*

Hunter Foster, the boyishly handsome actor who has distinguished himself in plays (the Kennedy Center's Mister Roberts), plays with music (Million Dollar Quartet) and musicals (Urinetown, The Producers, Grease and — earning a 2004 Tony nomination — Little Shop of Horrors) nurtures another theatrical passion when he's not auditioning, rehearsing or performing. As anyone who saw Off-Broadway's Summer of '42 knows, he's a librettist — that underappreciated job of scriptwriter for musicals. You know, the bits that don't sing. He's got another musical, Bonnie & Clyde: A Folktale, in the can, in anticipation of a world premiere in Georgia in 2012. Foster is currently in Arlington, VA, shaping The Hollow, his new musical version of Washington Irving's early 19th-century story "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow," with music and lyrics by Matt Conner. Signature Theatre is producing it in repertory with another musical, The Boy Detective Fails, as part of a commission initiative called the American Musical Voices Project: Next Generation World Premiere Repertory Series. Foster spoke by phone in between rehearsals on Aug. 24, the day after a 5.8 magnitude earthquake hit Virginia.

I love following new work and I've always wanted to talk to you about your writing. The first preview of The Hollow was yesterday?

Hunter Foster: The first preview was yesterday. It was quite an eventful day, as you could imagine. We were in rehearsal and then we had to evacuate the theatre. We actually lost about an hour-and-a-half of rehearsal time because of the earthquake. But I thought, all things considered, last night actually went pretty well for the first preview.

| |

|

|

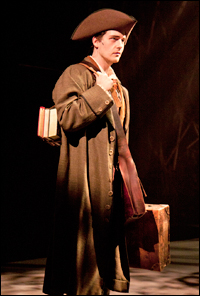

| Sam Ludwig in The Hollow. | ||

| photo by Scott Suchman |

HF: I was actually next door at the Harris Teeter [grocery store] and I was at the salad bar just getting some soup — we were on a break — and the salad bar just started moving back and forth. I thought someone was moving the salad bar. I was like, "That's weird. Why would anyone be moving the salad bar — why is the salad bar moving?" And, I looked up and things were falling off the shelves and the whole place was just swaying back and forth. It was just crazy. And when I went back to the theatre, the cast and crew were all coming out of the theatre. We have these overhanging trees in the show, and the director said he looked up and the trees started to swing back and forth. That's probably the most dangerous place you can be — at a theatre — with all the instruments and things that are hanging. So they quickly got everyone out of the theatre. It was pretty difficult, but luckily we got the show off last night, and people ventured out and came to see it, so it was good. It's based on "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow." What's your take? Is it a "traditional" approach borrowing directly from the story?

HF: Well, Eric Schaeffer, who's the artistic director here [at Signature Theatre], came to us about two years ago and said he wanted to do a musical version of "Legend of Sleepy Hollow." I think there was a Broadway production like 30 years ago that ran for, like, six performances, and I think it was a pretty literal production. We wanted to do something that was a little less literal, so we thought, "What if we did it as an allegory?"

Without giving too much away, I think that as opposed to literally taking the novel and musicalizing it, we wanted to do something a little bit deeper. It's definitely a book musical with Ichabod Crane and Katrina Van Tassel and Brom Van Brunt — all the characters from the novel, but I always like putting contemporary themes into something. What if we did "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow," but we are telling more of a story about what's happening today? It's like The Crucible. When Arthur Miller did The Crucible, he was writing a play about the Salem witch trials, or the witch hunts, but he was making a statement about McCarthyism. I think that's what intrigued me about doing this. It's definitely a traditional [book] musical, but the Headless Horseman, in a lot of ways, symbolizes something. Especially in a post-9/11 world, we've been living in a fearful society. Whether it's the news media, or evangelists, or the Tea Party, they kind of create this fear in our society. And so we thought [there was] the correlation of fear and this Headless Horseman, who kind of terrorizes this town. People are afraid of this thing that's coming around and attacking people. We kind of thought that there was a parallel between the Headless Horseman who attacks people, in the same way that Pat Robertson said that hurricanes are sent by God to destroy New Orleans.

It sounds like you're underlining what was in the Washington Irving story, in a great way: It's about a liberal school teacher from Connecticut — from New England, where liberalism began in the U.S. — coming in with new ideas that scare some of the conservatvies in town, right?

