*

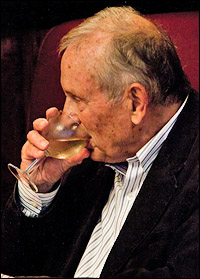

A.R. Gurney, Jr. would like to have a drink. But he can't. He enters Sardi's second floor bar with a big box under his arms. It's filled with opening night presents for the cast of his latest play, Office Hours, which was opening at the Flea Theatre Off-Broadway the night we met.

"That looks gooood," he said, his eyes clapping on his interviewer's cocktail. "Is that a dry Martini? That looks delicious. But they hit me too hard and tonight's going to be a long night."

There's little drinking in Office Hours, a play which draws on Gurney's long pre-theatre career as a teacher at MIT. But, generally speaking, his characters know their way around a jigger. One of his most famous titles, after all, is The Cocktail Hour. His namesake, A.R. Gurney, Sr., never saw that production. Which is probably a good thing.

"My father was nervous what I was going to say about the family," recalled Gurney. "I wrote that play, really, about him. He was dead by then. I never could have written that play while he was alive. It would have hurt him too much." Gurney, Sr. could be a tough man to impress. He didn't approve of his son's intention to become a writer. He saw some of his early plays, but, said Jr., "he didn't like them much. This is an old joke. My first well-received play in Manhattan was in 1971, at Lincoln Center, called Scenes From American Life. I said to my father, 'Come on down and see it.' He said, 'If it's any good, it will come to Buffalo.' "

| |

|

|

| A.R. Gurney, Jr. | ||

| photo by Krissie Fullerton |

Office Hours is inspired by an entirely different chapter in Gurney's life. Unlike most of today's playwrights, Gurney, freshly 80, had a full professional life well before he decided to become a full-time dramatist. "I taught at MIT for 26 years. It was the great experience of my life, teaching. I got tenure. MIT was so good to me. I said, 'I'm going to try my hand more seriously at playwriting.' They said, 'Well, we'll keep you on the books. Can we list your course every year?' I said, sure. I left in 1984. Finally, in '96 they said, 'Maybe you better retire.' "

Office Hours is the sixth Gurney play produced by the tiny Flea Theatre in downtown's TriBeCa district. His Flea plays have been of a markedly different stripe than those performed at Lincoln Center Theater, Primary Stages, Manhattan Theatre Club and other Uptown institutions. They are primarily political and, while George Bush was in office, they adopted his administration as their primary target. Now that Bush is out, and Barack Obama in, the politically left-leaning Gurney has less to complain about. But he's still got plenty of opinions.

"I'm a big Obama guy. He's a very civil guy. He's trying to do the right thing. But he's poltically a little naive, I think. The health care bill is terrific, what he's trying to do. But it doesn't kick in for a few years, and as a result, all people know is they are spending a little more on insurance companies, and they blame Obama for that. I think he should have waited a little while before he did that. There are other things. He should have gotten us out of this war." (About soon-to-be-defeated Republican New York gubernatorial candidate Carl Paladino, he had less charitable things to say.)

|

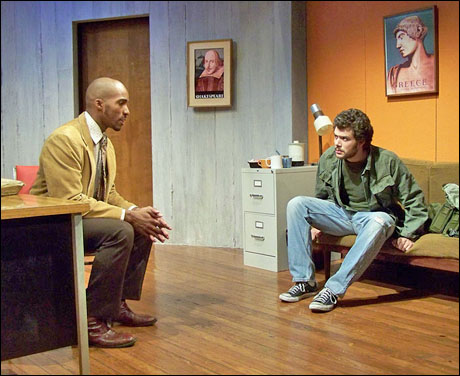

| Bjorn DuPaty and Raul Sigmund Julia in Office Hours |

| photo by Max Ruby |

| |

|

|

| A.R. Gurney, Jr. | ||

| photo by Krissie Fullerton |

Cornell, a grand dame of her day, is little remembered today. (Interestingly, Gurney said Cherry Jones is the contemporary actress who comes closest to her acting style.) But, she's a trifle better known now thanks to The Grand Manner. Soon after its debut, somebody posted a short clip from "Stage Door Canteen" — the only film Cornell ever appeared in — on YouTube. "The film is pretty terrible," commented Gurney. "She's the only one who really takes off."

In the scene, Cornell is handing out oranges to the soldiers coming through the mess line at the Stage Door Canteen, a famous social hall in Time Square during World War II, where Broadway actors served and entertained members of the armed forces. One young soldier recognizes Cornell and mentions his acting coach told him "If we've never seen you in Romeo and Juliet, we've never lived." (Cornell did a famous Juliet on Broadway in 1934.) The soldier begins the balcony scene from the Shakespeare tragedy, and Cornell picks it up. "And she is terrific," remarked Gurney. "She must have been 40 when she did that, but you get a sense of the kind of acting she did."

| |

|

|

| A.R. Gurney, Jr. | ||

| photo by Krissie Fullerton |

One question before he leaves — his name is Albert R. Gurney, Jr., but everyone calls him "Pete." Why? "I can't explain it. I'm a junior. My father was called Bert. I have an uncle called Al. So, I think my mother, I don't why — maybe she knew someone she liked named Peter — but she just called me Peter. And it became an issue, because most people outside Buffalo called me Pete. And anybody who knew me at all in Buffalo called me Peter." Perhaps realizing this doesn't clear up the mystery of his nickname much, he adds, "There are other people who use Peter as a nickname."

Really? Who?

He laughs. "I can't think of any."

(Robert Simonson is a special correspondent for Playbill.com whose work is also seen in the pages of Playbill magazine. His most recent book, "The Gentleman Press Agent," was published by Applause Books in June. Write him at rsimonson@playbill.com.)