*

Gold, 34, who was raised in Westchester and New York City and is a product of the directing program at the Juilliard School, is currently represented on Broadway as director of Theresa Rebeck's Seminar, a comedy about hungry fiction writers, and Off-Broadway as director of the clutter-and-violence-filled revival of John Osborne's Look Back in Anger, a portrait of working-class frustration. He is an associate artist with Roundabout Theatre Company, which is producing Look Back (now to April 8) at the Laura Pels Theatre.

Most of us had never heard the name Sam Gold five years ago, and now he seems to be everywhere, gathering credits at major American theatres including The Old Globe, Manhattan Theatre Club, Williamstown Theatre Festival, Lincoln Center Theater, Yale Rep. You might say his rise is meteoric.

Gold is now in rehearsal for the New York City premiere of Dan LeFranc's The Big Meal at Playwrights Horizons, where he previously scored a hit with Anne Baker's Circle Mirror Transformation, and where he staged Bathsheba Doran's Kin..

We spoke with Gold about his passion for Look Back in Anger and his interest in new and old plays. This is my first experience with Look Back in Anger, though I know its reputation, certainly. I had expected something incredibly specific to post-war British men and the lost generation of '50s men, somehow, and I found it to be really timeless and universal — much more than I though it would be.

Sam Gold: That's great. That's definitely what my interest was, so I'm glad that came across.

What was your experience with the play before this?

SG: It's a play that I've known and loved since I started in the theatre. It was a play that, as a student, I read and got me really excited, and it's probably one of the few plays that I'd say sent me into being interested in the theatre. You know, I started like everybody — as an actor — and I think it was a play that, as a young actor, it just felt like an exciting world to be in. I really loved the play when I was a young actor, and it stayed with me ever since. I've always found it to be an extremely challenging play — a play that I think would be very exciting and challenging to try to figure out a way to make a larger audience connect to it to the degree that I connected to it.

It's not a "well-made play," and it's a very rebellious play, so I think those are things that I was interested in, especially as a younger person. I am finding myself now with a lot of interest in finding ways to connect plays like that — that are challenging and bold and rebellious and, you know, voices that are taking risks. Trying to connect those plays to contemporary audiences is something I feel really excited about.

|

||

| Sarah Goldberg and Matthew Rhys in Look Back in Anger. |

||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

SG: Yeah, I was much more interested in the sort of "love rectangle," as I call it, in young marriage and the ways in which, you know, people are abusive towards each other as their relationship is falling apart. And, I was also very, very interested in the class war that is going on in the play. And the class war is specific to the '50s in England, but I wanted to try to bring out the sort of universality of that. The class issues and the class anger and the ways in which it is complicated through this relationship is something I thought could really be interesting for people now to look at.

Right now is the time where class is in the national conversation — sort of in the largest way since I've been alive. We are in the midst of class war, and the idea that class war is something in the national dialogue is very helpful to how you could understand and watch this play. So, it certainly wasn't why I did the play. I didn't say to myself, "Oh, I want to explore post-collapse American class conflicts." What I really wanted to explore was a beautiful play that I've always loved and the spirit of that play and all the complicated, messy, emotional, political mess that Osborne tapped into.

Whether he even knew it or not at the time, he sort of hit a nerve and dug into something that really is about something large and something that people really connected with. They connected with it both by loving it and by hating it. The play was sort of despised at the time it was written. I found it very interesting to do a play that had had such a divided response.

|

||

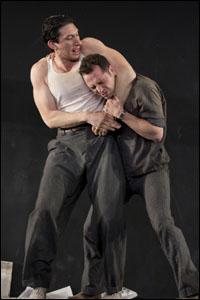

| Adam Driver and Matthew Rhys |

||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

SG: Yeah, I think the writing is beautiful. I love the language of the play, and I find that it's very challenging because I think in the 50s, people wrote more poetically and spoke more poetically. What was, at that time, a piece of "kitchen-sink realism" had dialogue that was so poetic. We identify a kind of kitchen-sink realism with a much less poetic way of speaking. So, those are interesting things to sort of explore in the play.

I guess one man's poetry is another person's crudeness. What surprised you about the play as you dug into it? Did you have an "A-ha" moment — an angle that you didn't see before?

SG: The thing that was always really challenging for me as a young American was understanding what the stakes were for an upper-class woman and a working-class man in post-war England. I think, for me, basically when people speak with British accents, I think they're fancy. Jimmy Porter is very articulate and he quotes Shakespeare and Dante, he's very well read. It's very hard, I think, to enter into the class issues of the play as someone unfamiliar with that time and place. And, for me, the "A-ha" moment was trying to find, for myself, an analogous way into that class conflict. I started thinking to myself, "If this play took place in the American South in the '50s and Jimmy was black and Allison was the daughter of the plantation owner, what would be the stakes of those two people getting married and him stealing her away from her family and living in a crappy apartment somewhere?" You think, "Well, the Ku Klux Klan might try to kill them." It's very high stakes. I found a lot of "A-ha" moments as I tried to explore the stakes of that class conflict within the marriage.

The play also seems to sort of pre-figure Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? in a really interesting way — in terms of its word-play and its arrested-child fantasy stuff. Did you find that?