HF: Different people will come in and have different ideas of what they think it is, and I'm starting to see there are definitely some political overtones. The town kind of wants to stay in one place and the Dutch colonies back then were like that — isolated from the rest of the country and kept to themselves. Even Irving says in the novel — I can't remember the exact quote — but he says that Sleepy Hollow has stayed the same while the world outside kind of continues forward. Sleepy Hollow wants to remain the same, it doesn't want to move forward, and so then he introduces a character that wants to take them forward, and [we see] their resistance to that — and this [resulting] fear.

Fear motivates people. If you put the issue of same-sex marriage on an Ohio voter's ballot, you will get more voters running to the booths to protect a tradition and reject the unknown "other."

HF: That's right. Exactly right. And I think it seems more prevalent in our society now than it ever has been. The media, which creates fear — even the earthquake yesterday, you would have thought… it was scary, but you know, we had what, a crack in the Washington monument and a few dishes falling over? But, you would have thought, watching the news, that it was Haiti. They blow everything out of proportion and they're saying things like, "bigger aftershocks," which there could be, or this could be a "foreshock," but they perpetuate fear. Everything seems so fear-based in our society, and I think that's what brought us to telling the story in this way. It's kind of a reflection on how we think society is today.

| |

|

|

| Whitney Bashor in The Hollow. | ||

| photo by Scott Suchman |

HF: Well, it was Eric Schaeffer, like I said, and Matt Conner, who wrote the music and lyrics. [Matt] received a grant from the New Voices Project, which is down here. I was in Kiss of the Spider Woman down here as an actor, and Eric [knew that] I'd written a couple of shows, Summer of '42 and Bonnie & Clyde, and he was like, "Do you want to write with Matt?" We sat down and Eric said, "I've always wanted to do 'Sleepy Hollow,' as a musical." Matt and I…thought, "Yeah, it would be great to do a horror musical," and do it in a way that was different from how the other horror musicals had been done.

Give me a sense of the feel of the music. Is it atmospheric? Is it...creepy?

HF: I think it's both. Matt writes very… he's a mood writer. I would say that in the opening number, I can hear the leaves, I can hear fall, I can hear everything that Sleepy Hollow represents. You can hear the leaves falling. You can hear the wind. Everything he writes, it just feels very atmospheric. I think the whole show kind of feels that way. I thought he was definitely the right person to write a show like this because he can just capture the mood and the tone: From the first note you know exactly where you are, and that's not always easy. His music is definitely almost another character in the show I think.

How did you guys write together? Did you write the bones of the script and give it to him? Did you write it as a play first and then dissect it together?

HF: You know, we talked about it. You go back and forth, writing an outline, and try to figure out what's the best way to tell the story. We had the source material, obviously. And, there's sort of pitfalls in that original source material because some of the characters can be two-dimensional and caricatures, especially the steady schoolmaster — and Brom Van Brunt could be the "Gaston" figure [from Beauty and the Beast]. And, Katrina can be a "Belle." The characters could easily go in a certain direction, and we wanted to go away from that and make them more real, each with their own problems and issues. So, we just started with taking the novel and figuring out a way to tell the story. We just kind of fleshed out the story and did outline after outline after outline. We did the workshop two years ago. The great thing about Matt is that Matt is inspired to write music. He doesn't necessarily wait for me to come up with a plot point. If he is inspired to write something, he writes it, and then it either works for the show or it doesn't. What's so great is that almost all the material he wrote on inspiration is in the show.

Did the source material pose challenges?

HF: There's not a lot that happens, dramatically, in the novel that warrants putting that story right on stage, so we had to kind of come up with our own story, and find the love story between Katrina and Ichabod.

It's still a triangle between Ichabod, Katrina and Brom?

HF: It is definitely a triangle. It's definitely a love triangle. I assume that your Ichabod is not some caricature, but he is a genuine guy — a leading man.

HF: What's interesting is, the guy that we cast as Ichabod [Sam Ludwig] and the guy that we cast as Brom [Evan Casey] are very similar, so we thought they were like flip sides of the same coin.

How aware of the old Disney musical cartoon version are you?

HF: I love the Disney cartoon. [Laughs.] It's one of my favorite things. We love it. Matt and I both love the Disney cartoon.

Did you watch it together?

HF: Well, there's a couple numbers in it that we watched on YouTube just to amuse ourselves. I haven't seen the whole thing in a long time. It's just my favorite thing in the world. I remember as a kid loving that cartoon. It's Bing Crosby, narrating, I think.

