*

"I have tapes of myself starting out," said the composer Gunnar Madsen. "I think any musician has. They should never be released."

True enough. But if Madsen had had a father like Austin Wiggin, perhaps we would have heard those tapes. Austin was the father of three New Hampshire daughters — Dot, Helen and Betty — whom he hectored into forming a rock band. The curious result was the 1960s oddity known as The Shaggs, which put out a single album titled, portentously, "Philosophy of the World." Made up of 12 tracks of discordant, tuneless, hectic strangeness, it sank like a stone. But the group, and the album, have had an odd afterlife. In 1980, at the urging of Terry Adams and Tom Ardolino, of the band NRBQ, it was rereleased on the Rounder Records label. Rolling Stone magazine, perversely fascinated, called it the comeback of the year. Since then, the Shaggs have been the three-piece train wreck from which the music industry can't seem to avert their gaze. The band has been praised as a prime example of "outsider music" and primitive art by the likes of Frank Zappa, Kurt Cobain and music critic Lester Bangs. In 1999, RCA released the album and gave the Shaggs even wider exposure. Lengthy profiles of the Wiggin family's odd achievement were published in the Wall Street Journal and The New Yorker.

That's when playwright Joy Gregory first became aware of The Shaggs. The group is the subject of a musical, also called The Shaggs, written by Gregory, Madsen and John Langs, now playing at Playwrights Horizons.

A few weeks after reading the Wall Street Journal and New Yorker articles, Gregory was listening to the radio when a bizarre racket began to emanate from the speaker. "The Journal article started with a lot of people trying to describe the music," she said. "Based on those descriptions, I knew what I was listening to." It was The Shaggs, three teenage girls who knew next to nothing about how to play the two guitars and drum kit that their father had given them.

| |

|

|

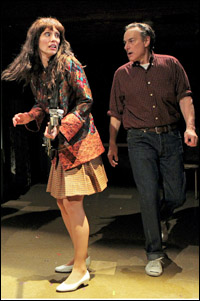

| Jamey Hood and Peter Friedman in The Shaggs. | ||

| photo by Joseph Marzullo/WENN |

Madsen had a similar reaction. He had been aware of "Philosophy" since 1980, but didn't listen to it until Gregory — whom he met at a 1999 playwright-composer workshop — suggested the story of The Shaggs might make a good musical.

"There's just a very deep sadness" in the music, he said. He admitted that he probably sensed that sorrow partly because he'd read the articles about the Wiggin family beforehand. Austin Wiggin was a strong disciplinarian obsessed with his mother's prediction that his daughters would become a popular music act. To make the prophecy come true, he took his children out of school so that they might spend every day practicing. He then secured them a weekly gig at the local town hall, and a contract with a tiny local record label. "It was forced out of these people," said Madsen. "They didn't have a burning desire to make this music. It was almost concentration-camp music, squeezed out of people."

| |

|

|

| Emily Walton and Peter Friedman in The Shaggs. | ||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

Gregory had recently finished writing a play on Charlotte Bronte, from which she drew unexpected inspiration. "I made some connections between the Wiggin and the Bronte sisters," she explained. Both families had three sisters, who lived in a rural world, and were dominated by an overbearing father. The Bronte sisters' father "was just an oppressive force. He was so frightening to the sisters, they started creating verse in secret. I connected that to the shame impulse of the Wiggin sisters, that they were removed from outside influence. Their father forced them to leave school. There was a similar, isolated urge to express their lives. The Wiggins and Brontes both felt like they were creating their own art from outside of society."

One important question the creators had to contend with was: how do you write a musical about characters who are not musical? How do you write tunes for the tone deaf? "That was an exciting dichotomy," admitted Gregory. "I thought, what would they have had hoped they would sound like?," said Madsen. "They hoped they would please their father. And for Austin, I think his dream was an end of financial woes and some respect for his family." The resulting score is a mix of internal, tuneful monologues — by the sisters and their parents; painfully accurate recreations of Shaggs tunes; and idealized renditions of the same songs.

Knowing that he was writing a show about living individuals caused Madsen some discomfort. (Austin died in 1975, after which his daughters rarely picked up their instruments. Austin's widow, Annie, died in 2005, and Helen the year after. But Dot and Betty still live near their hometown of Fremont, New Hampshire.) "I have to say it's been an awkward experience writing about actual people, and people who didn't choose to be in the spotlight," said the composer. "It's been touchy. I just want to make sure I do right by them."

| |

|

|

| Sarah Sokolovic, Kevin Cahoon and Jamey Hood in The Shaggs. | ||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

"We don't know if one daughter was rebellious and one was trying to please Dad," said Madsen. "We were trying to tell a story that made sense to us."

But what sense can an average theatregoer make of a story as surreal and singular as that of The Shaggs? "It's beyond American," theorizes Madsen. "It's pretty universal to have a drive, to feel a bit left out and want to belong. It's not a bad thing to strive for. I love that. What I love about Austin is his passion and his drive. But for him, he didn't have a feedback loop on whether his plan was working or not."

From a certain perspective, one could argue that Austin Wiggin's plan worked very well indeed. The Shaggs' music, after all, is still being listened to and discussed, more than 40 years after it was made. Asked if he agreed with the critics that claimed The Shaggs' music displayed some brute artistry, Madsen paused. After struggling a few moments, searching for a diplomatic response, he finally said, "No."

"That's not what I hear, and I have spent a lot of time with it," he added. "It's really just a beginning of trying to make music. I made the same mistakes when I was just starting out. Melodies that go up and down. Words that are scrambled together. But they were recorded. They were engraved for life as beginners."