SG: Yeah, I think the play has a really nice place within the history of dramatic literature. I think it's part Hamlet, part Streetcar Named Desire and gave birth to Harold Pinter and Edward Albee. He sits in a really interesting place in the history of drama. I think for people who go to see theatre with a sense of history, it's really a great pleasure to get to look at it historically, and I wish for people to go to see plays with that kind of context. Like, when people go to a museum and see a Picasso, they understand that the way he draws the eyes on the face is in the context or the history that he's rebelling against, and you sort of understand the history of art as you look at it.

|

||

| Matthew Rhys and Charlotte Parry |

||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

SG: Exactly. I mean, to be really literal, the apartment that Jimmy and Allison live in has no running water; they have to go downstairs to get water, so there would not have been a kitchen sink. I think that's just a broader term for a kind of working class, realistic play. [The genre does] a good job showing you the small living spaces [characters] live in — showing them very realistically, so people in the audience, who, mostly, were middle-class people, could see how the working class lived. That was an important new development in the theatre. I think, now, the sort of middle-class audiences that go to see plays are pretty used to seeing that. And, literally, are they in an attic?

SG: Yeah, the location for the play is the attic of a Victorian in a midlands town in England: big houses in an industrial town in England where they rent out the attic as if it's an apartment. There was no bathroom. You'd have to go downstairs to use the bathroom. They were very poor and they were not living in very good conditions.

|

||

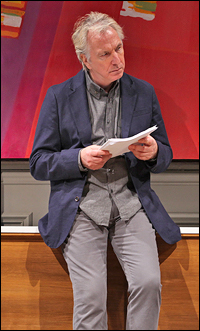

| Alan Rickman in Seminar. |

||

| Photo by Jeremy Daniel |

SG: Yeah. You know, a sort of major decision for me was sort of trying to connect to some of the original spirit of the play. When the play was first produced, it was very shocking to the audience — the physical production. In England, at the time, there really wasn't the portrayal of working-class people on stage, and Osborne was really angry about that and really wrote this play as a way to try to put working-class people on stage and to see his class be represented on stage. With America, we had had Clifford Odets and Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams — we had had a history of the working class being represented in the theatre, but England hadn't made that change yet. It was very shocking when Osborne wrote this play and the lights came up on an upper-class woman and an ironing board in a working-class flat. It was very shocking to people, and people got very angry. I thought, "Well, how can I complicate that event?" And, one way is to not do kitchen-sink realism. We're very used to, right now, seeing plays in working-class apartments. Most plays that are written in America in 2012 take place in somebody's crappy apartment, and I decided it would actually be more shocking to not show the apartment at all. We don't really use any of the theatre [stage] space in this production. I thought that would be a good way to let the audience know that we're going to have an experience with this play that was supposed to be a different way of looking at a play — that history was very interested in that kind of difference. I'm familiar with your work on new American plays such as Kin, We Live Here and Circle Mirror Transformation. Do you like juggling new and classic titles? Do you want to do it all?

SG: Yeah, I really do. But, I think, you know, my career has been very focused on brand-new plays for a while. But, always, the reason I got into the theatre was because I was inspired by these classics. I was an English major and I loved the plays, so I think my work with new writers has always been based on my information from these old plays, and I've always wanted to get to do productions of them. I find it very exciting to approach these old plays having spent so much time on brand-new productions. It makes me a little less, I think, worried about faithfulness to the original production because I've done original productions. I find it very easy to relinquish my sort of respect or need to listen to the original productions of older plays because I understand that the original productions were responding to the audience directly in front of them, and I'm so used to responding to the audience directly in front of me. I'm very interested in making things for a contemporary audience and not particularly interested in museum pieces or looking at old plays in the context they were originally done. So, I really like the challenge of bringing old plays to new audiences.

|

||

| Reed Birney and Deirdre O'Connell in Circle Mirror Transformation. |

||

| photo by Joan Marcus |

SG: It very much depends on the writer. I mean, really what I'm there to do is help bring the writer's vision to the stage, so if the writer seems like it helps them to have another voice very vocal in the room, I tend to be very vocal. I like very much working on plays from their infancy, where I can sort of shepherd them to production because I think I do better the more involved I am. I am just able to do a more specific, more detailed job the earlier I get involved, so I pretty much like being a dramaturg. I like being involved in the writer's process, but I also am very respectful of the writer's process and like to take it on a case-by-case scenario — what will be most useful to them. I assume sometimes you just take an assignment, as well? You have to put a show up.

SG: Yeah, I rarely take a job like that. I want to be intrinsic to it, and I want to be needed, and I like to take risks and work on things where I'm needed. I don't tend to take a job where I just put up a finished script. The closest I'd ever say I came to that was doing Annie Baker's play The Aliens, which she wrote and didn't show anyone until it was in really great shape, and I got a draft that basically didn't change from the draft I read to production. But Annie and I have a very close collaboration and worked together a lot, so I still felt like we were really making something together, and I felt very inside the organic process — it just happened to be a process where the words didn't really change very much because she had really done such a beautiful job on the draft that there was no work that needed to be done.

Can you give an example of a play that you were with from the ground floor?

SG: Annie's other play that I did, Circle Mirror Transformation, she handed that play to me when there were 30 pages, and we worked on that play from then until there was a first draft, and then we did four workshops of it over two years before we were even in production, so I was very involved in all stages of it.

You were part of the Juilliard directing program.

SG: I was the last director in that program before it, unfortunately, shut down. I very much hope that they'll be able to bring that program back because it was a great program. What was the most important thing you got out of it?

SG: The relationships I made. I met so many great young actors, who were so hungry and so talented and who I've worked with so much since then. And, also, wonderful writers who I've collaborated with since our time at Juilliard. My role in the program was mostly classical work. There was a wonderful playwriting program at Juilliard, so I met a lot of writers just through the cross-pollination of our program and I went on to working with a lot of those writers, mostly just based on seeing each other's work and admiring each other's work and getting to know each other.

(Kenneth Jones is managing editor of Playbill.com. Follow him on Twitter @PlaybillKenneth.)