting recording. (As long as the original orchestrations by Jonathan Tunick are present, that is, in full strength.) But that hasn't yet happened, and for various reasons seems unlikely.

|

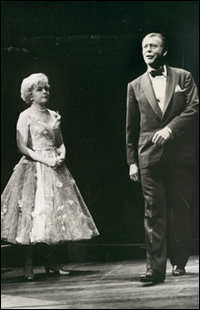

||

| Dorothy Collins and Gene Nelson in the original Broadway production |

"How was Follies?" you ask a friend who has just seen a performance somewhere. I contend that the answer usually depends on the collective strengths of not only the central quartet but these three ladies.

Now, I have never seen a wholly compelling central quartet — and mind you, I've seen plenty of productions of Follies. To paraphrase the Master, "when you've been through Vivian Blaine and Bob Aw-aw-awl-da, everything else is a laugh." (That's Robert Alda, the one-time Sky Masterson; Tappan Zee Playhouse, July 1973, with the only intriguing spot being Lillian Roth's "Broadway Baby.") The original 1971 cast — and the original cast album — includes the finest Sally imaginable, in the person of Dorothy Collins. Her two big numbers, "In Buddy's Eyes" and "Losing My Mind," have never been equaled. Alexis Smith, who like Collins was making her Broadway debut, is a fine Phyllis and does especially well with "Could I Leave You?" (One of the imbalances of Follies is that while all four leads get two showy solos, Sally and Ben also have two major duets. Phyllis and odd-man-out Buddy don't.)

|

||

| Danny Burstein in the current revival |

||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

The actresses in the three critical supporting roles were unforgettable. Yvonne De Carlo — who, like Nelson, seemed slightly over her head — gave a compelling performance of the tour de force, "I'm Still Here." (Sondheim wrote this song — a replacement, during the Boston tryout — specifically to suit De Carlo's capabilities.) The other two ladies were even better. Ethel Shutta had been on Broadway in 1922, actually starring for Ziegfeld opposite Eddie Cantor in the 1929 hit Whoopee!; she was also a popular singer with the band of her husband, George Olsen. Many people have sung "Broadway Baby" over the years, but I don't think anyone has ever been out there "walking off her tired feet" like the 74-year-old Shutta. (I type Shutta, but it's not pronounced "shut-ta"; it's more like "shuh-tay.") Ethel was matched by Mary McCarty as the lady who glances in the mirror and wonders "Who's That Woman." If you happen to have access to a copy of "Theatre World 1948-1949," turn to page 141. Compare that bright and sprightly comedienne from Sleepy Hollow — what, you don't remember Sleepy Hollow, the Ichabod Crane musical? — with the Mary McCarty of Follies and Chicago (where she created the role of the Matron). That page 141 photo is presumably what she glimpsed in the mirror when she slayed the house with "Who's That Woman."

|

||

| Cover art for Follies in Concert |

|

||

| Barbara Cook |

||

| photo by Mike Martin |

The three featured ladies at the Philharmonic help save the day. Those of you who have never heard this recording can surely imagine what Elaine Stritch does with "Broadway Baby." (She still sings the song today, just about every time she comes before an audience, but her 1985 rendition seems more genuine and is worth seeking out.) I would certainly not compare her to Shutta, who sings the song like it's her autobiography, but Stritch is tasty and gives this Follies a boost. So does Phyllis Newman, with a crisp "Who's That Woman." Due to the stellar nature of the Philharmonic cast, Newman has what might be one of the more interesting groups of backup singers in show biz history — including Cook, Remick, Stritch and Betty Comden (who teamed with Adolph Green to play the Whitmans, singers of "Rain on the Roof"). The third of the subsidiary roles was played by the biggest star on the stage that night, by far: Carol Burnett. Audiences today don't quite realize how popular she was in those days, courtesy of her long-running TV show. Burnett — in 1985 — was arguably bigger than Liz, bigger than Liza. Here she sings "I'm Still Here" and brings down the house.

Listening to the Philharmonic Follies once again, for the purpose of this column, I am struck by how remarkably good Cook is. Hearing her, augmented by Stritch and Newman, I couldn't help wondering why I hid this recording in such deep storage that I don't suppose I'd have ever listened to it again if I weren't writing this column. Then came Mandy's two songs, and I remembered precisely why I deep-sixed "Follies in Concert." I found these two tracks unlistenable then, and unlistenable now; not the actor's fault, exactly, as I'm sure that he would have come up with something suitable and special if he were actually playing the role.

This 2-CD set includes a bonus that is required listening for true Sondheim fans: the soundtrack recording of "Stavisky," the score for the 1974 Alain Resnais film. This is 45 delectable minutes falling mid-way, musically, between Follies and A Little Night Music, with a distinct flavor of Ravel. (This was surely Sondheim's intent, the effect magnified by Tunick's luscious orchestration.) Fans of cut Follies songs will immediately identify "Bring on the Girls" and "Who Could Be Blue?" Next week: Recordings of the Cameron Mackintosh London production of Follies and Paper Mill Playhouse's revival, which features studio recordings of songs cut from the score.

(Steven Suskin is author of the recently released updated and expanded Fourth Edition of "Show Tunes" as well as "The Sound of Broadway Music: A Book of Orchestrators and Orchestrations," "Second Act Trouble" and the "Opening Night on Broadway" books. He also pens Playbill.com's Book Shelf and DVD Shelf columns. He can be reached at [email protected].)

Visit PlaybillStore.com to view theatre-related recordings for sale.