*

Certainly there have been rock musicals since the show that is arguably the first rock musical, Hair, debuted more than 40 years ago, but far fewer than musical musicals. So the standouts are easier to pluck out. What's more, some of the choices are so obvious, you can't err too much in compiling the list. If you're going to talk top rock musicals of all time, you pretty much have to include Hair, which started everything. Ditto, Rent, which revived the category a quarter century later.

Now, let's be clear what we mean by "top." This is not a list of the best rock musicals. That's an entirely subjective matter and up to personal taste and one's own critical standards. By "top" we mean important, historically significant, influential—or, in the corporate-speak, sport-oriented parlance of the day: game-changers. After each of these five shows came along, all that came after was either subtly or dramatically different.

The five shows were decided by the Playbill.com staff. However, to buttress the selections, we asked a variety of artists variously connected to the rock musical genre to kick in their two cents as to why these productions were so remarkable. Some of them—such as Stephen Trask and Michael Mayer—were actually part of the creation of a couple of the shows in question. Others—Marc Shaiman, Stew, Diane Paulus—are fellow artists and appreciators.

| |

|

|

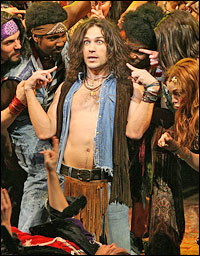

| Will Swenson and Tribe in the 2009 Broadway revival of Hair. | ||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

"Hair was as unlikely a project as could be envisioned," recalls Merle Debuskey, Papp's press agent, who witnessed the growth of the show. "Its creative parts were disparate, all unknowns in the greater theatre community. The instigators, Ragni and Rado, were East Villagers and familiar with the evolving young culture—societal as well as the performing arts. LaMama-ers. And there was Joseph Papp who always had his nose in the air sniffing at the new scents in the theatre."

"To me, Hair broke all the rules about the bourgeoise experience," said Diane Paulus, who directed the recent hit, Tony Award-winning Broadway revival of the show. "It took the counter culture and put it on Broadway. It's often defined as the first rock musical. I think what's so extraordinary about Hair is it was truly a reflection of the time and culture and what was going on on the street. Often in the theatre, the popular culture is reflected back, but it's looking back five or ten years. Hair was immediate."

| |

|

|

| Caissie Levy, Sasha Allen and Kacie Sheik in 2009's Hair. | ||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

Marc Shaiman, composer of Hairspray, also found the best of both worlds—theatre and music—in the show. "Hair was and is, simply, the original and still the best—theatrically innovative—even while going backwards to an almost vaudevillian style of performance—and featuring the most thrilling score imaginable. No wonder it was the last Broadway musical to get multiple songs on the radio." Added Stephen Trask, composer of Hedwig and the Angry Inch, "Hair is amazing. It's more than the enthusiasm of the cast carrying the show. There's witty language and great melodies. It's not just an accident and of its era."

| |

|

|

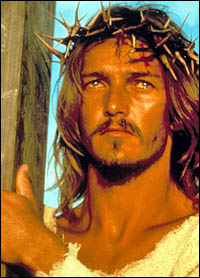

| Ted Neeley in the film "Jesus Christ Superstar." | ||

| photo courtesy Universal Pictures |

Lloyd Webber and Rice were also canny marketers. The show was an album before it was a production, making the show a legend before it was a reality. Rebellion had been packaged and sold. "JCS was already a titanically successful album," recalled Merle Debuskey, who ran the press for the Broadway premiere. "The decision was to fashion a stage musical out of the album. When they did and produced it, it was preceded by a huge audience awareness and interest."

The strategy worked. "JCS was the album (yes, album) that completely blew my 11-year-old mind," said Shaiman, "and made me want to write my own Biblical rock musical, which started and ended with my attempt to put words in God's mouth about the Garden of Eden. I gave up after four lines. If he had only written just this score, Andrew Lloyd Webber would always be, to me, a genius."