Yeah, it is. I remember it has some some storytelling scene in it, where shadows are moving across the wall. It was kind of terrifying.

HF: Yeah it was.

How do you address the famous chase scene that we all know so well from various film versions, where Ichabod is chased on horseback by the Headless Horseman?

HF: Unless you got the horses from War Horse at Lincoln Center, it's hard to recreate a lot of that stuff theatrically. I hope that by the time we've gotten to the end of the play, that we've gone on such a different journey that you won't even think about what we know of the ride of Ichabod Crane.

| |

|

|

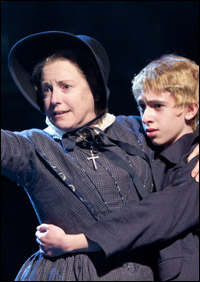

| Sherri L. Edelen and Noah Chiet in The Hollow. | ||

| photo by Scott Suchman |

HF: No, I would definitely say that the very end of the show is straight from the novel — the very end of the show. It is addressed. It's just addressed in a different way.

I'm curious to know how long you've harbored the goal of writing. I certainly know Summer of '42 and I know there's a Bonnie & Clyde out there. Did you write as a kid? Did you want to do this for a while?

HF: Well, you know, it was actually the first thing I ever did. My parents weren't theatrically inclined. I didn't know anything about plays when I was a kid. It wasn't until much later that I knew what Broadway was. But when I was in third grade, I wrote a play, and it was four pages long and it was based on "Dracula," and I actually played the lead role of Dracula. I had rehearsals, we performed it in front of a class, and I don't even know what the inspiration for me to do that was. I would say that was the beginning of not only my writing career, but my acting career because I not only wrote the play, but I starred in it. [Laughs.] My original goal, when I was younger, I wanted to write novels. That's what I wanted to do. I wanted to go to school for creative writing and I wanted to be a novelist, and then I got into acting, and I really loved acting very much, so that kind of became my focal point for a long time. Once I got comfortable in a place that I could start writing and felt confident, that's when I wrote Summer of '42, and started to work on Bonnie & Clyde, and now The Hollow. I wish I had more time. I've been fortunate that I've been working as an actor, so there's not always time to write.

When you're in rehearsal for a play, as a writer, is it a different kind of nervous than as an actor, or are you more Zen about it? What's your approach?

HF: It's much worse as a writer. I'm kind of a control freak. As an actor, I feel like I'm in control. I control my performance. I control everything that I do. And, as a writer, you sit there and you go, "There's nothing I can do. I can't do anything." You're helpless. [Laughs.] Once a performance starts, there's literally nothing you can do. If they screw up or something happens, you are just at the mercy of the theatre gods, I guess, and that's really hard to let go of, for me. It makes me more nervous. Last night, I was really nervous and I'll be nervous again tonight. I'll be nervous until we open.

I assume that in the rehearsal room it might be hard for you to just sit there and listen.

HF: It does drive me a little crazy. I have a hard time sitting in rehearsal and not doing anything. It's just I'm so used to being involved, and I'm sure that I drive my director crazy. I always just want to jump up… I never want to direct. It's something I never, ever want to do. But it's weird to be in a rehearsal room and not be actively involved. That's the hardest part for me.

And does it drive you crazy if and when lines are not spoken in the way you had imagined them?

HF: Coming as an actor, I know what the process is. I know some writers are very stuck on how things should be said or written or done. I know, as an actor, I want things to sound natural to me, so I ask, "Can I say it like this?" Some writers are resistant to it, but as far as I'm concerned, as long as we're telling the story, if you want to change something and do it in a way that makes it more comfortable, I'm all for that. That's the actor in me. I'm always thinking of the actor first.

Do you have a drawer full of other ideas? Do you have non-musical plays that you are interested in writing?

HF: It's funny you say that. My wife [Jen Cody] and I, we work at the Cape Playhouse, which is in Dennis, MA. We go there every summer. She's up there right now doing one. I've always wanted to write a farce. Farces are very similar to musicals in a lot of ways. Farces are closer to musicals than just regular plays, just because of the heightened [emotions], so I had this idea to write one, with the idea that we could do it at the Cape. We could do it next summer. I'm actually working on it.

You'll be in it?

HF: I don't know. I am definitely writing a part for my wife and some other friends of mine that we perform with every year. If there's a part for me, yeah. [Laughs.]

Kenneth Jones is managing editor of Playbill.com. Follow him on Twitter @PlaybillKenneth.