"I love that show," said Paulus. "It's the music. I don't have a production experience of that show. It's the energy of the music. It gets in your blood, and it gets your blood rolling. It takes a sacred subject and tears it up. It's the greatest story of all time and nothing's sacred." The idea of "Nothing Sacred" became one of the main tenets of the best rock musicals to come.

| |

|

|

| Anthony Rapp and Adam Pascal in Rent. | ||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

"I think there was just something gritty and raw about it," said Jon Hartmere, librettist of bare: A Pop Opera, who was influenced by Rent. "It seemed like there might be a place for something like bare after seeing it. The reference points I had for musicals before Rent were shows like Phantom, Miss Saigon, Les Miz...all shows I enjoyed, but they weren't singing about current-event issues. So I think it just opened up avenues for what a Broadway musical could be, at least from the perspective of someone starting out at that time."

| |

|

|

| Idina Menzel and Fredi Walker in Rent. | ||

| photo by Carol Rosegg |

The composers of Hair had failed to forge prolonged careers after that show and Andrew Lloyd Webber grew more and more operatic, and less rock-oriented, after Jesus Christ Superstar. Larson—even though he had tragically died before his show opened—became a new beacon for young composers. Following Rent, the theatre wouldn't forget about the rock musical for another quarter century—it couldn't, since the show ran for 12 years on Broadway. More entries in the genre followed at a regular clip.

| |

|

|

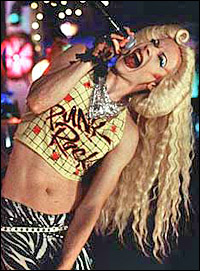

| John Cameron Mitchell in Hedwig's film version. | ||

| photo courtesy New Line Productions |

"Hedwig and the Angry Inch contains some of the best songs ever written — songs that transcend a 'rock musical' label," said Damon Intrabartolo, composer of bare. "Stephen's adherence to form and structure are awe-inspiring. Every melody is so perfectly constructed and catchy and his lyrics are so original and moving—they have raised the bar ridiculously high for the rest of us! The songs are incredible in the context of the show and have such strength on their own, outside of the theatrical context. That show has no peer; there's Hedwig, then there's everything else."

But Hedwig's music was also innovative because it was performed as rock 'n' roll. Every rock musical before Hedwig had used certain aesthetic aspects of the concert arena in its presentation. Hedwig drew no distinction: The story took place during the course of a rock concert, and the songs were sung by Mitchell into a microphone with a back-up band, in the former ballroom of an old hotel in Greenwich Village. If you had told the audience they were attending a concert, and not a show, many would have accepted the idea. This concert concept would come to dominate the rock musical genre in the coming years.

"There was a commitment on the part of the creators to hold on to our musical aesthetic no matter how hard it was," recalled Trask. "In musicals, everything must serve the story and compromises must be made, and very often those compromises seem to be made at the expense of good writing. It was hard for us to find the music that we wanted to present at the same time that we served the piece theatrically. There was a full story told, but it worked as both concert and monologue at the same time."

Trask thought he and Mitchell "showed a way of merging rock music with a show by changing the relationship between the book and the songs, so that the songs might relate thematatically to the material that's going on in the book, without this sort of seemless approach that was perfected by Sondheim, where the book and songs go in and out of each other. The songs didn't necessarily have to continue the monologue. You could do the songs in the most natural way as opposed to musicalizing them. We made a decision [about] the way the songs relate to the book. You can see in Spring Awakening and Passing Strange that relationship of the book." "It's very much about performance," said Paulus of the musical. "That show shares a lot with Hair. It's like a happening."

| |

|

|

| Skylar Astin (top) and John Gallagher Jr. in the Tony Award-winning Best Musical, Spring Awakening. | ||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

"When we were working on it," remembers director Michael Mayer, "one of the issues was the songs didn't function in the way conventional musicals were meant to. They weren't really forwarding the plot. They were articulated as coming from character. That was intentional. When I hit upon the idea of setting the play in its original period and letting the songs be contemporary, the disconnect was intentional, knowing that a musical theatre audience was going to put them together." While not naming shows, Mayer says he sees the influence of Spring Awakening in many other productions since the musical premiered.

Trask sees something in Spring Awakening that can be said of all the shows on this list: a lack of concern with scenic opulence or specificity. "They use very small gestures of a single prop and a lighting change," said Trask.

And, of course, Sheik provided another great score. It may seem like an incredibly obvious point, but rock musicals—emphasizing as they do a musical idiom born outside the theatre, a world of singles and albums and musicians and concerts and screaming fans—draw most of their inspiration and identity from the music itself.

"What makes a great rock musical?" asked Paulus. "Great music! Incredible music! Whatever you want to say about Hair, it's great music. And that's the truth about Jesus Christ Superstar, that's the truth about Duncan Sheik's music. This is music that millions of people respond to on a bigger level than a musical."

That makes five, and five are all we picked. You, gentle reader, would have possibly (nay, very likely) picked a different five. No need to stew in your own opinions. Let them be known! Share your thoughts with us at rsimonson@playbill.com and we'll print some of your responses in our PlayBlog.